|

|

||

|

BD Barcelona burst out of Franco’s Spain with an exuberance matched by their avant-garde designs. Forty years on, they’re still drawn to the bold and experimental The 43-year-old Catalan firm BD Barcelona finally opened a London showroom in Clerkenwell this May. On display were a number of designs inspired by Dalí paintings – the brass Leda armchair with its stilettoed legs, a taxidermied lamb with a small drawer and golden acanthus-leaf feet, and the striking Invisible Personage armchair, imprinted with the form of an absent sitter. There was also a scattering of other recent products, from the ‘radical sewing’ of the Couture armchair by Swedish studio Färg & Blanche, to the Aquário cabinet, a luminous combination of ash and glass by the Campana brothers. And, on the pavement outside, stood the famous Dalilips sofa, with Design Week revellers sitting to take selfies against its glistening red plastic. Yet the exhibit that best encapsulated the firm was a small, pink, penis-shaped vase: the Shiva by Ettore Sottsass, first produced in 1973.

Xavier Sust’s cardboard bedhead On first glance, BD might seem like one more firm buddying up with galleries and auctioneers to push design as the new art. Yet back in the 1970s its founders were energetic young architects – Pep Bonet, Cristian Cirici, Lluís Clotet and Oscar Tusquets all practised in Barcelona as Studio Per – joined by interior designer Mireia Riera. While working on bold shop interiors and ‘enthusiastic and risky’ housing projects with a touch of critical regionalism, they imagined the products with which they would like to fill them – the avant-garde fixtures, fittings and furniture that Franco’s Spain failed to provide. Tusquets recalls: ‘We’d meet up every night [and] tell each other the ideas we were hatching; when one of us got excited, we started developing it.’ Their aesthetic and academic urges lay with the architect-designers of Milan, such as Franco Albini, Vico Magistretti and, of course, Achille Castiglione, with whom they established contacts and friendships. So, in 1972, they launched Boccaccio Design, named after the nightclub patronised by the ‘Gauche Divine’, Barcelona’s left-wing intelligentsia. Its owner, Oriol Regás, was their original backer, financing both a small shop in upmarket Sarrià-Sant Gervasi and their early products. These were astonishing and eccentric, mostly designed in-house, and touched on any number of global design trends. The cautious modernism of the Franco regime was absent, replaced by the pluralistic approach of Archizoom or Superstudio. But there was also a degree of humour rare in Milan – incipient postmodernism alongside Pop flare – and a concern with self-production and artisanship, reacting against the mass-production of the consumerist ‘Spanish miracle’. The designs that resulted were often rudimentary and occasionally risqué, with nods to both past and future, from waterbeds and huge wedge-shaped cushions to cardboard cut-outs of ornate bedheads and chimneypieces – all ‘very crazy, very us, very young’, as Tusquets puts it. The Jipi lamp was intended to recreate the ‘intimate moment’ of draping a silk handkerchief over a bedside light before sex. The blocky, rearrangeable Negro sofas and Chinese Nest tables by Xavier Sust could have come straight from a Milanese studio – Cassina, Zanotta, Alesi and Driade were particular favourites. The alluringly flexible, worm-like Lampara Cuc in translucent plastic was intended for outside use but, with little allowance made for safety, production was soon abandoned.

The Dalilips sofa – first created with Dalí in 1972, it finally reached mass-production in 2004

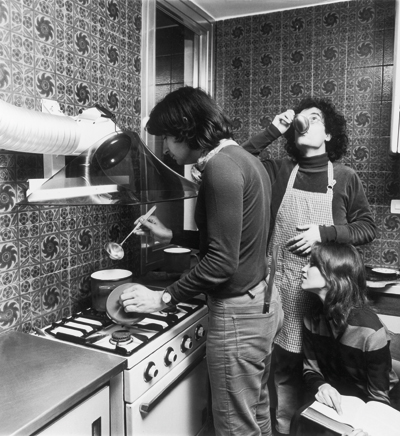

Oscar Tusquets, Lluís Clotet and designer Anna Bohigas demonstrating the plexiglas Campana extraction unit in 1973 The range and its graphics were stamped with the sensibilities of the time, but some products proved more durable in both physical and aesthetic terms. The group exploited contacts in Spain and beyond vigorously: Vittorio Gregotti was a prolific contributor, Ettore Sottsass was on board straight away with his Mettsass table. The greatest immediate success, however, was Álvaro Siza Vieira’s Flamingo lamp. A lightweight structure with a prototypical high-tech character at odds with much of the firm’s catalogue, it has been in production ever since. Another string to the firm’s bow was reissues. Gerrit Reitveld’s famed Red and Blue chair (chosen because it was easy to make) received a first ever reissue in 1972, alongside furniture by Mackintosh and a limited, somewhat perishable, edition of the Dalilips sofa – the ‘Salivasofá’ – a result of Tusquet’s close friendship with Dalí and their collaboration on creating a room at the Dalí Museum, Figueres, based on the artist’s 1935 painting, The Face of Mae West. Such ambition led to financial trouble and a buyout by the founders within the year, but a slight easing of the frenetic pace didn’t alter the eclecticism. The key concept was that, without the burden of a factory, the newly renamed BD Ediciones de Diseño could act as a publisher rather than manufacturer of design. It could search out the most suitable factory for any product, without constraints of material or technique, of style, or even of period, yet retain an unusual degree of control from idea right through to distribution. Given the founders’ architectural backgrounds, an increasing number of fixtures, fittings and accessories began to appear in the catalogue: hooks, handles, bins, television trolleys, umbrella stands and bike racks. There was even a transparent plexiglas extraction unit, the Campana, to be placed at a low height to increase performance while maintaining visibility.

|

Words John Jervis

Above: The Shiva vase by Ettore Sottsass (1973) |

|

|

||

|

Javier Mariscal’s Dúplex stool, first created for a Valencian bar in 1981, and produced by BD Barcelona since 1983 |

||

|

Much of the firm’s work in the 1970s, such as the classic Hialina and Hypóstila shelves in extruded aluminium, was designed in-house, and adopted a sparser style than their first offerings – as Tusquets jokes, ‘Later on, we saw sense.’ The famous Catalano outdoor bench, with its innovative steel mesh and high back, pushed the firm into town squares across Spain, while a much-copied vertical mailbox ensured its presence in the country’s offices and hallways. Reissues continued apace, including a hugely successful series of brass fixtures and fittings by Gaudí. Yet the triumph of postmodernism did not go unnoticed – Javier Mariscal’s Dúplex stool was an undisputed and early classic, while Tusquet’s hugely successful Varius chair proved that it was possible to introduce postmodernism to the workspace. In 1979, BD Ediciones started hosting exhibitions in an expanded space in the eye-catching Casa Thomas – it was undoubtedly the Spanish firm with the highest profile in the 1980s – but a certain complacency crept in. Catalogues boasted a few too many slim light fittings in a thin postmodernist style, failing to capture the exuberance of Memphis, or of their own youth. Self-congratulatory manifestos flourished, describing the firm’s style as one that ‘is shared with architectonic composition, genius and invention, and cultural and historic references … BD has been the elite of Spanish design’.

The Gaulino chair by Oscar Tusquets, originally released in 1987

Eduard Samsó’s Mirallmar mirror, designed in 1991 for the Barcelona Olympics An awareness of their limitations lead to an increasing number of collaborations with Spanish designers, but the best designs were often initiated elsewhere: the Olvidada lamp by Pepe Cortés, released in 1984, had been designed back in 1976; Eduard Samsó’s Mirallmar mirror was created for the Barcelona Olympics. Despite successes such as Tusquet’s own Gaulino chair – his first project in wood, inspired by Gaudí and Carlo Mollino – the confidence of previous decades had ebbed away. The challenge presented by the maximalism of the new Italian and Dutch design in the late 1990s – of Capellini, Moroso, Kartell, Cassina and Droog – was first confronted with real guts in 2000 with the arrival of Ramón Úbeda as artistic director, who recalls ‘the sensation of vertigo when I was appointed: it was clear that the design scene was changing and there was a need to look beyond’. The launch of Ross Lovegrove’s futuristic, biomorphic BDLove collection, as well as Argentinian designer Alfredo Häberli’s Happy Hour bar furniture, were vital in this regard, although both were met with incomprehension from many in the Spanish design community at the time.

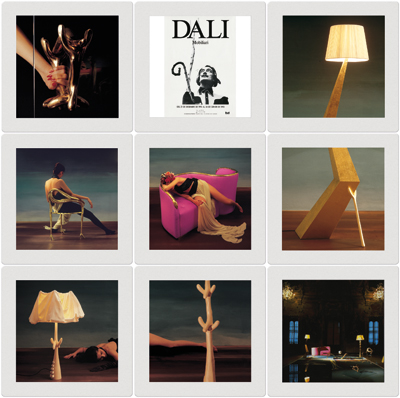

A selection from the 1991 collection of Dalí’s designs, including the Leda chair, the Bracelli and Cajones lamps, the Rinoceróntico door handle and the Vis-à-Vis sofa The real breakthrough came in 2006, however, with Úbeda’s patronage of an exciting new talent from Madrid, Jaime Hayon. His Showtime collection was bold and unexpected, placing outdoor techniques inside while mixing the industrial with the handmade. It helped to launch Hayon on the international scene, and ensured that the newly renamed BD Barcelona was again perceived as a vital player by designers and audiences. Since then, work with Konstantin Grcic, Doshi Levien, Martí Guixé, Neri & Hu and the Campanas has flowed, an impressive roster for any design firm. Perhaps the real challenge will be to ensure a USP for BD Barcelona that separates it from competitors employing the same designers. All collaborators are certainly given a singular freedom to experiment in materials and techniques, investing results with ‘an emotional and artistic component’, as Úbeda puts it. Art has proved one fruitful avenue, dating right back to the raunchy Hermaphrodite cushion of 1972 by Catalan contemporaries Eduardo Arranz-Bravo and Rafael Bartolozzi. This approach really took off in 1991 with a collection of ‘the most viable and commercially appealing of Dali’s furniture designs’, such as the Leda chair and the Vis-à-Vis sofa. At the time, Tusquets wrote of these works, drawn from Dalí’s paintings and sketches, that ‘we kept reminding ourselves that we were producing furniture and not pieces for the art market’.

The chrome BDLove 2.0 bench (2010) by Ross Lovegrove, created eight years after the original BDLove series Today, such qualms have been pushed aside by commercial realities. Limited editions have become the norm as the Dalí offerings become more esoteric, and have proved a powerful tool in boosting sales and visibility in the new markets of the Gulf and China. This approach goes hand in hand with selling such projects as exemplifying artisanal skill. Tusquets regretfully admits that ‘we have lost the fight over mass production’. Image has replaced functionality or ease of production as the primary concern, and even such classics as his Hypóstila shelving fail to find export markets, lacking the required ostentation. But one hopes that BD Barcelona does not end up, of necessity, specialising just in design art, abandoning a more free-wheeling past when it experimented with the possibilities of domestic space and invented new typologies in industrial production. Standing on the margins of European design and politics long gave BD Barcelona a curious freedom, ensuring a remarkable diversity and vigour over four decades, which ranged across markets, materials, styles and periods. Pressures, whether from Ikea, design rivals or architectural suppliers, may have constrained their exuberance, but as Úbeda puts it, ‘We try to work using reason, though at times the heart wins, overcoming the risks. That is in our DNA.’ With this ambition, and their astonishing back catalogue, BD Barcelona should flourish in years to come. |

||

|

The 2016 iteration of the Showtime armchair, sofa and Poltrona hooded chair, created for the collection’s tenth anniversary |

||