|

|

||

|

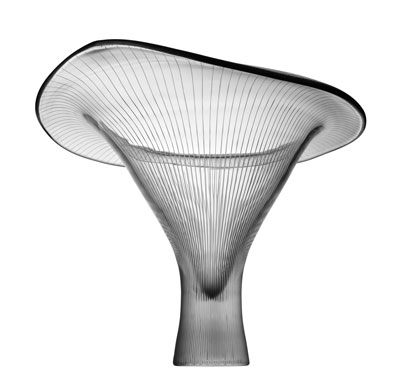

For a young nation, Finland has a rich design history – not just its humane modernism but also the wild primitivism of the postwar age. Is it now time for a new voice to emerge? The history of Finnish design is messy. You wouldn’t guess it walking through an upmarket Scandi store, admiring the restrained modernism of Kaj Franck’s Teema plates or Kartio glasses, both staples of today’s stark, faux-Nordic interiors. Or Alvar Aalto’s 60 stool, a 1930s masterpiece we barely notice thanks to its ubiquity and perfection. Over a million have been sold; its variants furnish Apple stores worldwide, their pale birch matching the firm’s frigid aluminium aesthetic. Yet in its so-called golden years – the late 1940s to early 1960s – Finnish design conquered the world for entirely different, and highly idiosyncratic, qualities. Aalto’s modernism faded from view, replaced by sculptural glass vases, highly glazed ceramics and painterly textiles by such mercurial talents as Tapio Wirkkala, Timo Sarpaneva, Dora Jung, Yki Nummi and Gunnel Nyman. Finland’s exhibits won medals at Milan Triennales like confetti, greeted by a heady cocktail of praise and condescension, hailing the creative spirit of a hardy people on the periphery of Europe, ‘only partially freed from the natural state’, as Swedish designer Tyra Lundgren charmingly put it. Finnish design was portrayed as a fusion of East and West, its abstract forms contrasted with the clean, civilised lines of modernism. |

Words John Jervis

Above: Alvar Aalto, Stool 60 (1933) for Viipuri Library (now by Artek); seat decorated by Mads Nørgaard (2013)

Finnish design was portrayed as a fusion of East and West, its abstract forms contrasted with the clean, civilised lines of modernism |

|

|

||

|

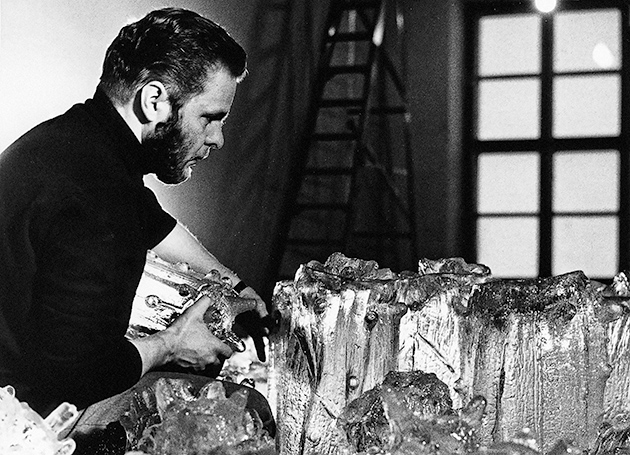

Timo Sarpaneva assembling his Ahtojää sculpture in the Finnish Pavilion at Expo 67 Montreal |

||

|

This extravagant tableau was welcomed by design professionals in Finland, capitalising on (and flattered by) their unexpected international success. The Finnish Society of Crafts and Design disseminated ripe texts describing a frugal yet vital nation, in harmony with nature yet struggling for survival, embracing the subtle colours of nightless nights. The echoes of Japanese essentialism were no coincidence: a self-congratulatory love affair between the two nations began, celebrating their innate, unsullied understanding of nature and mutual love of saunas. And, in 1954, Finland hitched up to the Scandi design bandwagon, an alliance that thrives to this day. Meanwhile, Sarpaneva and Wirkkala enjoyed playing the heroic barbarian, the former proclaiming: ‘My grandfather was a shaman … I am just that kind of primitive being. I’m also awfully childish, this is my strength.’

Tapio Wirkkala, Kantarelli vase (1946) for Iittala But the design of this era was an anomaly, a return to craft caused by postwar austerity and stiff reparations levied by the USSR. And its peculiarity – its self-proclaimed otherness – ensured international interest. The precedent, if any, was the national romanticism through which architects and designers expressed the aspirations of the fledgling republic in the years after independence in 1917 – a mixture of Finnish motifs and neoclassicism, in explicit reference to Athenian democracy. Advocates such as Arttu Brummer celebrated applied arts, indigenous crafts and the role of artist-designers, and passed these concerns to the postwar generation through their roles in education. Yet it was international modernism that dominated in the 1930s, propelled by belated industrialisation and a public sector keen to achieve both a modern society and a Western identity. Young designers, inspired by international design fairs such as the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition, turned to standardisation, functionalism and modernist aesthetics. In a largely agrarian economy, in which forestry accounted for four-fifths of exports, timber was crucial to such ambitions, despite the campy tubular-steel furniture of Pauli Blomstedt, or indeed Alvar Aalto’s early cantilevered chairs in metal.

Alvar Aalto, Armchair 41 (1932) for Paimio Sanitorium (now Artek) Artek – founded in 1935 by Alvar and Aino Aalto, with art historian Nils-Gustav Hahl and art patron Maire Gullichsen – reinvented wood, and more precisely birch, as a modernist material, marketing such designs as Alvar’s armchair for the Paimio Sanitorium (1932) and his stacking stool for the Viipuri Library (1933). These required the development of new techniques for bending laminated wood and plywood, and the stool’s part-laminated ‘L leg’ proved revolutionary – a mass-producible, standardised wooden component, adaptable to multiple applications.

Early press photography for Alvar Aalto’s Y leg, introduced in 194 Artek’s original manifesto proclaimed an unlikely intent to marry art and technology through three streams – modern art, propaganda and ‘industry and interior design’ – to attain ‘increased worldwide activity’. This was achieved with stupefying speed, thanks in part to the acclaim that had greeted Aalto’s furniture on such foreign forays as the 1933 ‘Wood Only’ display at London’s Fortnum & Mason, a vital breakthrough in Finland’s largest export market. Artek’s products were soon sold by Heal’s under the slogan ‘Better furniture for better times’, and graced locations as varied as the De La Warr Pavilion and the Finsbury Health Centre. This was a modernism more palatable, more natural, more complete and more affordable than anything on the continent. Yet Artek’s furniture was not truly mass-produced: fulfilling export orders proved hard, and prices in Finland ensured it was associated with a cultured elite, a reputation it never quite shook off.

Kaj Franck’s Kilta range (1952) for Arabia Yet, despite its postwar eclipse, Artek’s humane modernism was to outlast all the artistic predilections of the 1950s ‘golden era’. Even as expressionism and applied arts held sway, a backlash was underway. Kaj Franck – one of the cadre lionised at Milan, but with his own sober, moral take on modernism – criticised the ‘unwholesome trends’ of the time in trenchant terms: ‘The designer has been turned into a sales gimmick for design and as a result definitions have become obscure … Instead of living on the designer’s name, [products] should exist on their own merits.’ Working for Finland’s leading ceramics manufacturer, Arabia, Franck designed the economic yet beautiful Kilta range, with its exacting flat surfaces, in 1952 (updated in 1977 as the omnipresent Teema). It was a clear rejection of the impractical, decorative and unaffordable. He also attempted to phase out signed products and slammed star designers for parading their life, family and genius to an eager press. Others followed suit at Arabia, including Ulla Procopé, with her rustic yet fluid ovenware and Antti Nurmesniemi, with his colourful enamelled coffee pots. Elsewhere, Ilmari Tapiovaara designed elegant, utilitarian chairs for Keravan Puuteollisuus and Asko – including the Domus, a huge British success – at prices that Artek could not match.

Scissors by Olof Bäckström for Fiskars (1967) Such efforts were bolstered in the 1960s by a new generation of designers who rejected expensive studio pieces in favour of a functional modernism that served the needs of a thriving welfare state. An obvious example is Olof Bäckström’s orange-handled scissors for Fiskars, but uncredited design for health and education, or for rapidly diversifying industries, was equally prevalent. Protected by Finland’s closed market, the old design firms remained powerful and, to the chagrin of many, persisted in working with the heroes of the previous decade. Even so, the relevance of these primitive geniuses slowly waned: some retreated to craft, some sold their talents abroad, others adapted. Wirkkala prospered thanks to his eclectic talent, adding toilet seats, door handles and vodka bottles to his output. Sarpaneva’s cast-iron pot for W Rosenlew, with its detachable wooden handle, was a mildly ridiculous marriage of functionality with Finnish identity. Marimekko, with its relaxed cuts, escaped much of the criticism, adopted as a uniform for modish egalitarians.

Eero Aarnio, Pallo chair (1966) for Asko (now by Adelta) and Yrjö Kukkapuro, Karuselli chair (1964) for Haimi (now by Artek) As the economy flourished in the 1960s and 70s, swaths of new consumers preferred affordable, comfortable and somewhat chintzy furniture, much of it ‘British style’, thereby undermining the teleological narrative of modernism. The need was met in part by domestic companies, but also by imports – the globalisation of economies and tastes had finally caught up with Finland. A few firms tried to reflect international trends – Haimi produced Yrjö Kukkapuro’s classic Karuselli lounger in plastic; Asko, the nation’s largest furniture manufacturer, struck a rich seam with Eero Aarnio’s fantastical fibreglass chairs; Harri Korhonen set up Inno to produce his own neo-modernist designs in 1975; Avarte oversaw Kukkapuro’s conversion to postmodernism in the 1980s. Yet decline was inevitable as Finland accepted open markets, imports overtook domestic production and popular interest waned. The loss of the huge Soviet market and the IKEA invasion proved fatal to most firms.

Yrjö Kukkapuro, Experiment chair (1982) for Avarte and Ilkka Suppanen, prototype for the Nomad chair (1994) Talented designers emerged in the 1990s, including Stefan Lindfors, Timo Ripatti, Ilkka Suppanen and Harri Koskinen, yet, with the possible exception of Koskinen, their products were cosmopolitan rather than noticeably ‘Finnish’. Government support crystallised around other priorities: relationships between design education and the corporate field, and the needs of a knowledge economy. Golden child Nokia fell by the wayside but many industrial firms, from audio specialist Genelec to forestry manufacturer Ponsse, did integrate design-thinking into their structure.

Harri Koskinen, Block lamp (1996) for Design House Stockholm Today the three giants of traditional Finnish product design – Iittala, Marimekko and Artek – thrive, partly on the strength of their heritage, but the latter two in particular have regained design clarity after struggling in the 1980s and 90s. Marimekko had effectively monetised its retro appeal, but in 2014 hired Swedish creative director Anna Teurnell to refresh its brand. Artek – now owned by Vitra – has employed outside voices such as Konstantin Grcic, Daniel Rybakken and, with great success, the Bouroullecs to respond to the firm’s history of systematised components.

Aurora lanterns by Elina Ulvio (2013) This embrace of overseas talent is a cause of grievance among those young Finnish designers who don’t wish to pursue industrial or service design, or retreat into craft. With few domestic options, they are left to hawk themselves on the global market. Jukka Savolainen, director of Helsinki’s Design Museum, welcomes the new diversity around design, but admits that a lack of manufacturers and of government support hinders practices seeking international visibility. Hanna-Kaarina Heikkilä, co-founder of the much-praised Studio Finna, is currently working at IKEA while her partner Anni Pitkäjärvi oversees the studio. She describes the challenge as ‘tricky – big Finnish companies are no longer brave in using new designers. We always end up working with Danish firms, who have a vision about how they want to develop their design language.’ Elina Ulvio, heralded as the ‘next big thing’ last summer, is even more scathing: ‘Sadly there are very few possibilities for young designers in Finland. Firms like to play it safe; the main triumphs are still the classic designs by dead designers. The Danish use their design heritage and skills in a vibrant way, updating and maintaining while benefitting from and supporting the fresh visions of young designers … This kind of pioneer-thinking was active in Finland during the golden age of modernism, with the outcomes we are all proud of. The same level of braveness and confidence is needed today.’

Keshiki by Hanna-Kaarina Heikkilä of Studio Finna (2015) The Finnish tag has benefits. Heikkilä feels that ‘it brings attractive ideas into people’s heads, even if they have no idea what contemporary Finnish design looks like or means.’ Terhi Tuominen, winner of Design Forum Finland’s 2009 Young Designer award, agrees it can be useful, but ‘can also hinder new explorations when designs don’t easily fall into stereotypes of what Finnish design is’. Analysing the close relationship Finns have with design, he cites the concurrence of urbanisation and modernism, saying: ‘I see [Finnish design] as committed to improving the quality and functionality of everyday life. We live in a harsh climate, hence things need to be practical and work smoothly. We see beauty in objects stripped to bare essentials and give power to a detail or characteristic of the material.’ Limited-edition Kinos vase by TuominenPatel (2016) This statement – like many by young Finnish designers – combines 1930s internationalist ideals about the scientific application of design to create a just, modern society, and an abiding belief, fostered in the 1950s, in the otherness of Finnish design. It’s a position that can be challenging – good copy for lifestyle magazines, less useful if you aspire to be the next Yves Béhar. Mantras around nature, simplicity and purity are tempting to companies, designers and even government bodies wishing to capitalise on positive preconceptions abroad – one quarter of Finnish exports are still classified as ‘design-based’. But, as Savolainen says, ‘the biggest problem is that the public’s general perception of design is still based on that 1950s idea of craft-based designers making beautiful objects, and forgets that it’s about making a better life for all of us.’ Perhaps this should be the moment for Finnish designers finally to cast off the hoary, alluring language of the coffee table and, inspired by their modernist predecessors, recast their identity and their role in society. After all, they managed it a century ago. This article first appeared Icon 171 – read more about the issue here |

||