Bruno Munari’s dizzyingly versatile body of work has always been hard to categorise. But he had the rare ability to alchemise the ordinary into something luminous, writes Rick Poynor

Words by Rick Poynor

In a photograph taken around 1945, Bruno Munari is on the telephone. Leaning back on a table, he holds the receiver to his ear. His expression is attentive but wry. He might be serenely fascinated by his caller, or he could just as easily be bored. In his other hand he lifts a pair of scissors to the phone’s twisted cable. One snip and the connection will be severed.

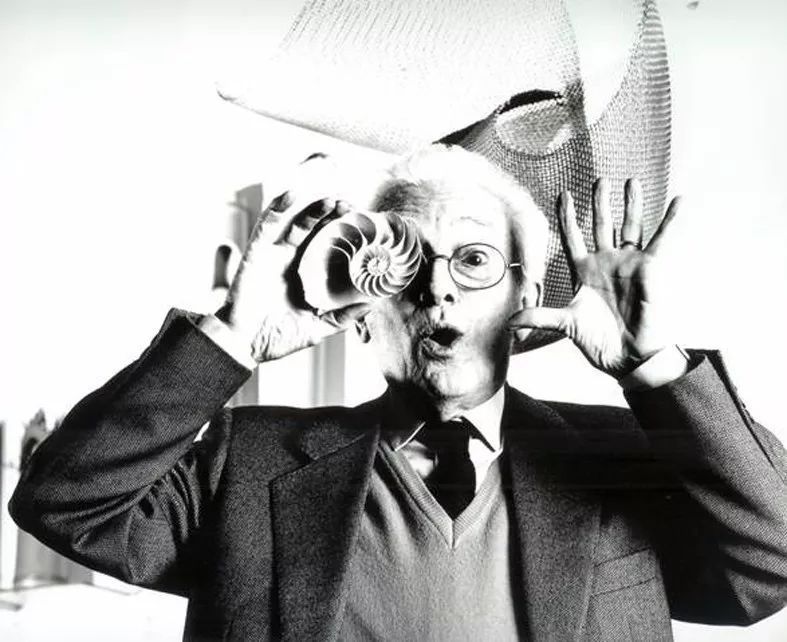

The artfully staged image conveys the essence of the great Italian artist and designer: witty, playful (always playful) and paradoxical, a new kind of modern philosopher of form and a tireless experimentalist. Munari made captivating use of photos to signal his discursive inclinations. In a famous series of pictures, available today as a poster, he struggles to get comfortable in an armchair, climbing all over the recalcitrant upholstery, contorting his body, and finally turning the chair on its back. It was a lesson in ergonomics conceived, around 1950, as a piece of comic theatre that anticipates performance art.

Since his death in 1998, Munari’s reputation has soared. In his lifetime he was highly visible, especially in Italy, yet somehow never fully celebrated as the major cultural figure he was, because his highly original and prescient output fell somewhere between art and design. We might now acknowledge that this interzone exists, since there are numerous examples, but institutionally and critically, where it counts, we still don’t entirely allow for it.

If the Munari exhibition mounted in Turin in 2016 were to come to London, would it belong in Tate Modern or the Design Museum? These temples are predicated on the idea that visual production needs to conform to the dictates of one discipline or the other. To place Munari in either would be too restrictive.

Design Icon: The Fiat Nuova Cinquecento brought driving to the Italian masses

Munari appears to have been untroubled by the issue, happy to conduct his researches in-between. He drew attention to the categorical dilemma in the title of his essay collection, Design as Art, rediscovered and reissued in English in 2008 after decades out of print. ‘The designer of today re-establishes the long-lost contact between art and the public, between living people and art as a living thing,’ he writes. ‘There should be no such thing as art divorced from life, with beautiful things to look at and hideous things to use.’

To this end, Munari unfurled a dizzying versatility. Alongside his sprightly critical writing, ever aware of the reader, he was a painter, a graphic designer, a deviser of three-dimensional objects (or are they sculptures?), an illustrator, a poet, an inventor and a teacher. He began as a futurist and cited Marinetti as an influence, though he quickly moved on. He was a dedicated constructor of ‘useless machines’.

These dangling aerial mechanisms, which pre gured the mobile, were his way of domesticating the ‘monster’ of technology. He was also a prolific fabricator of ‘unreadable books’. These delightful objects had no text whatsoever, concentrating instead on the formal and tactile treatment of the pages’ shape, colour and texture, with lines, threads and cut-outs.

Books were such a vital medium for him that his oeuvre was collected in a survey titled Munari’s Books, reissued in 2015. These include a book of his machines with humorous diagrams, his ABCs conceived for children (he was acutely sensitive to the young mind’s learning needs), his more formal texts about design, and a book of experiments with Xerox when the technology was still unfamiliar.

In one of these photocopies, manipulated with Munari’s customary lightness of touch, he gives himself five sets of eyes – that feels about right. When he got to grips with an everyday design challenge, he could alchemise the ordinary into something luminous. The Abitacolo (1971) is a bed, a climbing frame, a storage space, a shelving system and an endlessly adaptable den. It’s hard to imagine a child that wouldn’t love to own one. He could think like an angel.

This article was originally featured in ICON 179: May 2017

Get a curated collection of design and architecture news in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter