A new book and exhibition at the Art & History Museum in Brussels tells the story of the multi-faceted career of the pioneer of the Wiener Werkstätte, who designed everything from silver teapots to marble-clad mansions

Photography featuring Josef Hoffmann, salle à manger du Palais Stoclet avec la frise en mosaïques de Gustav Klimt Moderne Bauformen XIII, 1914

Photography featuring Josef Hoffmann, salle à manger du Palais Stoclet avec la frise en mosaïques de Gustav Klimt Moderne Bauformen XIII, 1914

Words by Joe Lloyd

In 1905, Austrian architect and designer Josef Hoffmann completed the Purkersdorf Sanatorium near Vienna, a masterpiece of restraint that heralded the modernism to come. A few years later, he started work on the Villa Ast, an elaborate mansion with fluted walls and a cylindrical tower that builds on the language of the grand bourgeois villas of the 19th century.

Through his career as a designer, Hoffmann built cabinets with lyre-like wings, mustard pots that looked like alien spaceships and black-and- white storage units only slightly more decorative than a Robert Morris sculpture. How can we grapple a figure whose oeuvre is so full of twists and turns, contrasts and contradictions? ‘Efforts to impose a logical order on his production’, writes Adríán Prieto, ‘feel particularly tricky.’

Josef Hoffmann: Falling for Beauty embraces the multiplicity of Hoffmann’s work. Accompanying an exhibition at Brussels’ Art & History Museum which runs until April 2024, it offers a sweeping exploration of Hoffmann’s 60-year career as an architect and designer. It is lavishly illustrated, with a catalogue of works that captures the range of his practice. A spotlight on his designs for the textile company Backhausen presents an array of his patterns. Many show organic forms on square grids, poised on the knife edge between art nouveau and modernism.

Photography featuring Josef Hoffmann, poivrier pour poivre ou paprika, exécuté par les Wiener Werkstätte, 1903. Argent, cornaline, MAK, GO 2108 © MAK/Katrin Wisskirchen

Photography featuring Josef Hoffmann, poivrier pour poivre ou paprika, exécuté par les Wiener Werkstätte, 1903. Argent, cornaline, MAK, GO 2108 © MAK/Katrin Wisskirchen

Hoffmann was the son of a small-town textile factory owner in Moravia. In 1892 he moved to Vienna to study at the Academy of Fine Arts, where his tutors were the arch-historicist Karl Freiherr von Hasenauer and the architect Otto Wagner, who was soon to become the artistic leader for the new urban train network. After his studies Hoffmann joined Wagner’s architecture firm and became an enthusiastic member of the Vienna Secession, designing parts of its building and helming several international exhibitions, which helped to constellate the European design avant-garde.

Ornament began to slip away from Hoffmann’s work. In 1903, along with painter and designer Koloman Moser and the financier Fritz Waerndorfer, Hoffmann founded the Wiener Werkstätte: an association of artists, architects, designers and artisans who created artworks and design projects. It was an almost immediate success. His style became more geometric. He used so many squares and cubes that he gained the nickname ‘Square Hoffmann’. But, as Falling for Beauty shows, the story was not so simple. By the 1930s he was designing elegantly curved drawers, letter boxes and columns.

The Palais Stoclet, Hoffmann’s masterpiece in a Brussels suburb, naturally takes a leading role. Hoffman was commissioned in 1905 by the Belgian banking scion Adolphe Stoclet to build the Palais. Hoffmann and his Werkstätte colleagues designed every aspect of the building inside and out, creating a complete work of art. The exterior, in squares of white marble, is at once largely stripped of ornament and packed with details, including a statue-topped tower, windows inset into the roof as if battlements, and a belvedere. The interior is a carefully calibrated symphony of marble, enhanced by 7m-long friezes designed by Gustav Klimt.

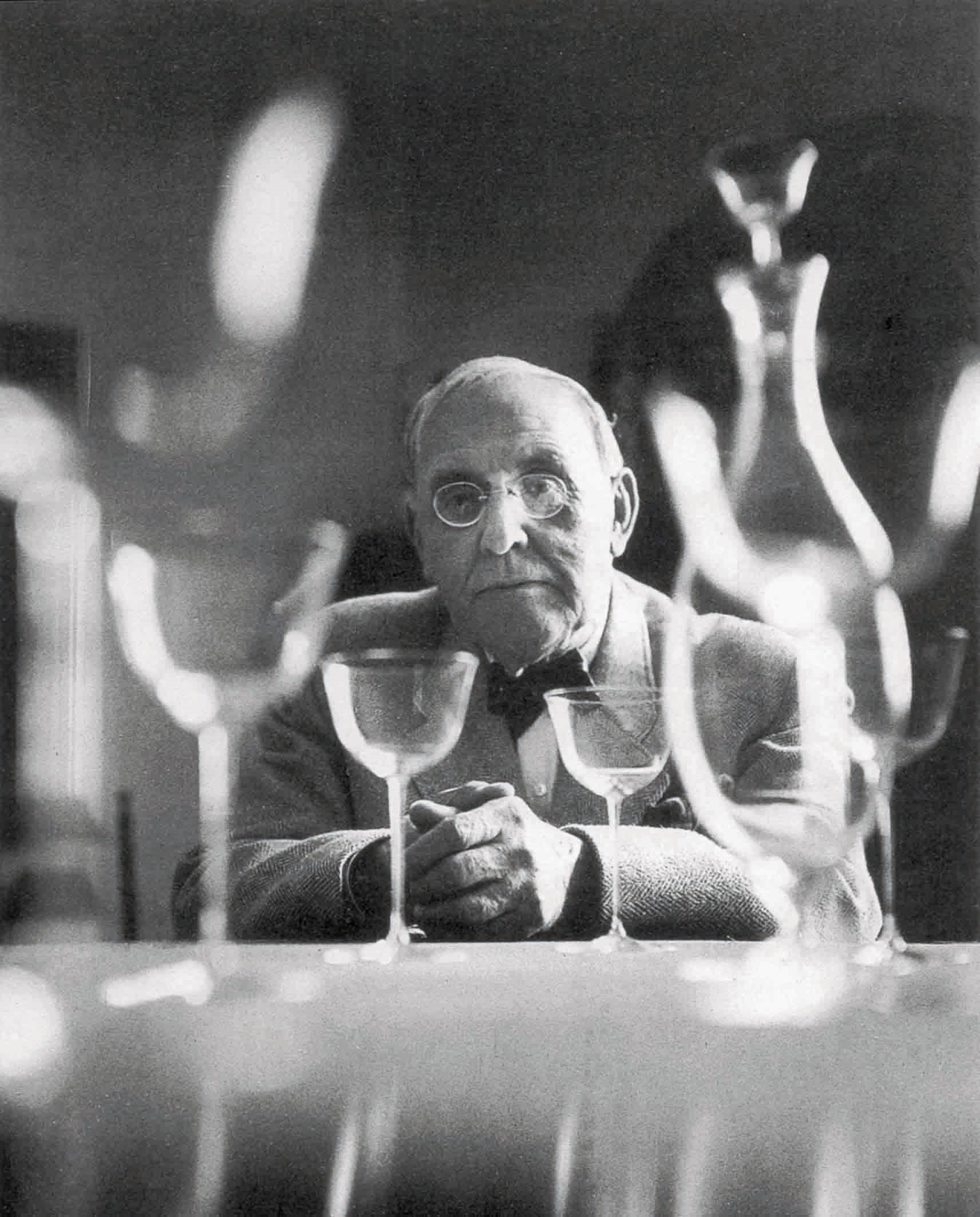

Photography by Yoichi R. Okamoto, Josef Hoffmann, 1954, MAK, KI 13740-5

Photography by Yoichi R. Okamoto, Josef Hoffmann, 1954, MAK, KI 13740-5

Simultaneously sumptuous and restrained, drawing on historical forms but simplifying them, the Palais Stoclet became an icon for art deco and modernist architects alike.

An interview with Aude Stoclet and Laurent Flagey, Adolphe’s descendants, provides insight into living inside and around an architectural masterpiece. It is accompanied by rare interior shots (the palace has never been open to the public).

When Adolphe Stoclet died, he asked to be buried with a ‘black and white handkerchief by Hoffmann’ and asked that ‘no changes be made’ to the Palais. He had fallen for the beauty of Hoffmann’s work – and who could blame him?

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter