|

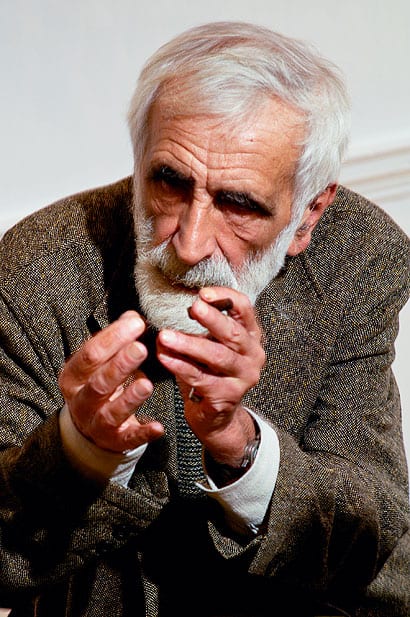

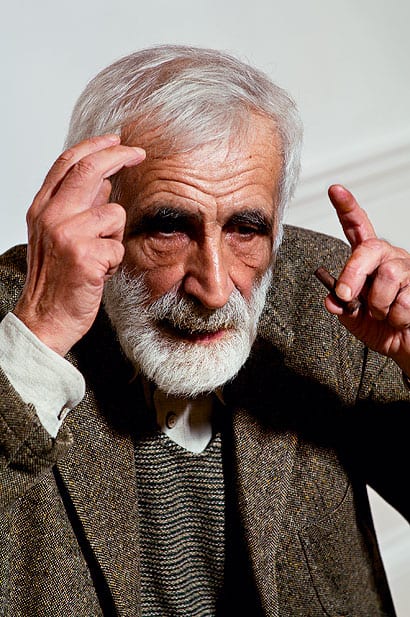

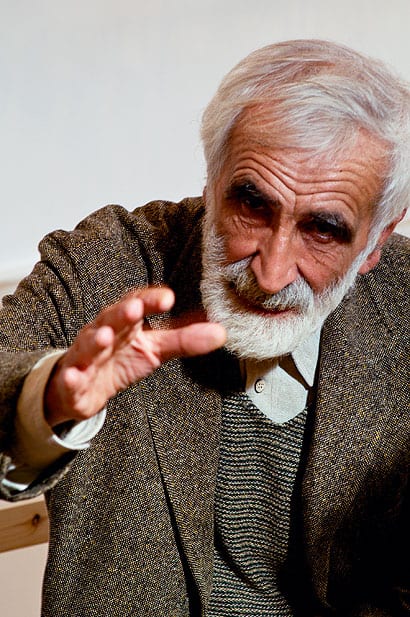

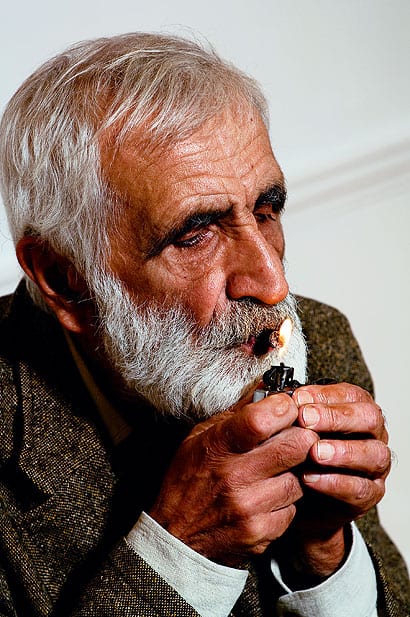

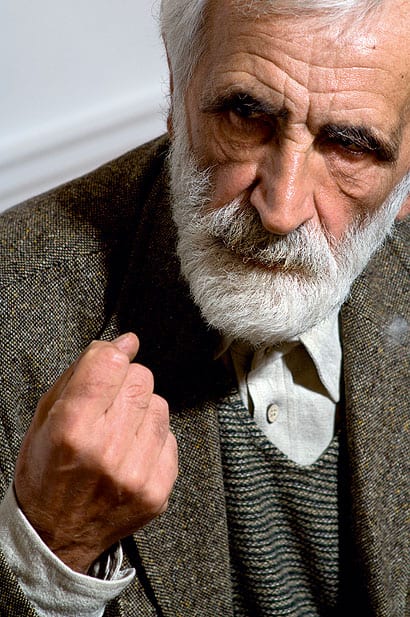

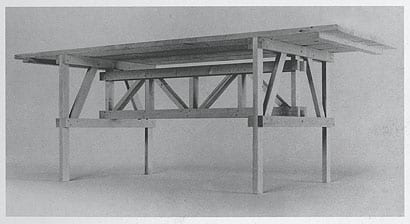

What’s the name of that English designer who did the spiral bookshelf, asks Enzo Mari, stirring the air with his cigar stub. Ron Arad? Yes. “Merda Pura!” he screams in Italian. “Pure shit,” deadpans our interpreter as Mari thunders away. “Pure shit! Who cares?” The outburst startles us. The 77-year-old Italian designer and legendary firebrand has been perfectly demure until now, slumping gently in his rural tweeds, an old man telling stories he has told countless times before. But the mere thought of Arad and all that he stands for awakes a terrifying passion in him. Now the gloves are off, and he goes on to savage the design industry, with its “pornography” of fashion-led products made “by the Italian mafia for the Russian mafia”. He bemoans the plight of design students and factory workers, the near impossibility of making a living, the exploitation, the stupidity, the lack of principles or standards. Or taste. He’s not shouting all the time – he prefers to catch us off guard. Now and then he pauses to smile mischievously, or to relight his cigar butt and knock a little ash into the polystyrene cup cradled in the hand that’s not holding the Zippo. So far, so Mari. The old warhorse is known for his doom-laden pronouncements on the state of design. Holding forth in the gallery of the Architectural Association, he doesn’t give me his beloved “Design is dead”, but apparently he said that ten minutes before I arrived. Around us is an exhibition in homage to Mari’s most famous project, the Proposta per un Autoprogettazione, or Proposal for an Auto-design. In 1974 he designed a series of DIY furniture pieces that required just some pre-cut pine and a few nails to assemble. He offered to post the book of instructions to anyone who would send him the cost of the postage, and had thousands of requests followed by 5,000 letters of appreciation. Some of these pieces are beautifully simple, others aggressively clunky. They were not intended as a viable means for the working classes to furnish their homes (in fact some accused him of fascism for making people do more work than they had to). Instead, they were a provocation, a counter-consumerist gesture aimed at making people focus on themselves rather than what was in the shops. For Mari, design is almost always a didactic act. Looking around the AA gallery, the young designers reinterpreting his project appear to have largely missed the point. All the pieces emulate his bare pine aesthetic but few are useful – there is no invitation to flout the manufacturer-retailer food chain. To break the ice, I ask Mari what he thinks of the show. Twenty-five minutes later I chuck my list of real questions on the floor because we haven’t got to any of them yet and he’s still getting into his stride. “I cannot give an immediate answer because I ask myself the question of how the millions of young designers in Europe can survive today,” says Mari. “There are more schools of design than stones in the streets. They produce a hundred times more designers than the amount of objects we can produce. Sixty percent of them will not be able to do the profession that they wanted.”

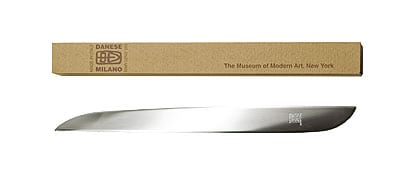

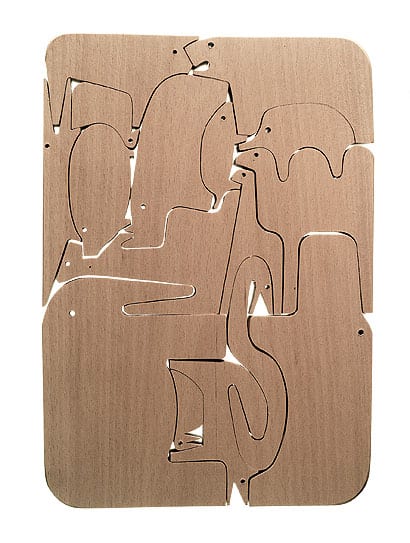

A lifelong Marxist, Mari often discusses design in terms of its producers rather than its users – it is the workforce he cares about, not the consumers. He worries about how they’ll earn a living in a world whose values are completely warped. He likes to tell the story of a cheap wooden bed that he designed for Driade that didn’t sell “because it was too cheap!” Mari believes design has become distracted by luxury and is caught in a vicious cycle of novelty – mundane observations, except that for him schools are complicit in the problem. Instead of a profession, they teach personal expression. “I find problems and defects in these chairs,” he says, looking around. “I’ve got to blame the schools.” He points to some hybrid chairs that he describes as “stupid copies of Martino Gamper” – Frankenstein task chairs bolted with bits of pine. “Does he think he can sell these for £20,000 each? When I did my ones 40 years ago it was a desperate act.” The son of an artisan, Mari’s early years were preoccupied with helping to support his family. As a teenager he was a street peddler for whom “being an employee was a dream”. He didn’t go to high school or university, and thanks his lucky stars that he was never “castrated” by a design school. Eventually he enrolled at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, moving from painting to sculpture to stage design. He finally took up design in the late 1950s, and made a name for himself with innovative exhibition designs and a series of wooden animal puzzles for Danese. After that came scores of objects for the classic Italian brands: kitchen utensils for Alessi, everything from vases to letter openers for Danese, furniture for Magis and Zanotta. However, he never achieved the kind of success enjoyed by contemporaries like Achille Castiglioni or Vico Magistretti. Mari was more the intellectual, the polemicist, the thorn in the system’s side. The Autoprogettazione project best sums him up. Its asceticism was a slap in the face of modern life with its ready-to-go plastic taste. One design in particular, a bed crudely cross-braced with bare planks, reads like punk anarchism and looks as though it belongs in a gulag. Mari complains that only one percent of the people who wrote to him about Autoprogettazione understood the project. Often they praised its rusticity, which suited their cabins in the Alps – they simply didn’t get it. Mari occasionally harks back to the old days, when he and his design colleagues (Castiglioni et al) felt like they were building a new society. That, he feels, is dead, “like a religion”. These days he can’t do any new furniture, he says, even though he is “still strong” and knows a damn sight more than these youngsters. For one thing, the manufacturers already know what they want because they know what sells. “They say, ‘You are totally free to do whatever you want’ and I say, ‘Can I fire the whole technical department of the company? Can I fire the commercial department, all the marketing, can I change the CEO? If I can do that then I am free. Otherwise you are just taking the piss out of me.'” Here Mari relights what’s left of his cigar, threatening to set off the fire alarm. In the past Mari has talked of “proper” design, so I ask him what he means by that. Its pillars, he replies like a good socialist, are “equality” and “the standard”. That sounds rather like Ikea, I suggest. Is that “proper” design? His answer starts off perfectly calm but crescendos rapidly. “I’ve bought objects from Ikea myself, they are very cheap. But they are cheap because of the blood of the people,” he says, beginning a tirade against the Swedish company’s business practices and what he sees as its exploitation of struggling workers in developing countries – at one point he tosses in the word “genocide”. Definitely not Ikea then.

Mari’s angry old man act may be eminently lampoonable, yet there’s something appealing in his contrarianism – more than that, something valuable. He despises yes men and compromisers. He makes resistance sound like the only honourable methodology. “Often when I speak with young people they ask me but if you’re so critical why do you do this job?” he says. “And I answer: I do this job because I fight for the right to think. I don’t know if the things I do are so good, if I am so good, but when I fight against all the contradictions that my projects raise then I understand the world – that’s it.” And there certainly are contradictions. A designer who hates consumerism and merchandise (“the genocide of the brain”). A working class intellectual with little faith in the common man. It would be easy to write Mari off as out of date, especially in his politics. Here we are swiftly negotiating the terms of the post-industrial era and he’s still worrying about “the workers”. Well he’s quite right, industry no longer guarantees you a job for life. The atomised, globalised world of the 21st century must be a worrying place for one of the heroes of the Italian post-war miracle. Reaching for my notebook, he draws me a graph representing the state of things – population explosion, global warming, immigration – essentially an index of pessimism, which descends abruptly off the bottom of the page. No wonder he fantasises sometimes about retiring to a village to make furniture for the locals, simply, “like a baker or a pizza-maker”. In fact, his vision for a successful post-industrial model sounds distinctly like the pre-industrial past – a return to strictly localised production by craftsmen. Rules. That’s what he thinks we need. That’s what design schools ought to teach, not “creativity”. Design used to be about a common grammar, now “everyone invents his own language”. All he sees is a Babel of creativity. “If someone tells me to be ‘creative’ I just want to give him a punch in the face!” Every culture needs a Mari, he’s our Savonarola, preaching the bonfire of the vanities. Or perhaps he’s just our politically incorrect cab driver moaning that the world’s gone to the dogs. The question is who’s going to pick up his mantle when he’s gone?

Autoprogettazione “self-design” projects, 1974

Timor table calender for Danese, 1967

Ameland paper knife for Danese, 1962

16 Animali for Danese, 1959, reissued by Alessi in 1997

Box chair for Castelli, 1971, reissued by Aleph in 1995 |

Image Mark Guthrie

Words Justin McGuirk |

|

|

||

|

EM03 colander for Alessi, 2000 |

||