Inside Es Devlin’s Memory Palace in Pitzhanger Manor

Inside Es Devlin’s Memory Palace in Pitzhanger Manor

The designer and curator of the next London Design Biennale tells Icon editor Priya Khanchandani about her practice, new works and grappling with the issue of sustainability

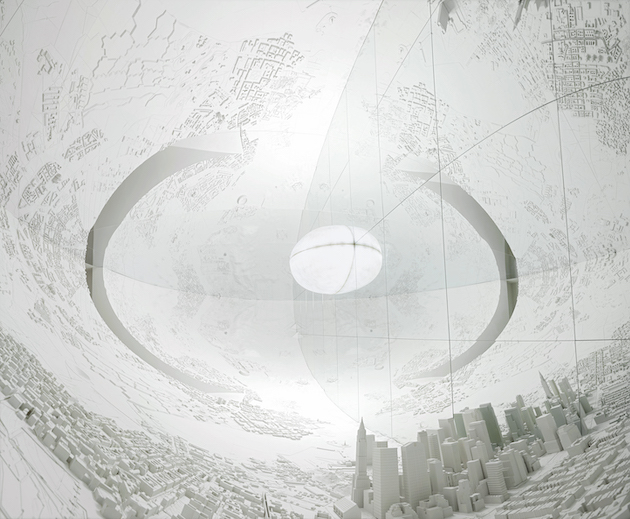

In what was once Sir John Soane’s country home, now the Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery in west London, Es Devlin has constructed a giant topographical model that echoes Soane’s prolific use of models. Titled Memory Palace, the model unfolds within a white, cosy space that the visitor can enter. Inside is a landscape of places where pivotal shifts in the human perspective took place. These range from the street in Montgomery, Alabama where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in 1955, to the place in front of Sweden’s parliament in Stockholm where Greta Thunberg began her school strike for the climate in 2018.

Priya Khanchandani: Is sustainability in design going to filter through to the upcoming London Design Biennale, which you’ve titled Resonance?

Es Devlin: Yes, absolutely. We are now curating and choosing all the submissions that are coming in from all parts of the world. We need to meditate and reflect on our current condition, but it’s not enough. It needs the next step, which is the call to action. How can anyone walking into the London Design Biennale come out with a series of steps they can take? What can they do in their lives, which will make them feel less hopeless? My focus at the moment is to try and counter hopelessness because actually we have, as a species, managed to shift gear mentally over the course of our time. We can do it again.

PK: In the Pitzhanger piece, how have you tried to reflect this idea of hope? Is it hopefulness or hopelessness?

ED: I think a lot of us feel somewhat hopeless in the face of how great the change to our daily lives needs to be in order to start to unpick some of the daily damage that we’re doing to the environment. One of my first steps is a big picture. So I wanted to start with a really wide shot. The widest view I could take at Pitzhanger was to look at 73 millennia and to look at the whole of the planet in one room in one sweep. You can see it all at once.

It’s a model landscape with buildings or places on it that are little markers, reminding us of all the points where significant shifts in our thinking happened. This is very subjective, so I’ve also left blank maps at the gallery for anyone to rewrite it. A really obvious example is when we all thought that the Earth was the centre of the universe until Copernicus, back in a room in a tower in Frombork, Poland, redrew the map and taught us that the Earth revolves around the sun. We changed our belief in the same way when we thought that it was acceptable that there was segregated bathrooms: in 1955, when Rosa Parks refused to move from her seat on that bus in Alabama, we began to change. We can. The first step is a reminder of that.

Another view of the Memory Palace

Another view of the Memory Palace

PK: Which aspects of the world today do you think we’ll look back on in 500 years and think ‘What were people doing?’?

ED: I think consumption. One of the points on the map is the office of Edward Bernays in New York. Bernays was Freud’s nephew who invented the phrase PR. He told the story that, during the war, propaganda was incredibly helpful to help Americans understand the war. Then he said, ‘After the war, we knew we had this very useful technique, but we could not call it propaganda any more. We had to find a new name for it, so we called it public relations. Then, we simplified that to PR.’

Consumer culture is a very recent thing. It’s only post-war that advertising began and the need to consume became the engine of the world. There’s a sequence in the Lehman Trilogy, a play that we did, that very much dwells on this. It tells the history of Western capitalism through the lens of one family, the Lehmans, over the course of three centuries. It really pinpoints just how much of a decision it was by certain people to send us into such a consuming culture. In my mind, that’s consoling because actually, it’s not innate to us. We’ll look back at ourselves from your point in 500 years’ time and say, ‘God, that was a weird moment when we all only found identity through buying stuff.’

Egg, a curved model of Lower Manhattan reflected in mirrors, displayed in New York, 2018

Egg, a curved model of Lower Manhattan reflected in mirrors, displayed in New York, 2018

PK: There’s a debate at the moment about the idea of the biennale and whether we can continue to justify the vast quantities of biennales in light of all these discussions about sustainability and trying to reduce consumption.

ED: I agree. I would say of all these gatherings, the most sustainable versions of the London Design Biennale and the most sustainable version of the World Expo is not to do it. That said, if it’s going to happen, if you’re going to gather these people and these materials, how can you make sure that an audience, once they’ve seen them, are going to shift their behaviour in a meaningful way? You also have to account not just for their creation, but for the rest of the lifecycle. Where’s all the material going to go after the biennale? How is it going to be reused? Where will it end up? If you can’t account for that, then you shouldn’t do it.

PK: One thing that’s really remarkable about your work is its breadth. You’ve designed huge stage sets for Beyoncé, you’ve designed for West End theatres, but also artistic installations. Do you see them as distinct practices?

ED: No. I think it’s all designed for the work to have a reach. It’s all collective, it’s all collaborative, it’s all an exchange of ideas. It might be that I’ve come up with the seed of an idea in my waking hours, but its development will always be in dialogue in the air between me and whoever I’m collaborating with. Then, it’s the case of literally going through life and looking for those like minds, looking for those people who are the right people. For example, it’s become more and more urgent to make some kind of penance for the amount of flying I do as a designer practising all over the world. I struggle with the word offset because offset almost feels like you have to offload.

When you ask about the practice, that’s when it’s really coming to maturation. It’s all of these points that radiate from me in different directions. I can start to weave them together in ways that, hopefully, will have a genuine impact.