|

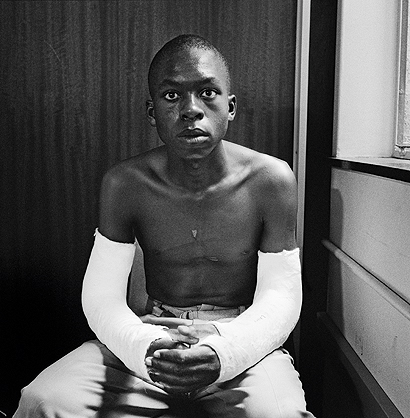

Each spring creatives from around the globe migrate to Cape Town, as they have for the past twenty years, for a summit that explores how innovative ideas might help Africa Design Indaba, a conference based in Cape Town, was started in the heady days after the collapse of apartheid. “1994 was a completely euphoric time,” says founder Ravi Naidoo. “We were all just imbued with such a positivity and energy. We all wanted to raise our game, to do more, because we understood that unless we could make the economy work, this political miracle would not mean a dot.” Naidoo, who has an infectious energy, masterminded the bid for the African World Cup and was also responsible for helping the first Afronaut reach space. He believed that what the fledging democracy needed, if it was to not only rely on the country’s abundant natural resources but add value, was a focus on creativity, innovation and design. His team decided that a conference devoted to these themes was the best way to inspire such change. “We had no frame of reference at all,” says Naidoo, “One thing that was nice about it was that it wasn’t a derivative gig. Because of apartheid we hadn’t stepped out of the country to go to any design platforms so we just based it on first principles – what is it that we wanted to say? What is it that we wanted to activate?” The inaugural event, with a practical focus on graphics and advertising, attracted an audience of 200. This year 3,500 people crammed into a conference centre in the centre of the city for three days to listen to a range of distinguished international delegates (Heatherwick, Fukasawa, Sagmeister), and these talks were beamed by satellite to other cites around Africa, making it the biggest design event in the southern hemisphere. “In 1995 we realised that we need to catch up with the world,” Naidoo says. “We were stricken with academic boycotts and economic sanctions, living in this cloud cuckoo land, this weird kind of social engineering experiment in South Africa, and we needed to get on the global express.” Indaba always had international ambitions: at the conference South African creatives are able to take stock of what is going on in Tokyo, Rio, London and New York and are encouraged to emulate those achievements. Naidoo’s team travel the world, making a point of visiting all of the studios of the speakers they invite, and have a good nose for scouting new talent (Adjaye and Behar, for example, came early in their careers), much of it fresh from the best design schools. All speakers receive a gold medal: “For us it’s like the Design Olympics,” says Naidoo. “It’s serious, and we want to give it the gravitas and stature it requires, so everybody leaves the main stage with a medallion of one ounce of pure gold.” Speakers are also thanked with what Naidoo refers to as “good old-fashioned Cape hospitality”, which is another key draw. On the first evening all the delegates are driven in chauffered Minis to the Blue Train, South Africa’s Orient Express, where they have cocktails and dinner as they rattle through wine country. They are put up at the five star Mount Nelson, a pink stucco vestige of colonialism, and treated to helicopter rides around Table Mountain and Robben Island, where Mandela was imprisoned. They have dinner at the private homes of architects, designers and patrons, lunch at a luxurious vineyard in Stellenbosch, and enjoy a final banquet (culinary performance art) in the Castle of Good Hope, a fortress that is the oldest surviving colonial building in South Africa. The schedule is so full that few speakers have time to visit the city’s famous townships and informal settlements, or explore other aspects of South Africa’s continued divisions. But Naidoo and his team aren’t interested in catering for such urban safaris but in putting South Africa’s best foot forward – in seeing their country compete on the international stage. The Economist claimed that, of the ten fastest-growing economies, seven were African. Design education is still in its infancy in South Africa and Naidoo considers Indaba a kind of university, exposing the country to global talent and ideas to help foster the local culture. Nevertheless, it is also a Do Tank, initiating a series of social and cultural projects; for example, a series of model homes built by Luyanda Mpahlwa in a squatter camp (see page 90) and a scheme to light another informal settlement. It is currently working to help found a new museum of contemporary art to be built by Thomas Heatherwick on the Cape Town waterfront (page 98). The line-up of speakers is eclectic. This year Juliana Rotich spoke about the problem of internet connectivity in Africa, particularly in the interior, which her company has tried to answer with the BRCK, a rugged modem. The photographer David Goldblatt gave a talk about his long career documenting apartheid. He used to work pro bono for lawyers, taking photos of racial abuse, and has recently embarked on the Witness project, returning people to the scenes of crimes. Jake Barton spoke about the political perils of designing the displays for the new 9/11 museum in New York; Clive Wilkinson about designing offices for Google in California; Dutch graphic design collective Experimental Jetset about the inspirations behind their rebranding of the Whitney Museum; and Mexican architect Michel Rojkind about his film museum and an intelligent, computerized football he hopes to persuade FIFA to adopt. Stefan Sagmeister, whose TED lectures have been viewed over 3 million times on YouTube, closed the conference. A seasoned performer (this was his second Indaba), he spoke about Happiness with all the gusto of a well-practised stand-up; think Kramer from Seinfeld. He is from Austria, which he pointed out was also the birthplace of Sigmund Freud, who made it his psychoanalytic project to transform “utter misery” into “common unhappiness”. Sagmeister showed a map depicting worldwide distributions of the emotion: “You’re supposed to be profoundly unhappy,” he commented, pointing to South Africa. The graphic designer showed images from his travelling exhibition The Happy Show, which overflowed the gallery spaces, infecting each museum with his witty visualisations – the elevator doors, for example, were decorated with a naked couple who appear to copulate as they open and close. Sagmeister is also making an accompanying film, for which he has exposed himself to meditation, cognitive therapy and drugs, and played clips here. These incorporated his active approach to typography with lots of exploding water balloons and bursting bubbles, spilling sugar cubes and raining coffee beans, used to spell out optimistic messages like “If I Don’t Ask, I Won’t Get”. He ended by getting the audience to sing a rousing hymn, with lyrics that scrolled on screen, karaoke-style. Brimming with inspiration, they sung with gusto. “Stefan always does the same shit,” it began: Seen it all before on Ted.com

Goldblatt’s photos documenting apartheid (Image: David Goldblatt/Magnum Photos) |

Words Christopher Turner |

|

|