|

|

||

|

The design duo’s Open Home collection for John Lewis launched this month. Debika Ray spoke to them last year at their London studio about design, architecture, resolving disagreements and their exploration of Indian classical music The work of London-based design duo Nipa Doshi and Jonathan Levien is a celebration of different disciplines, cultures and methods – from visual references drawing on Doshi’s Indian background to Levien’s training in fine cabinetmaking. The husband and wife team, who met while studying at the Royal College of Art, established their practice in 2000. Since then, they have worked with some of the world’s biggest design brands, but that doesn’t mean they’ve stopped seeking new avenues for creative expression. ICON I’m told that, Nipa, you’ve taken up Indian classical singing and that you both play [the Indian percussion instrument] the tabla. How’s that going? JONATHAN LEVIEN Really well. It’s actually my third year playing the tabla. I was looking to do something completely outside of design, to reach out into a different world and bring new ingredients into my work. There’s a time, rhythm and proportion in music that you can relate to design in a visual way. I also love learning transportable skills: yoga, taekwondo, classical music. These are things you can study and carry with you wherever you go. NIPA DOSHI What I like is that it’s very abstract: Indian music is not something you read and play – you memorise it to the point you can improvise. It’s also mathematical – you have to stay within the frame of a 16- or eight-beat cycle, so you’re making a lot of calculations in your head. I’m a very mathematical person. I’m surprised when people think of my [design] work as more decorative or ornamental, because I think it’s very logical. JL That balance between geometry and intuition is, for me, very interesting. When I’m working with form, sculpting pieces, I like to explore the coming together of the two. Freeform comes from the heart, while geometry is when you apply rules and parameters. They’re necessary partners in design – that’s what leads to design with clarity and structure, but also with feeling and expression. ICON How does that manifest itself in your work? ND When we started out we did a lot of research-based projects, for example our installations for the Wellcome Trust and our work with Intel. I was very comfortable doing projects that required strategic thinking, but that’s not enough for me – translating that into a product or campaign is where we come in as designers. Another example is when we’re doing pattern: the form of our Paper Planes chair, for example, resulted from how you could tailor the fabric so the lines met in a certain way. The Charpoy collection also has a strong grid, with the pattern of chaupar [an ancient dice game] embroidered on it. I did a lot of work in resolving the pattern to fit the shape. Similarly, with the Rabari rug, we started with a grid then disrupted it – like [improvising with] music. ICON How did you develop the pattern for your recent collection for Kvadrat? ND It started from an architectural point of view. It’s a collection of curtain fabric, for use on large surfaces and buildings. When you look at them, you don’t really think of pattern – more of texture: machined concrete, perforated metal, iridescent glass. We put together a collection of hard materials when we were designing it. JL That’s a big part of our work – letting the making process be an instrumental part of the outcome. For this project, we made panels in cast plaster and layers of tape, then cut into them and peeled off layers to create a chiaroscuro effect, with the illusion of light and shade. I love the idea that we’ve used a different material to generate ideas for a fabric.

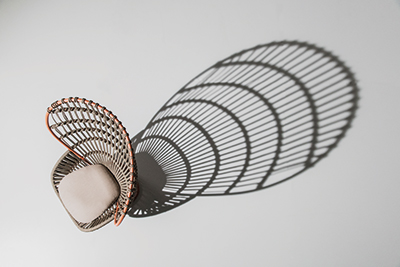

Cala armchair, 2016 (top), and Geometrics outdoor fabrics collection, 2016 – both for Kettal ICON You mentioned architecture: do you have ambitions to work on that scale yourselves? ND Yes. I’d love to design a museum, but I would focus on the other activities you’d do in the space apart from looking at art or objects. I think of museums as public or community spaces, where you go to feel good. If I go to the Tate, for example, I don’t always go to see an exhibition – there might just be one aspect of the space I want to be in. The SESC Pompéia in São Paulo is a fantastic example of that, because it’s a cultural centre, but you also have elderly people who come there to read the newspaper, meet or have lunch. JL I think architecture is a natural progression for us. Our work is, in any case, a study in the relationship between people and their immediate space – we see objects as creating spaces around people, framing them. What’s really exciting about the idea of doing architecture is the social aspect. Our Das Haus installation for IMM Cologne in 2012 was an indication of how we would start an architecture project, thinking about where the site is for a house, how you approach it, how it’s related to the neighbourhood, how you go inside and the different activities that take place in there.

The Nami Chair (top) and the Mudra Chair, from the John Lewis Open Home collection ICON Returning to furniture, I believe you’re working on a collection for high street retailer John Lewis at the moment. JL Yes. It’s a collection of pieces called Open Home that looks at the current way we live – in larger, open spaces, for example – and at how we can create microcosms of space within our home. We proposed moving away from the idea of furniture as a sedentary, heavy mass, towards something more light and sculptural. The sofa and entertainment system is often seen as being the hub of the home, but I thought it could be interesting to create other spaces – a light, compact armchair with a reading lamp you might put to one side, for example. We think of these pieces as allowing people to get more out of their home. ICON How do your skills and approaches to design differ from each other’s? JL Nipa is really good at colour. ND He’s pulling my leg. I’ve always been reluctant to do colour, because I always feel it’s ‘something girls do’ – or at least that textiles girls do, not women who study industrial design. But when Kettal asked us if we’d work with colour on a range of outdoor fabrics, I said yes. I had to succumb to it and say, okay, I’m actually good at colour. It comes to me intuitively. Jonathan is very fast and efficient, whereas my process is more internal and fluid. He’s not fazed by the complexity of a project. I think he has this feeling that, no matter what the idea is, we can make it happen – he’s not frightened of making something that’s not right and arriving at [the solution] through a process of trying. JL That’s the confidence that comes from a background in making. I think my way of working is more physical, more three-dimensional – using sculpting to explore ideas. Nipa is more into drawing and collage. What’s interesting is that there’s scope for us to interpret each other’s work. I love seeing Nipa’s two-dimensional sketches and giving them a physical form. ND What I’m striving for is to create something beautiful – and I use that word with the utmost respect. For me, the beauty of an object is in the way we use something: our gesture when we sit on a piece, fold a fabric, roll or unroll a carpet. There’s a lot of beauty in the actions around design. I try to make sure that the object incorporates those beautiful gestures. That comes very much from my Indian background: we have rituals around everything from birth and marriage to death – strict guidelines of how to do things.

Do-maru armchairs and Maru tables for B&B Italia (2016) ICON Do you think someone using your design is conscious of these ideas? ND Absolutely. How can you interact with a piece of furniture, for example, and not discover details, the way something is stitched or the way you sit on it? I definitely think people enjoy our process, even if they don’t know it. JL Yes, the complexity can be in the thinking, but it doesn’t have to be in the outcome. ICON Do you ever disagree on your direction? ND All the time. JL Yes, we have to convince each other. I have to sell to Nipa quite a lot. It’s what keeps the whole thing alive – the constant need to reconcile our ideas.

Paper planes chair for Moroso (2010) on Rabari rug for Nani Marquina (2014) ICON You’ve said previously that the starting point for your work is ‘an exchange of cultures’. Could you tell me more? ND Jonathan comes from a culture of making. I come more from a visual culture. Then, of course, there’s the cultural mix of me coming from India and Jonathan being from the UK. I’ve found that in India we’re always worried about how we’re going to make something. I feel that when you grow up in a more industrialised country, where methods of manufacturing are more established, you’re more free – you feel you can make anything. When we started working, I had a limited knowledge of what was possible in terms of manufacturing. That was a big learning curve for me. JL I think there’s a willingness in both of us to want a part of the other person: for example, I would never come up with ideas like the Principessa daybed, or the Charpoy or Rabari collections.

Dapper lounge chair for Hay (2016) ND And I could never come up with the Almora chair: I just don’t have that very industrial understanding of form. I can visualise a feeling, but not necessarily a piece of that complexity and yet simplicity. We work together because I want something Jonathan has that I don’t have. I think that’s also what makes a beautiful space: contrasts and contradictions, when you combine something handmade with something industrial. I think our work is about creating a space that’s human, plural. That’s the kind of world I want to live in – where different kinds of architecture can coexist, where industrial design and handmaking work together, where you have sensuality but also rationality and precision, but with things left a bit open, the ephemeral and the tangible. For me, that’s what makes a beautiful world or a beautiful city. This article first appeared in Icon 162, which you click here to read more about. Doshi Levien will discuss their new collection for John Lewis and more at Clerkenwell Design Week on 24 May |

Words Debika Ray

Portrait Rob Greig

Above: Levien and Doshi in front of Pilotis, an installation made from their collection of curtain fabrics for Kvadrat (2016) |

|

|

||