|

|

||

|

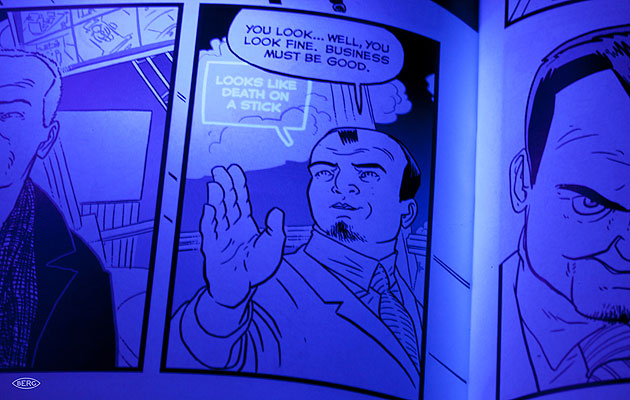

Now if you look through the Argos catalogue, there are thousands of products that are artificially intelligent,” says Matt Webb, one of BERG’s three principals. Not fully-fledged HAL-9000 artificially intelligent, but chip-smartened enough to be more than a dumb tool. And as chips have become more and more complicated they have also become massively cheaper, and as they have become cheaper they are embedded in more and more objects. So we’re increasingly surrounded by things that are … well, thinking. “The world is just full of non-human actors that we have to get along with. And that’s new, that’s different. How do we live in that world? We just have to figure it out as we go along.” That’s what BERG aims to do – figure out this new world of massive, ubiquitous complexity and develop new ways of living in it; to outsmart the chip-smartened world, or at least stay on its good side. “I tend to think of BERG as inventing next year,” says studio collaborator Warren Ellis, one of three science-fiction authors the group considers to be “giant uncles, or adopted parents” as Matt Jones puts it – along with Bruce Sterling and William Gibson. The future itself is being hammered out in a couple of overcrowded rooms in Shoreditch, east London – the very near future, that is, the future that really matters. “It’s a bit lazy [predicting] 15 years in the future. It’s frankly a doddle,” says Jack Schulze, BERG’s third principal. “If you go into a technology company and ask what’s going to be important in five or ten years time, they’ll have a big guess,” Webb adds. “If you say ‘what’s going to be important in six months’ time?’ that’s much harder, and it’s much more work.” BERG started life in 2006 as Schulze & Webb, which as the name suggests comprised only Webb – a scientist and author of a book on how the brain works, who was working in research and development for the BBC – and Schulze, who was completing an MA in interaction design. Schulze & Webb became BERG in 2009 with the addition of Jones, an architect by training who had been prominent in digital and interactive design since 1995. The name, in case you’re wondering, stands for British Experimental Rocket Group, professor Quatermass’ organisation in the radio and TV serials of the 1950s and 1960s. It was suggested by giant uncle Ellis. “The only brief was that it had to be small enough to be stamped on the bottom of a product,” Schulze says. Why Quatermass? “Quatermass is like a brilliant British figure because he’s got one foot in the future that he wants to lean into and get to but he’s also really pragmatic … he realises that everything he does has implications. He’s always about the wider ripple of a decision.” So what is being designed in this laboratory? BERG sits in a still-hard-to-define design field somewhere between media, service, interaction and product design. Its latest product is characteristically unusual: a comic book called SVK, written by Ellis and illustrated by Matt Brooker. BERG provided the high concept: the Special Viewing Kit, the little LED torch that comes with the comic book. The torch projects UV light on to the page, showing up hidden messages and thought bubbles. SVK’s hero can read minds, and thanks to the viewing kit, so can you – a charming trick that evokes both the joke-shop X-ray specs sold in vintage small ads and the age-old practice of reading comics under the bedclothes with a torch.

credit Dentsu & BERG This eagerly awaited Ellis/BERG co-production proved immediately successful in its own terms – it sold out within a week of launch – but was that all it was meant to do? Did they just want to make a comic book, or was there a more serious purpose? “The material I am obsessed with is business,” Webb says. “Building weird machines of people and capital and infrastructure to do creative things. I find it exciting to do that kind of stuff.” SVK was an experiment in business – “a way of channelling paper and batteries and lights from factories in China to warehouses in Kent and out to people’s houses”. It generated expertise and laid down infrastructure for BERG to make future forays into the physical – without going through traditional publishing, media or technology firms. So far BERG’s other products leaned away from the physical and towards the digital. It designed Mag+, a way for magazines to work on a tablet computer, before the iPad was even launched, a classic example of working in “next year”, developing concepts for devices that don’t quite exist. (Jones wrote about Mag+ in Icon 087, this time last year.) For offbeat advertising agency Dentsu, BERG made Immaterials, a film which uses light to show the invisible, sensitive fields generated by RFID devices like Oyster cards. That project also gave rise to Penki, an app that allows you to make light paintings with your iPad. The studio also built the Dimensions website for the BBC, a simple and addictive size-comparison tool that shows you, for instance, the extent of the Gulf oil spill if it was centred on your house. This will shortly be followed by How Many Really, which illustrates big and small numbers (like the death toll of the Black Death or the number of surviving tigers) by comparing them with your number of Facebook friends or Twitter followers. More recent is Suwappu, a line of networked collectible toys that frolic in augmented reality. What has made BERG successful in interactive design is the studio’s instinctive feel for how extremely new technologies like smartphone apps and augmented reality should look and work. They have a reassuring knack for the new idiosyncrasies of chipped, networked objects – what Jones calls the “giant Vonnegutian icebergs behind everything”. An iPod or a smart phone can’t really be understood as a “classic” object, because it doesn’t work without the whole structure of the internet behind it. “You can hide that and pretend that it’s an inert product, or you can choose to embrace that complexity, say that people don’t relate to this as a tool, they relate to it as a complicated thing, have a theory of mind about it,” Jones says. Imagining the product has a mind of its own needn’t make it intimidating – it’s simply a way of understanding its behaviour. “So what kind of mind should we pretend it has? Well, why not a puppy. Don’t try to be any smarter than that because you can’t be … but if you design as if people are trying to pretend that it’s a puppy, you think what kind of goals does this product have? When is it happy, when is it pissed off?” But the project that Jack and the Matts hold up as an exemplar of their working practices is one of the least successful. The Availabot is a little jointed plastic figurine mounted on a podium – it resembles the little dolls that dance and spasm when you press a button on their base, loosening the threads that hold them together. You plug it into a USB port on your computer and the plastic man lies there listlessly until the friend it represents logs on to an instant messenger programmer. Then, it springs to its feet. That’s all. “It’s a tiny thing that does nothing,” Schulze says. “Utterly stupid.” After five years of continual development, the Availabot still isn’t production-ready. Every aspect of this “stupid” desktop trinket, from its tiny low-power electrical motor to the software that allows it to talk to the internet, has thrown up engineering problems. They are steadily shaving pennies off the unit cost, but getting it out on the streets is no longer the primary aim. “We ran the models and figured out that it would never really be profitable,” Webb says, “but we could try and treat it like a space probe to find out how manufacturing works.” To BERG, it was obvious that networked, smart objects (even dumb ones like Availabot) were going to be the future, and they would have to be able to build them – and most importantly build them for the Argos catalogue price layer. “It’s like a biopsy of the modern world, taking a sliver from every stack of computing, manufacturing, supply chain and getting terrified by all of it and figuring it all out,” Schulze says. Schulze describes BERG as “a machine for our curiosity”. Rather than starting with a product in mind, or even having a product as an intended outcome, the studio has an omnivorous spirit of inquiry about the way stuff gets made. “We don’t really do the idea thing,” says Webb. “It isn’t like we sit around trying to have a concept, and then make it. We work differently from that, much more in the way that furniture or product designers work. We have what we call a material exploration, and some of those materials are not stuff.” Rather than working with wood or metal, the materials BERG explores are supply chains, consumer electronics, APIs, the habits of Chinese factories. When I arrive in the studio, Jones introduces me to Alibaba.com – a portal for manufacturers in the Far East to sell their products. You can order anything from buttons to chainmail hoods and diesel engines – in bulk, to your specifications. The whole modern Moloch of mass, cheap manufacturing is suddenly at your fingertips. There’s a chat channel – while browsing an object, a representative of the manufacturer can suddenly pop up and answer your questions about it. William Gibson – one of the giant uncles, who visited BERG’s studio a few days before Icon – said in 1993 “the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed”. Alibaba looks like a whole heap of future in one place, and BERG are the guys trying to figure out how to distribute it to us. Looking at Alibaba – and seeing Schulze, Webb and Jones’ fissile enthusiasm for it – BERG’s broader strategic aims become a little clearer. You can see the direction of all the probing and experimenting. The trouble with the modern world, the guys agree, is that designers are used by business to achieve the goals of business – not the other way around. And you have to have a market capitalisation of $10 billion or more before you get to do the really cool stuff. “For a really long time big businesses have commoditised creativity,” says Webb. “Is it possible to design to commoditise big business? To just have total freedom in what we make, and treat businesses like a machine?” They are feeling around the edges of the consumer-industrial complex, looking for its weak points, finding the secret ways in. The studio’s preoccupation, Jones, says, is “making people more curious about those sort of surfaces of the modern world … SVK is a small step into that universe, but there’ll be bigger ones shortly.”

credit Ivan Jones |

Image BERG

Words William Wiles |

|

|

||