words Beatrice Galilee

“Here is Athena,” says Dimitrios Pandermalis, director of the New Acropolis Museum presenting part of a 2,500-year-old statue in the top floor of his new building. “Unfortunately her breast is in London.” He looks at me pointedly as we take a tour of the Parthenon gallery. “Here is Poseidon’s torso,” he continues. “His chest, of course, is in London.” Pandermalis has been waiting 25 years for a chance to present his case for the return of the Elgin marbles. His effort to repatriate the parts of the frieze that survived the rise and fall of the Hellenic and Roman empires, and the invasion and occupation of Goths and the Ottoman Turks, but not the perseverance of Lord Elgin, who shipped them back to London in 1815, has so far come to nothing. Providing a purpose-built space for the marbles, with plaster replicas standing in for those in London’s British Museum, shows they have the facilities to look after them. The Greeks are gambling €190m that, left with only a moral position, the British Museum will buckle.

Walking towards the site through narrow streets lined with six-storey apartment blocks with faded awnings and laundry hanging over their dusty balconies, I feel almost nervous. A museum to hold the 4,500 artifacts taken from the site of the Acropolis is a mighty task; it has to be a tribute to and in some ways an extension of the most famous building in the Western world, which stands just 300m away. It is also, potentially, a poisoned chalice: it has to provide a space grand enough to hold the marbles, but one that will still work if they never arrive. How will Bernard Tschumi, the Swiss-born architect, theorist, educator and writer, famous for his deconstructivist theories on agitated spaces, deal with the historical, local and international tensions this museum presents?

“I’ve been thinking a lot about it,” says Tschumi, speaking from a departure lounge in JFK airport. “The architect of the original Parthenon was Phidias, the sculptor. I thought, you cannot do something like a Phidias next to Phidias. Then I thought about the mathematician Pythagoras who was not building but writing theorems. I wanted our building to be like a theorem. It would be a very elegant and beautiful demonstration of an idea. And that is what I tried to do.”

Tschumi’s strategy turns the museum into a contemporary abstraction of the Parthenon. He wants visitors to see the sculptures and artifacts in a space with the grandeur in which they were originally displayed. He takes literal, physical references from the Parthenon, such as columns, volumes and views, and replicates them in the museum in steel, glass and concrete to provide a narrative of sorts. All the while he has tried to solve the very tangible problems that the site and the museum present.

The first competition to build a museum for the treasures of the Acropolis was held in 1975. The entries came from all around the world, but much to the disappointment of the applicants – including a young Zaha Hadid – no winner was chosen. Another competition was held in 1979, and then another in 1989. When a winner was selected (a peculiar cyclops-eye design) the project was abandoned because archaeologists discovered a set of Roman ruins on the site. These were then incorporated into the fourth and final brief. Swiss-born, New York-based Bernard Tschumi, former dean of the Columbia School of Architecture, took the prize in 2000, beating a shortlist including Daniel Libeskind. “His design was simple, but powerful,” recalls Pandermalis.

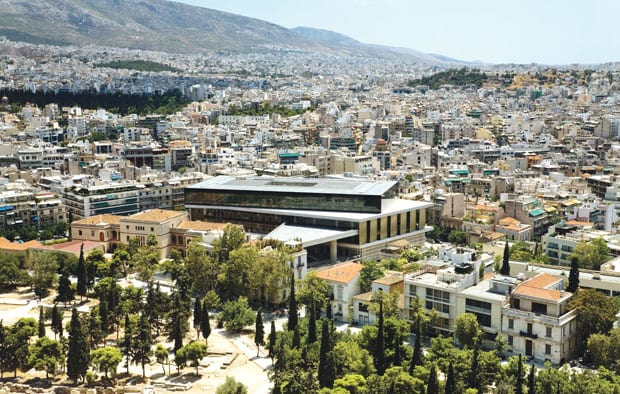

Tschumi’s vast 21,000sq m museum is crammed into a site south-east of the Acropolis, flanked by tall apartment blocks on narrow streets, a neo-classical office building, coffee shops and a metro station. This is a building that can swallow the Parthenon whole with room for a temple or two more, but unlike that pale marble edifice, it’s not on the top of a hill looking over the city – it’s in the midst of it. Athens is not like Rome with grand palaces or monumental architecture in the public arena. It’s a difficult, messy city where buildings fight for space above the layers of history. The museum feels like it’s blind to those surroundings and focused solely on that building on the hill.

The entrance is covered with a huge triangular concrete canopy that points commandingly in the direction of the Parthenon. This quite dramatic, deferential gesture has, however, been compromised by the presence of three Art Deco-era buildings that have resisted demands for demolition and stand obstinately and awkwardly in its line of sight. Both architect and client clearly imagined that these structures would be gone, and their presence stands for much of the visible tension between this building and the city around it.

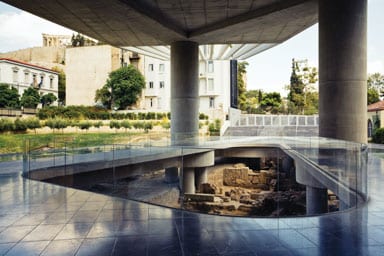

What the building does engage with is the past; the remains of a Roman city – brick baths, houses and streets – informed its orientation. The whole museum is lifted over the ruins on enormous concrete columns, and visitors can wander among them in certain places, and throughout the lower floor of the museum they are revealed beneath glass floors. The ruins sit easily amid all the reinforced concrete but this is a rather functional treatment. There is none of the delicacy of Peter Zumthor’s enchanting Kolumba museum or the calm of Carlo Scarpa’s Venice museum, the Querini Stampalia, both of which incorporate ancient remains into the very fabric or soul of their design.

The first explicit bit of Tschumi’s spatial storytelling takes place in the ground floor atrium. The volume of this opening space is the same as the interior of the Parthenon temple. This opening void is flanked by glorious objects on plinths and concrete sound-absorbing walls. The floor gradually rises, representing the hill of the Acropolis, and culminates in a set of grand steps which lead to the first-floor gallery.

This level is an unexpected forest of columns, marking the end of the story of scale and grandeur and the beginning of the very literal story about sculpture. Breathtaking statues from the height of antiquity are laced between a forest of thick dusty matt concrete columns and lit by a wall of floor-to-ceiling south-facing windows. The soft concrete is not structural, it serves to recall the purpose of columns and absorbs some of the reflection from the pale marble floor. The effect shows an unexpectedly sensitive side of the architecture that indulges in light and materiality rather than the slightly didactic narrative of proportions and scale.

The final chapter and the museum’s main event is the top floor Parthenon gallery. The entire room – a low glass box – departs from the rest of the building and swivels to be parallel to its subject. This feels like a rather academic, slightly mundane gesture. You’ve already seen the Parthenon from so many other places in the building by now that it doesn’t seem to add anything.

In the centre of the room, behind a colonnade that again mirrors the one around the Parthenon, the frieze will be displayed at eye level, around a central core and presented in its original order. However, when we are here much of what I can see is cast in bright white plaster, indicating those items that currently have a London postcode.

In this museum, Tschumi has not just borrowed ideas from the Parthenon; he has shipped them in wholesale. It’s as though this once radical architect has been completely cowed by the weight of his task and the proximity of his subject. It’s certainly not a shy building – it is highly imposing – but it’s so focused on the Parthenon that it doesn’t seem to belong to everything else around it. Ironically, it could be anywhere.

Of course, the Parthenon is an intimidating touchstone. Contemporary architects are still trying to outdo it. Just last month, Wolf Prix gave a lecture at the World Architecture Festival in Barcelona in which he showed the Parthenon and declared that while it covered spans with an optimum number of columns, his own buildings could cover far more ground with far fewer columns – as though his work had evolved beyond it. The comparison was brilliant and ridiculous for the same reasons. Perhaps Tschumi could have shown a touch of that irreverence.

For all its antique treasures, without the marble frieze it has been built to contain, the building is an empty vessel. But it is hardly toothless. If the Elgin marbles wind up in its top floor gallery, it will be a success. If not, and white plaster replicas remain, then the building will simply continue to exist as political collateral. How it will be remembered will depend on what happens next.

All images: Christian Saltas