|

Jake Barton’s exhibition design for the 9/11 Memorial Museum is dominated by voices: harrowing witness accounts, the shared remembrances of victims’ families – and the ongoing debate about what precisely the museum should be for How do you make a museum for an event that isn’t over yet, and whose impact we don’t understand yet, and whose theme hasn’t been digested yet by society?” Coming from anyone else, such a question would be rhetorical, but for Jake Barton, it was a genuine quandary. Eight years ago Barton’s studio, Local Projects, was hired to help design the exhibits for the 9/11 Memorial Museum. From the start, there were conflicting opinions on how to proceed – and whether to proceed at all. When Barton’s team began working on the project, they attended several listening sessions, called the “Conversation Series”, which included financial stakeholders, residents, survivors, family members, historians and museum experts. “At the same time as you’d have people standing up and saying ‘It’s too soon,’ the next person would pop up and say, ‘What’s taking so long?'” he recalls. Things got more complicated when it came time to develop and fill the museum. “We would ask different members of the community what we should put in – one person would say, ‘Don’t make it so difficult that I would get retraumatised,’ and another would say, ‘I lost my loved one and believe this exhibit should be hard, it should be as hard for other people to go through as for me.’ Trying to judge that mental spectrum is not easy.”

The museum pavilion, designed by Snøhetta, and Michael Arad and Peter Walker’s memorial pools Despite the hurdles that the Conversation Series seemed to present, discussion has always been both the starting point and the goal for the museum. In its opening pitch, Local Projects noted that at the edge of the core audience were almost opposite groups. “You have survivors, or family members, people who know more about the event than any historian. They ran out of the burning buildings for their lives, witnessed things first hand,” Barton explains. “And then you have people who know nothing about the event, young adults aged 14 or so, with no direct memory, who might not know anything about it. That’s the nature of human memory, it goes really fast.” To talk to both groups, Local Projects suggested using the stories from one to engage the other. The opening gallery sets up this dynamic. As visitors descend a ramp (meant to evoke the ramps set up both for the original World Trade Center construction crews and the rescue workers who entered Ground Zero after the attacks), they pass floor-to-ceiling panels with projected snippets of text corresponding to audio recordings that turn out to be remembrances of 9/11. Recorded by 417 people living all over the world, who remember witnessing the attacks either in person or on television or radio, the range of accents is resonant, though the story they tell is painfully familiar. Similar phrases echo one another – “It was a beautiful day” and “mayhem” are two that stand out – and the panels

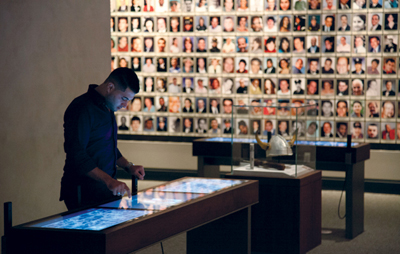

Table displays and photographs of the victims Though a staggering number of artefacts are on view – ranging from the grandly symbolic, such as a battered fire truck, to the startlingly personal, including a pointe shoe owned by one of the victims – recorded voices carry the bulk of the museum’s historical exhibition. The voices you can hear are often in the form of heartbreaking messages left on cellphones and answering machines by victims. Each of the four attacks – on the two World Trade Center towers, the Pentagon, and United Airlines Flight 93, the plane that went down in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania – is given what Local Projects calls an “audio alcove” that tells the story of that particular sequence of events. Another is dedicated to those who fell or leaped from the towers’ windows. The alcoves are separated from the main path of the exhibition to allow viewers to choose what to experience – and the audio recordings are quite harrowing. One reason for the focus on audio is practical: there is a lack of visual documentation of the attacks as they transpired. “There were three or six photographs taken from inside the towers,” Barton says, and a bit of footage of the lobbies. When visitors aren’t hearing from the victims, they are listening to witness accounts or, in the In Memoriam exhibition, to memories of the some 3,000 victims recorded by friends and family.

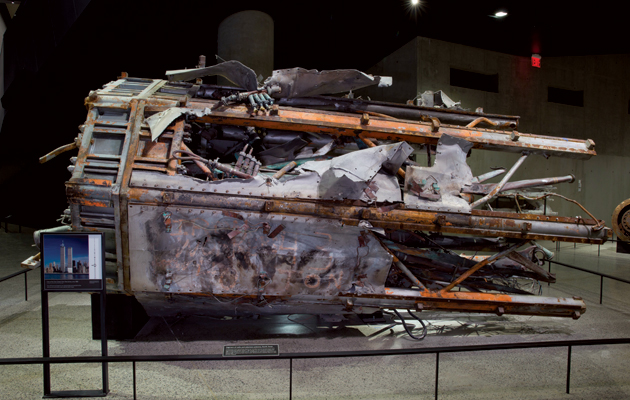

Fuselage fragment from American Airlines Flight 11 There is also an opportunity to share. While the historical and memorial exhibitions are about listening, a separate chamber with individual recording studios, called Reflecting on 9/11, moves towards telling. “You can share a memory of someone, or share your memory of 9/11. This allows people to think and talk about some of the more challenging aspects. That was a buffer … to be a technique that allows the museum to age and evolve with the event itself.” But the emphasis on storytelling has another purpose – to highlight the individuals who died in the attacks. “The museum tries to make points about the nature of terrorism but not overtly,” says Barton. “It is not a straight museum telling the story, but has memorial written into its core mission. If you think about terrorism there’s a strong argument to be made about the horror of abstraction, that to the people who flew planes into these buildings, the people in there weren’t people, they were just an idea, a notion that they hated and wanted to destroy. We spent a lot of time trying to make it what you would think of as a wake rather than a funeral. It’s about these people as little league coaches, or their favourite jokes, or what they were like standing up at their best friend’s wedding.” Barton’s background made him the perfect candidate to process and handle the number of personal voices involved in the museum. Early in his career, as a designer of interior architecture for museums, he noticed that visitors knew as much if not more than the curators about certain topics. “If you’ve ever been to a car museum,” he says, “the people who inhabit the floor just know everything about this Mustang, but even in a World War II museum, you have veterans going to these museums and sharing their own stories, but only with the people they go with.”

A salvaged trident and other artefacts from Ground Zero Influenced by playwright Anna Deavere Smith, who works on collaborative theatre pieces based on real-life events, such as the Rodney King beating and subsequent trial, by interviewing people who were involved or invested in the event, Barton began to wonder if a stronger sense of community and collective experience could be cultivated from museum audiences. “I was working on an exhibition for Intel about how the internet worked,” he says, recalling his eureka moment some time around 1997, “and I remember looking at that famous network map of the internet and thinking, ‘This is how it works.’ It occurred to me, at that point when the internet was being used as an information dissemination network, you could create feedback loops inside these exhibition experiences.” Not everyone was so open to the idea – the head of Barton’s firm said, in response to one of his ideas for an exhibition for Unicef, “What do we care what visitors have to say?” – but Barton saw an opportunity, quit his job and got a degree in art and computer science at New York University. He later went on to join StoryCorps, designing oral history booths for a project that is collecting thousands of personal stories and archiving them at the Library of Congress. This project has hardly been smooth sailing, however. For some, the museum’s memorial aspect, and the emphasis on grief and mourning, is problematic. It prevents catharsis, and more importantly, forgiveness. Critics have already pointed out the absence of any feeling of “freedom” at a plaza purportedly celebrating the concept. |

Words Claire Barliant

Images: Jin Lee, Amy Dreher |

|

|

||

|

An antenna from the north tower of the World Trade Center |

||

|

Blue-vested attendants roam around, more like corporate guards than helpful docents, and the security check at the museum’s entrance, which includes a full-body scan, almost feels intended to remind visitors of the experience of boarding a plane, insinuating a feeling of vulnerability and danger. Though the 9/11 Memorial Museum doesn’t actively promote fear of the other, it does little to subdue it. In Salon.com, Patrick Smith pointed out that the hijackers are not identified as terrorists, but “Islamic terrorists”. There have been complaints that the museum doesn’t make a significant effort to distinguish terrorism from Islam, and museum visitors were quoted in The New York Times describing the museum’s treatment of Islam and terrorism as “clinical” and “light”. Barton is philosophical about such criticisms and is able to frame these disagreements positively. “The project had and continues to have the role, and I would frame it as a civic role, of being a lightning rod for controversies. In a democracy, public memorials are a site maybe not to resolve but to have arguments that lie dormant in the general public. So, with the case of the 9/11 museum, there were so many unresolved feelings on so many levels, it’s part of the process that it’s there to help flush out and catalyse conversation around the event.”

The reconstructed shopfront of Chelsea Jeans, thickly coated with ash A seven-minute video about Al-Qaeda, narrated by news anchor Brian Williams, underwent several revisions, he says, in order to present a factually accurate picture of the geopolitical situation that gave birth to the extremist group. Nevertheless, it is the only time an outside “authority” is heard, and in this case it is telling a story that is fundamental to truly understanding the event. As I tried to follow the narrative, I noticed most visitors strolling by what seems to be the museum’s most obviously didactic display. Perhaps more troubling was my experience in the audio alcove devoted to Flight 93. Here, I held my breath listening to a flight attendant reassuring her husband on a voicemail message that she was currently safe, before she dissolves into tears to let him know how much she loves him and their family. As the story unfolds, both in audio clips and on a screen that presents a very effective timeline of the event, I found myself hoping that the passengers, who plotted to overthrow the terrorists manning the plane, would win. It felt like an action movie, and even though I knew the outcome, I couldn’t help but wish that perhaps this one time it would end differently. The cinematic experience was part of the design, Barton explains, in response to my recollection of this unsettling feeling. “The historical exhibition is cinematic, it drops you into an event, tells the story of the first day, then retroactively tells you about the roots of the event, looking at Al-Qaeda, then the aftermath. It is both unorthodox and cinematic in terms of the way you would tell that story.” My response to the Flight 93 alcove is exactly what he and the other designers hoped would happen. “The fact that you, as someone who went to the museum, might have empathised with the people, at least to me that says you were inside that story in a compelling way. And that is a good thing.” This article was first published in Icon’s October 2014 issue: Museums, under the headline “The memory collector”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

||

The underground Foundation Hall is built against the original concrete slurry wall