|

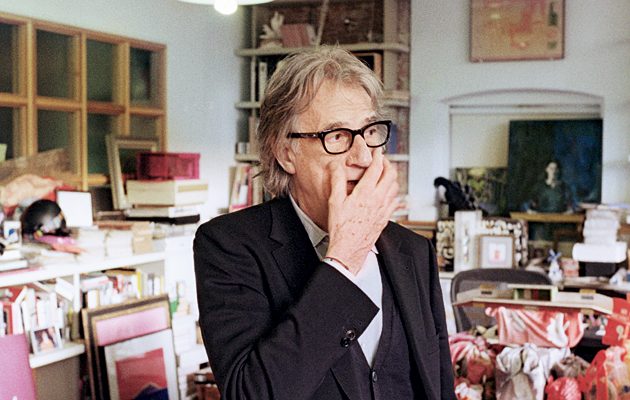

Paul Smith in his Covent Garden office (image: Dan Wilton) |

||

|

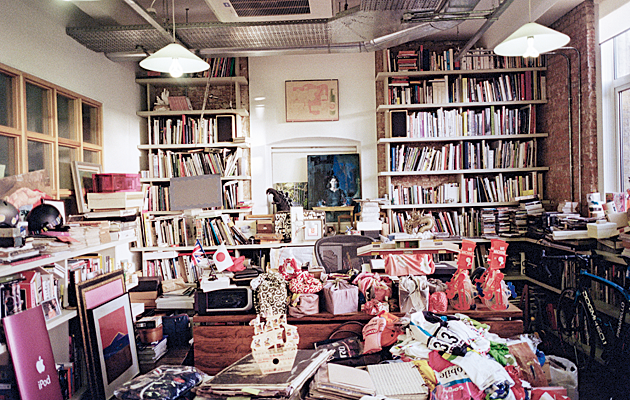

Since the launch of his first store in 1970, Paul Smith has mixed his fashion designs with the collection of curiosities that inspire them. He refers to this ever expanding hoard, which overflows his disorderly office and fills storage facilities, as The Department of Silly This article was first published in Icon’s June 2013 issue, which celebrated the magazine’s 10th anniversary. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this Sir Paul Smith‘s office is crammed with an impressive array of clutter. A flea market hoard of colourful curios covers every surface: there’s a phalanx of Mr Machine toys that walk along and whistle, another of spinning tops, a pile of old silkscreen posters from the Ivory Coast, a box of souvenirs relating to outer space. A keen cyclist, he has a number of sleek racers propped against bookshelves and, on the floor, there is a disorderly pile of cycling jerseys – on top, one signed by Bradley Wiggins. I am reminded of Picasso’s bohemian declaration, explaining the sculptures he fabricated out of rubbish in the 1930s: “I am the king of ragpickers!” Smith, now 66, refers to this cabinet of curiosities, from which he gets both pleasure and inspiration, as The Department of Silly. He comes to work at 6am every day and spends two hours here before anyone else arrives. “That’s when I really have the opportunity to enjoy the room,” he enthuses. His Pythonesque collection inspires him in tangential ways. “I might get the colours for my knitwear or socks from an old, badly printed book, or my speedometer collection has been really influential in my watch faces,” he explains. “It’s the influence of lateral thinking, colour, kitsch. I love the idea of mixing small and big, the kitsch and beautiful – a loose-fitting shirt with very tiny buttons, an embroidered cowboy shirt with a cashmere jacket.”

The packages contain bronze rabbits Smith started collecting things as a child from Sneinton Market in his home town of Nottingham – art deco jewellery, penknives and hat pins that would help form his taste. “My cash register in my first shop was an art deco cigarette box,” Smith remembers, “black with just a beautiful art deco design on top which I used for my first label.” The 1970 store was only 12sq ft and he filled it with more objects bought on his travels. He now has 350 shops around the world, with an annual turnover of £400 million. His ever expanding collection is still used to furnish these spaces – with 1960s posters, photography books, Japanese trinkets – giving them their signature, quirky, cultured cool. Smith admits to being something of a compulsive hoarder and, left to his own devices, he would soon be buried under an avalanche of stuff. His old, similarly unruly office in the attic above his Floral Street shop was abandoned in 2000 for larger premises in an old warehouse nearby. It has been left exactly as it was then: “I think it’s probably been eaten by mice by now,” he sighs. In just over a decade, Smith has packed the new space, to the horror of his assistants. They have begun to catalogue and archive his many things, some of which are valuable (gifts from Bruce Weber, David Bailey, Martin Parr), arranging them in the basement and another storage space in Nottingham on the kind of rolling shelves you find in museum vaults. “They’ve tidied it up,” Smith says of The Department of Silly, “and it’s all serious now, which is a real nuisance.” “How it all started, I’ve no idea really,” Smith muses. “I mean, obviously I like things. Somebody asked me to give a talk the other day about being a collector and I said, I’m not a collector but I do have large quantities of the same thing. And they said, that’s called a collector! But I replied that I’m more like a hoarder. I don’t know much about the bikes, watches or speedometers I collect – I just like and am fascinated by stuff.” As he and his eccentric tastes became more widely known, people started sending him things, which fill the daily postbag. “Today we got a poster of the Post Office Tower, with little windows that light up in the dark,” Smith laughs. “We got a bicycle cleaning kit, which is full of brushes and sprays; we got some eggs that look like owls. And that’s just in one day!” After a chance remark about how rabbits brought him good luck, he gets sent dozens of figurines, including antique bronze ones from a Japanese admirer that are neatly wrapped in boxes covered in silk.

Stamped objects from a mystery admirer “There is someone that’s been sending me things for 20 years, we don’t know if it’s a man or woman,” Smith adds, displaying an outsize fluffy chick that has been covered in stamps. Other things sent by this mystery person include a bowling pin, walking stick, frisbee, pair of water skis (which came separately) and tricycle, all buried under postage like Fluxus mail art. “It’s becoming like performance art now,” Smith says, when I make this connection. “The other week the postman arrived with an Austrian cowbell wrapped around his neck and it was clanging, and he just said, ‘That’s for Paul then, obviously’.” A Belgian girl called Margot has also been sending Smith things since she was 11. “Her first letter to me said, ‘I don’t like fashion but I like you.’ Now she’s 16 and at Christmas she thought it might be nice if I had a nativity.” Smith carefully opens a small box. “So she made one from peanuts. There’s baby Jesus – he’s lost an eye, I’ll just warn you. There’s the three kings with post-it note hats, two sheep, Angel Gabriel’s lost one wing. And we just met her – she came to my fashion show in Paris last Sunday.” He spins around and heads towards another shelf: “And then we’ve got the origami person, who sends lovely origami, and this is the nice lady from India who sends me interesting packaging …”

A sculptural birthday card from Apple’s Jonathan Ive An outsize, 3ft-high iPod is buried in junk. Jonathan Ive is a friend and sends Smith birthday cards that he makes himself in the Apple workshop. One of these is a white stack, piled in segments, each of which contains a letter to spell out P-A-U-L. “It took him three weeks,” Smith says, unpacking it on the table. The diminutive boyfriend of an architect who visited, and to whom Smith gave a suit from Japan, made him an exact model of the office in gratitude, each miniature object crafted out of Japanese newsprint. “When he came to visit, some of the things in the office had gone to an exhibition in Korea,” Smith says, “and he gasped, ‘The iMac’s gone!'” On one shelf is a collection of cameras, including a 1958 Rolleiflex that once belonged to his father. “He passed away when he was 94,” Smith says. “He was a founder member of the local camera club, and used to do his own developing and printing. He built a darkroom in the attic, so I was often up there with the chemicals, and he did a lot of trick photography.” He shows me a picture of himself, aged 12, floating on a magic carpet over Brighton Pavilion. His dad possessed an inventor’s ingenuity and, Smith admits, was also “a bit of a hoarder” – both traits Smith is proud to have inherited. “I hope that I’m child-like in my approach to life and my work,” Smith concludes.”I think in being child-like, as opposed to childish, you have that openness and you’re very curious.” He unlocks a suitcase to reveal a model railway and Alpine scene. “I famously brought this out in a meeting in Japan,” Smith chuckles, “and said that I was bored now: ‘I’m going to play with my train set’.”

Smith as a child in one of his father’s trick |

Words Christopher Turner |

|

|

||

The chaotic collection, with its heap of cycling jerseys