The Tank, as it was nicknamed, made its debut in 1936, bringing its Finnish designer a new international acclaim

Photography courtesy of Artek 2nd Cycle, TEN

Photography courtesy of Artek 2nd Cycle, TEN

Words by Joe Lloyd

The Milan Triennial VI in 1936 marks a point where European modernism seemed to be drifting into irreverence. In the authoritarian regimes of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, it had been violently rejected. The Bauhaus was forced to close. Elsewhere, it had lost its radical charge.

Enfants terribles had transitioned into near-establishment figures. In Milan, the already-garlanded Le Corbusier exhibited for France. There were contributions by painters Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Fernand Léger, almost three decades after Cubism had revolutionised art.

This atmosphere of slight stagnation was punctured by the work of one trailblazing Finnish couple, architects and designers Aino and Alvar Aalto. Aino took home both a Gold Medal for her Bölgeblick glassware and the Grand Prix for her exhibition display.

And Alvar introduced the world to one of his most indelible furniture designs: Armchair 400, nicknamed the Tank for its robust, thickset form (a different type of tank would haunt the next triennial, which closed on 9 June 1940 as Italy entered World War Two).

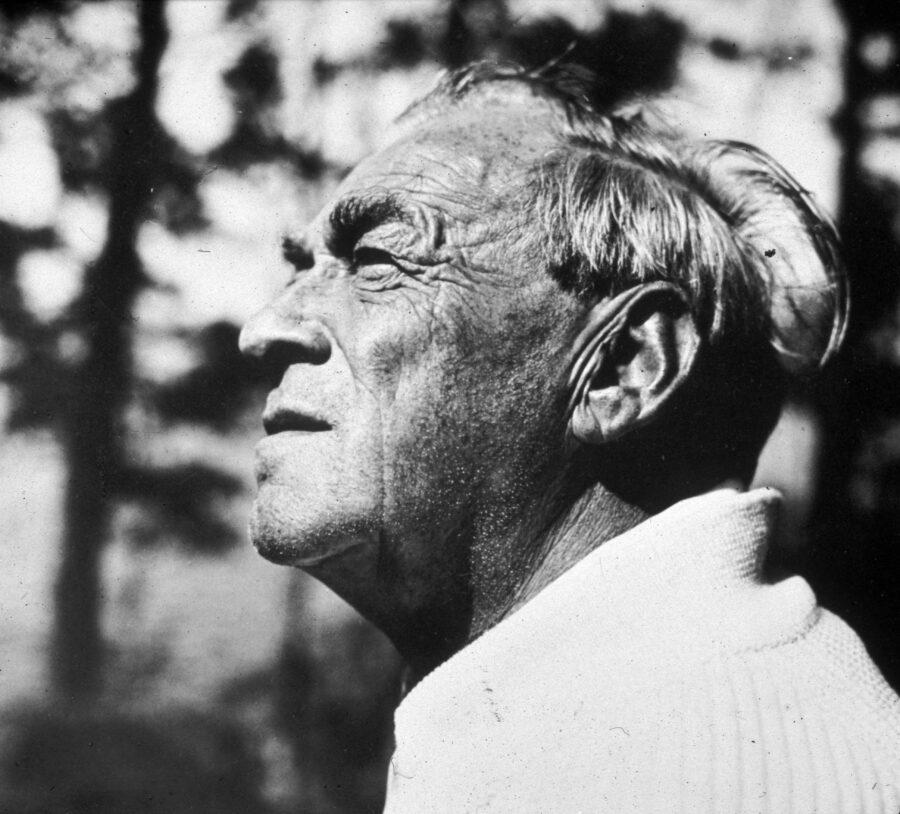

Photography courtesy of Artek featuring Alvar Aalto

Photography courtesy of Artek featuring Alvar Aalto

The mid-1930s found the Aaltos at a crux in their careers. They had already established themselves as leading lights in Finnish design. Artek, their production company, was founded in 1935. Alvar had pushed past the sepulchral Nordic classicism of his early career to design a series of functionalist buildings, including the Municipal Library in Viipuri (now Vyborg) (1927-35), the Turun Sanomat newspaper offices in Turku (1928-29), and the Paimio Sanatorium (1928-33).

This masterpiece of streamlined modernism spawned another: Armchair 41, the Paimio Chair (1931-32). Seat and backrest were fused as a sinuous plywood sheet, unfurling like a scroll and seemingly suspended between two loops of bent wood.

These works propelled the Aaltos from acclaimed provincial designers to the forefront of pan-European modernism. Their showing in Milan sealed the deal. The Armchair 400 took the basic structure of Armchair 41 — a single seat unit supported by two near-circular legs — but made it bigger, bolder and softer. It featured a sturdy cantilevered core, seat and backrest angled around 120 degrees from each other.

Photography courtesy of Artek

Photography courtesy of Artek

This upholstered seat has an extraordinary bulkiness, yet seems to float above the ground like a cloud. While the Paimio Chair’s armrests formed a closed loop with a near- horizontal top side, the Tank’s thicker armrests, made from bent birch lamella, gently curve for comfort. ‘It is the task of the architect,’ Aalto once said, ‘to give life a gentler structure.’ The Tank chair was a literal fulfilment of the adage.

Yet it was also a step away from the most astringent tenets of early modernism. From the start, the Tank’s upholstered unit provided an ample canvas for experimentation with pattern and colour. The most popular early variation was upholstered in zebra print, a vivid combination of black and white. By the end of the decade, versions were upholstered in numerous colours and patterns.

This process has continued to this day: one 2016 version features blue-dyed sheepskin and looks if it has been covered in the skin of Sulley from Monsters Inc; a 2017 collaboration with American streetwear band Supreme saw them upholstered in a bright red fabric that referenced Robert Indiana’s LOVE image. The Aaltos have often been credited with bringing humanism into modernism, breaking away from the theorising that preceded them. With Armchair 400, they also provided a space for individuation.

Read more in ICON 210: The Finland Issue or get a curated collection of architecture and design news like this in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter