words Julian Worrall

Having an entire country as your sandpit often gives tyrants delusions of architecture. North Korea’s dictator has even put his theories on paper. Julian Worrall found a copy.

The dictatorial personality often displays an obsessive fascination with architecture. Architecture promises compensation for the insufficiencies of worldly power; it offers something concrete. In the 20th century, no dictator worth his salt neglected architecture. Hitler tinkered with his model of Berlin even as the Red Army closed in; Mussolini imagined a second Imperial Rome in ferroconcrete; Saddam Hussein built palaces on the banks of the Tigris. Most of these dreams are now ruins, and the dreamers are mostly dead. But one old-school tyrant lives on in his fortified private dominion – Kim Jong Il, North Korea’s “Dear Leader”. What grand architectural visions fill his cities and his dreams?

In 1991 he wrote On Architecture, a 170-page treatise detailing the nature and role of architecture in the North Korean state. Available in English in obscure corners of the internet, it presents a fascinating insight into the peculiar imagination of someone for whom society has the malleability of an intricate scale model.

The document has four sections: Architecture and Society details architecture’s significance and role; Architecture and Creation sets out design principles; Architecture and Formation discusses aesthetic theory; and Architecture and Guidance covers the architect’s qualifications. Much of the content is unsurprising. Stock soundbites from the Marxist-Leninist playbook are sprinkled across every page – architecture must maintain a “revolutionary outlook”; architects must display “party loyalty” and avoid “decadent reactionary bourgeois” design. Architecture, like everything else in the totalitarian state, must be “revolutionary”.

What is surprising is the proliferation of statements that wouldn’t be out of place in any introductory course on architectural history and theory. For Kim Jong Il, architecture is a “product of social history”; it is a “mixed art”, in which “variety” and “harmony” are essential; and it must “combine national characteristics and modernity appropriately” – a sentiment not far from critical regionalism. There are detailed discussions of the relation between utility and beauty. The work even anticipates the bureaucratic jargon of “creative industries”: architects in North Korea are “creative workers” too, except that here the basic creative principle is to “regard the leader’s plan and intentions as absolute.”

This all culminates in the formulation of a theory of “juche architecture”. Juche is the central idea of the North Korean form of isolationist communism. Roughly translated as “self-reliance” and “independence”, juche was an invention of Kim Jong Il’s father, Kim Il Sung, and has political, economic and military aspects. Kim Jong Il liberally reinterprets these attributes within the field of architecture as meaning “people-centred”, in other words devoted to meeting “the masses’ aspirations and demands”. These “demands” are fairly elementary, namely “convenience, cosiness, beauty, and durability”. Heady stuff this, though hardly unique to North Korea, or particularly revolutionary. Kim’s claim that juche architecture’s “content is socialist, and its form is national” is standard for the popular revolutions of the 20th century.

An example of what this amounts to in formal terms can be found in the Grand People’s Study House, a building of a vaguely neoclassical plan surmounted by 34 traditional Korean “saddle roofs” and finished in green tiles. Here, as elsewhere in Asia, national character is all in the roof. But Kim goes on to argue that “the real beauty of architecture lies not in its external form, but in its content”. Could this be, in 1991, an anticipation of Rem Koolhaas?

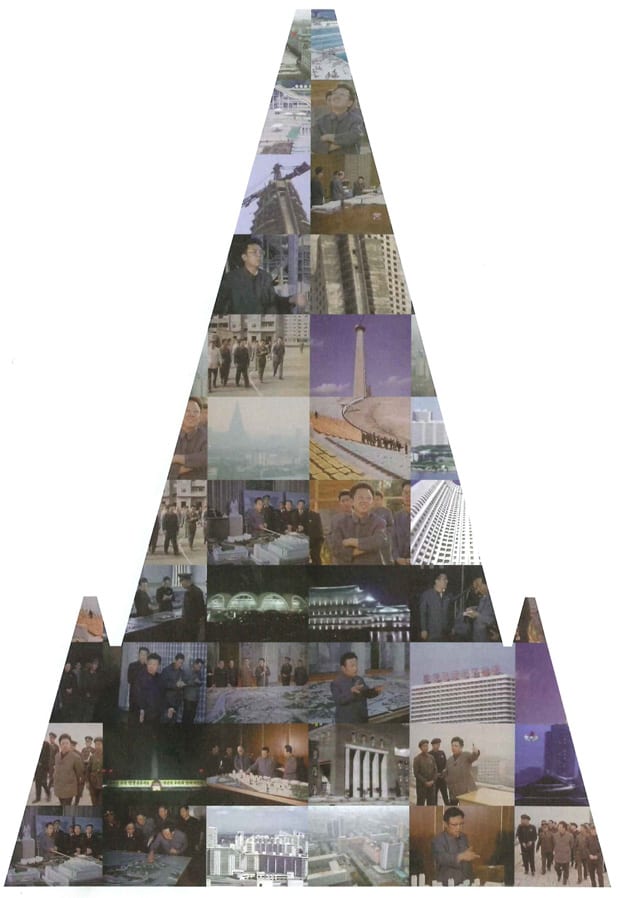

Kim shares the fondness of his fellow dictators for symbolic excess, as symbolic gestures provide “the best visual and lasting means of conveying the leader’s achievements and his greatness to posterity.” Whole chapters are devoted to monumental design and symbolism. Pyongyang, according to Kim the most beautiful city in the world, and his personal sandpit, has been showered with monuments. A statue of Kim Il Sung adorns a hilltop; an Arch of Triumph straddles a major boulevard; the Tower of the Juche Idea, resembling the Washington monument, sits on a central axis. But probably the most ambitious monumental structure in Pyongyang is the 105-storey, 330m Ryugyong Hotel. Unfinished and abandoned since 1992, its pyramidal form has towered over the city for nearly two decades, yet it doesn’t rate a mention. The symbolism here doesn’t play well for the revolution.