The vegan designer turned heads at Milan this year with his inventive applications of soil, fungus and Dead Sea salt, writes Anna Winston

‘I don’t want to be the face of anything, I just want to give other people the opportunity to understand it and raise collective awareness so that people start to work with it… It’s something that comes from the heart, from belief. This is the starting point of a movement.’

Erez Nevi Pana is talking with intensity about vegan design, an approach to making products that involves no animal products at any stage in the process: ‘It represents the beauty in morality, the harmony that rises from non-violence principles. It’s a cruelty-free practice that encourages a harmonious stage of living.’

If the Israeli designer sounds like an evangelist, and that’s because he is, but in the best possible way. He practices what he preaches. Nevi Pana is currently one of the most high-profile, experimental practitioners of vegan design, after catapulting into the international press with a solo exhibition at Milan Design Week in April and being named as one of the winners of the second PETA Vegan Homeware Awards in June.

Titled Vegan Design – Or The Art Of Reduction and organised by curator Maria Cristina Didero, the Milan show was a strong statement. Mounds of material were arranged to reflect the different processes involved in fabricating each prototype. Among the highlights were stools made from material found in the desert, bound together and covered with a layer of salt crystals; a process developed after a failed attempt to make a vegan glue for binding furniture. The aim was not only to provoke designers into thinking more deeply about the ethics of their own processes, but also to poke fun at the design week’s heavy focus on aesthetics as a marketing tool.

‘We both wanted to share another perspective on design and design processes, in addition to a statement on these design parades that promote beauty and aesthetics while they support real horrors, covering the ugliness and grotesqueness of the sourcing,’ says Nevi Pana. ‘We [included] a mountain of all the trash we produced during the build-up to the exhibition; we had to be critical towards ourselves as well, to stay authentic and highlight the paradoxes.’

‘Everything looked raw and rough, because I wanted people to understand this is just a starting point. If everything was polished it would look like the end product. I want everyone to start practising this with me, between them.’

Didero described the designs as a product of ‘ethical subtraction’ and ‘free from guilt.’ It was well timed. Veganism has shed its woolly image over the past few years. In the UK alone, the number of people who identified as vegan went up by 400,000 between 2006 and 2016, and meatless food start-ups have seen a corresponding boom in investment.

Many are turning vegan for environmental reasons. Earlier this year, scientists announced that giving up meat and dairy was the single biggest way for an individual to reduce their impact on the planet. But full veganism extends beyond food. It means avoiding all products that take from or use animals. Nevi Pana became vegan five years ago, a decision that led first to a rethink about his clothes and then to fundamental questions about the materials he was using in his work. He found that animal products and by-products were often disguised in the supply chain and became frustrated that few designers were tackling the issue.

‘I started to see some designers rewriting their works because they see the topic of vegan design as a cool one, but it needs to be an honest change, a genuine one that comes from within, not some trendy topic. It’s about real principles,’ he says. ‘All the information is out there, [we] can’t ignore all the atrocities, we must act now. Besides the ethics, there is also an environmental side — animal farming is one of the most polluting industries out there! I hear so many green architects and designers speak about saving the world, and it always makes me wonder, are these designers and architects vegan? If not, the whole sustainability approach automatically dissolves.’

Nevi Pana is now studying for a PhD at the University of Art and Design in Linz, Austria, with a focus on vegan design, although he lives in Tel Aviv, a city that has one of the highest percentages of vegans in the world – perhaps as a result of people needing, in Nevi Pana’s words, ‘to find some good vibes and good energy’ as a counter to political and religious tensions.

There is a sense that veganism is really just an extension of Nevi Pana’s natural interest in biology, and his unusual, imaginative connection to the world around him. The 34-year-old designer grew up in Bnei Brak – an area just outside Tel Aviv known as a centre for Orthodox Jewry – with secular parents who ran a plant nursery in the middle of an industrial estate. His parents often worked late: ‘We didn’t have a regular childhood because we were always stuck in the plant nursery while they were working. While our friends were playing football, we were playing with plants. I believe it made me who I am. That’s how my fantasy world became so evolved and unique, because of the boredom. My fascination with natural materials is obviously related, the growing techniques of flowers and plants in the nursery resulted in my interest in growing objects.’

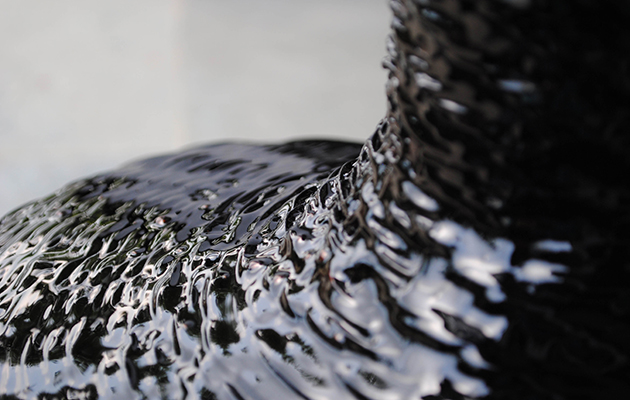

‘Growing objects’ is a very good way to describe some of his projects. Salt crystals on found materials is one example. Another is Soilid, a material created by combining soil, fungus and sugar to create a kind of dough that expands to fill a mould as the chemicals react. Once baked, this substance is tough enough to be drilled, cut or sanded. It was acquired in 2014 by Design Museum Holon, the institution also responsible for introducing Didero to Nevi Pana when she curated its show on Japanese design studio Nendo.

He studied design at the Holon Institute of Technology, and then moved to the Netherlands at the age of 28 to take a master in Contextual Design at Design Academy Eindhoven. The masters course is notoriously tough – of the 25 people that started the two-year course with Nevi Pana, only ten made it to graduation. ‘The conceptual and experimental approach of DAE just felt right, but it wasn’t easy,’ he says. ‘I was a real troublemaker. I played with materials that weren’t allowed in the workshops. My personality was solid and strong and they searched for rawness and flexibility that they can shape.’

Salt has been a recurring interest since a trip to the Dead Sea: ‘I went there to catch some sun and saw a white mountain in the middle of the desert – a mountain of neglected salt which is a by-product of the potash and bromine production, extracted from the water of the Dead Sea. Every year, 20 million tonnes of salt pile up in the Dead Sea Works. For me, this was a great deal to start working with a neglected material that nobody wants.’ So far, he has made a series of pristine white sculptural salt objects, a conceptual series for the gallery Friedman Benda that involved covering wooden objects in loofas that absorbed the salt from the Dead Sea’s evaporation pond, and more functional salt tiles and blocks.

Nevi Pana describes himself as an explorer – a ‘salmon swimming against the current’ – and his practice as materials research that evolves into design. ‘I love, love the conceptual and critical approach, but sometimes I feel like creating a functional object that will reach millions. At the moment, 90 per cent of my design is being consumed through the media, through my writing, exhibitions, lectures. I would love to cross the border to a more commercial application of design and expose the possibilities of beautiful and ethical ‘functional’ design.’

But for now, he openly admits to being ‘f*cking poor’, having given up a well-paid job as an interior designer to pursue his more conceptual, belief-driven work. ‘I’m not from a rich family. I just roll somehow. Today everybody wants a piece of you, but they want a piece of you for free. We are fighting every day, but we manage and the most important thing is the message you portray. You start to see a real change in other people’s minds. That’s what keeps me going,’ he says.

‘The shift towards a plant-based industry is critical. Future design must be in sync with nature — it must harness nature in a collaborative approach, rather than exploitation. We are conscious enough to discern the difference.’