words Sean Dodson

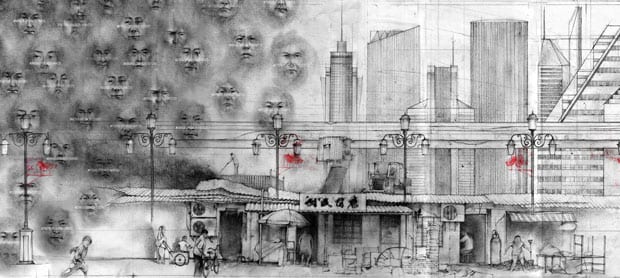

Shenzhen, China’s youngest city, has become a testing ground for a vast, integrated network of face-recognising CCTV and ID cards. And now the system is going global, says Sean Dodson.

Illustration Minho Kwon

Shenzhen has long been China’s social laboratory. Some day very soon Shenzhen will overtake London to become the most surveilled city on earth. Over the past two years the city has been busy installing 200,000 CCTV cameras, many in public places disguised as lampposts. All net cafes in the city are already under the watchful eye of CCTV, as are restaurants and other places of entertainment.

By 2011 the city is estimated to have increased the number of cameras tenfold, making London’s 500,000 cameras seem modest by comparison.

But it is not just the number of cameras that will make Shenzhen’s surveillance system the most complete yet built. Each of the city’s cameras will soon be connected to a single, China-wide database – an unblinking system capable of tracking and identifying everyone within its range.

“Old-style censorship is being replaced with a massive, ubiquitous architecture of surveillance,” according to Greg Walton, a British human rights activist based in Tibet. “Ultimately, the aim is to integrate a gigantic online database with an all-encompassing surveillance network.”

Golden Shield began life as the “great firewall” of China – a way for the party elites to exercise control over the nascent internet. But in recent months Chinese authorities have booted Phase II of the project. The security cameras atop Shenzhen’s lampposts are but the public face of a much deeper, more pernicious, form of surveillance. The cameras will be integrated with several other forms of monitoring – internet, mobile usage, GPS data and face-recognition software – so that they will eventually be able to identify each and every one of China’s 1.3 billion citizens.

When fully integrated, Golden Shield will be able to track almost every significant movement in their citizens’ lives. For example, biometric ID cards – compulsory for Shenzhen’s millions of migrant workers – are being introduced to store credit histories and education and medical records. Phone calls will be monitored through voice recognition and movement tracked through biometric ID cards. In sum, a massive, searchable database of names, photos, work histories and biometric data.

Naomi Klein has described Shenzhen at night as “glowing like a pimped-up Hummer”, while others have recognised it as a dazzling symbol of China’s rise, replete with 40-storey condominiums, penthouses and a new stock exchange designed by Rem Koolhaas.

That Shenzhen has become an economic miracle there is no doubt. It is an industrial powerhouse that makes everything from iPods to automobiles, but also a creative hub for south China’s leading-edge creative industries. It’s also a consumer cocoon, where western brands are brandished by its youthful elites and western lifestyles are copied conspicuously.

But the city is also a potential powder keg where demands for democracy are likely to break out at any time. Golden Shield seeks to “protect” its citizens not only from crime – which has fallen dramatically since the cameras were installed – but also from dissent. Indeed one Shenzhen company, China Security and Surveillance Technology, has already developed software to alert police when a “suspicious” number of people congregate. To Walton and others, including Klein, Shenzhen is becoming a city of nightmares, torn from the pages of Orwell’s 1984 and Zamyatin’s We: a prototype city-as-panopticon emerging out of the Pearl River delta.

What’s more, the technology behind Golden Shield could soon be extended across China and beyond. Systems that track our movements through national ID cards with RFID computer chips containing biometric information are being ordered around the world, as are systems that upload our images to police databases and link them to records of personal data. The US already has plans to build “Operation Noble Shield”, while citywide projects similar to those in Shenzhen are being introduced in New York, Chicago and Washington DC.

London currently has the densest concentration of cameras in the world, and the UK the largest biometric database on its citizens. And face recognition technology (FRT) could arrive in our cities this year. Most FRT systems note the relative position, size and shape of the eyes, nose, cheekbones and jaw and store them in a database as an algorithm. Prototypes have existed since the late 1980s, but only recently have they become reliable enough to be deployed on a large scale. In December St Neots Community College in Cambridgeshire began scanning kids’ faces to record the timekeeping of its tardier pupils. In Newham, East London, police are piloting FRT in an attempt to cut crime.

The Association of Chief Police Officers, meanwhile, is in consultation with the Home Office about the potential to link FRT with an existing surveillance network that reads and tracks car number plates. Moreover, Peter Neyroud, head of the National Policing Improvement Agency, has raised the potential of FRT being used in conjunction with behavioral matching software to spot potential suspects behaving suspiciously. The world of total surveillance depicted in the film Minority Report seems only a few clicks along the technological timeline.

“The Chinese mindset is way worse than ours,” explains Duncan Campbell, an investigative journalist who specialises in security issues. “But the toxic combination of lack of respect for basic rights and a control culture are here already … It’s not the specific technologies, we have all of those, it’s what can be done in the cultural and political context.” And there’s the rub. Alone, these various technologies are sinister enough. But it’s when they become integrated into a single, searchable database that they become frightening. Sir Kenneth McDonald, the former director of public prosecutions, describes the UK’s ever-growing array of spy tools as having the potential to present security services with a “complete read out of every citizen’s life in the most intimate and demeaning detail”. In February this year, the House of Lords and former MI5 director Stella Rimington separately warned of the grave threat CCTV and ID cards pose to our liberties.

Where does this all stop? Nobody really knows. But Shenzhen is just the vanguard of a global trend. One day you might wake up to find that everything you buy, every person you meet, and every move you make has been meticulously logged. They’ll be watching you.