Eames Lounge Chair. Photo by Herman Miller

Eames Lounge Chair. Photo by Herman Miller

Husband and wife design team Charles and Ray Eames were two of the most influential designers in the twentieth century and their pieces still inspire people today

From short films on spinning tops to military stretchers, textiles and interiors, the Eameses had a prolific and wide reaching career. Known for their iconic chairs, their aim was to design affordable, stylish furniture that could be mass produced and would therefore be highly accessible to the American people.

The look of their pieces was modern, functional and sophisticated. There was also a sense of play in their design, Ray’s subtle contribution, and a familiar comfort. Their most famous chair – the highly popular Eames Lounge Chair – was an interpretation of a well-worn baseball mitt. Designed in 1956, this chair is now part of the New York Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection.

The Eameses relationship with furniture company Herman Miller began with moulded plywood chairs in the late 1940, after the company noticed the duo’s work in an exhibition of experimental furniture designs at MoMA. In the late 1950s Vitra began producing the Eameses’ designs for Europe and the Middle East.

Their approach to design was pragmatic. They were interested in the process of designing, were detail orientated and aimed to address problems, advocating that designers should take the time to notice the ordinary and preserve the ephemeral. This led to very user-friendly work. ‘Design as a solution not as a luxury’ was a guiding principle of their work.

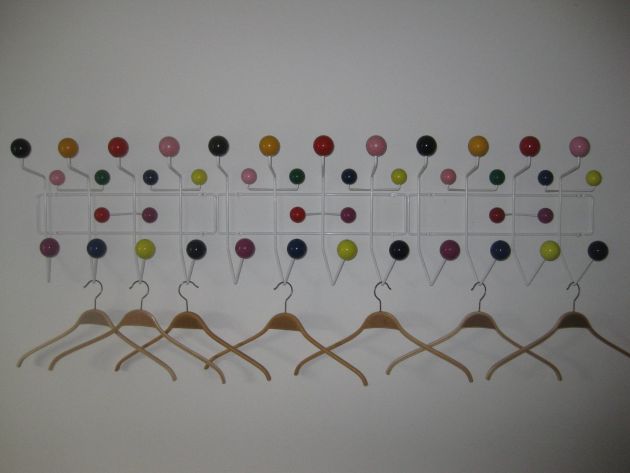

Hang it all for Vitra by Charles and Ray Eames. Photo by Smow Blog via Flickr

Hang it all for Vitra by Charles and Ray Eames. Photo by Smow Blog via Flickr

Around 1940 Charles met Finnish architects Eliel and Eero Saarinen, a father and son team who had a huge influence on him. They encouraged him to finish his degree (he had dropped out of an architecture course at Washington University) and he finished his studies at Cranbrook Academy of Art, Michigan. It was there that he met Ray.

Ray (born Bernice Kaiser) was Charles’s second wife. They were colleagues at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. After they married in 1941 they moved to Los Angeles. Ray was a trained artist and had learnt to paint in New York under the abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann. During her time in Manhattan she developed a visual language that would inform the shapes and colours used by the Eameses throughout their partnership.

While in Michigan Charles worked with Eero Saarinen on a new style of chair manufacturing, using a new material called plywood and moulding it into shape. He later continued this experimentation with Ray in Los Angeles, until World War II broke out and their work was diverted for a time.

The moulded chairs Charles had previously worked on were now replaced with moulded plywood stretchers and splints for injured soldiers. He noticed the beauty and purity in these practical tools and the splint became a point of departure for the Eames future design work. As Charles famously said, ‘we don’t do ‘art’ – we solve problems.’

When the war ended there was a new kind of customer for design, a new generation of suburban young people who didn’t have huge budgets for their home interiors. The Eameses dedicated their design explorations to finding aesthetically pleasing solutions to affordable design. Their work was elegant and practical, following the Bauhaus principles of form following function. More importantly however, was that the Eameses were able to take this concept and make it mainstream and easy to mass produce. The dynamic Eames team were able to introduce modernist design to middle class America.

They continued to innovate with materials in the 1950s, moving from plywood to fibreglass, plastic resin and wire mesh chairs designed for Herman Miller. Ray also worked with moulded plywood in a series of abstract sculptures that helped the duo test the limitations of the material and the shapes that could be created.

For much of their career, Ray was seen as the supporting partner in the Eames design empire. But her contribution should not be underestimated. She had an eye for detail and was able to soften Charles’s designs, giving them a human feel, a touch of colour or a sense of playfulness.

Eames House Case Study House No 8

Eames House Case Study House No 8

Their design partnership was manifested in their home – Case Study House No. 8, now known as The Eames House. Its structure was box shaped, built of glass and steel and very much the work of Charles. But the eclectic interior was much more in Ray’s style. It was made of prefabricated steel parts intended for industrial construction and was a milestone for modernist architecture. Case Study House was part of the Arts and Architecture magazine Case Study programme.

The facade was a mix of transparent glass and coloured panels to control the levels of light that entered the space. It encouraged indoor-outdoor living. Inside the house was furnished with the Eameses’s own designs and with objects collected on their travels, including tumbleweed they collected on their honeymoon.

The couple also had an interest in photography and film, creating several works including Powers of 10, Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire and Tops, a film about spinning tops. These cinematic experiments were ahead of their time: in an age of cinema, these were much more fit for disemmianation in the age of the internet. In this as in much else, the Eamses were ahead of their time.