words Charles Holland

The domestic history of West Indian immigrants is given a dusting by Charles Holland.

What do a soft-porn painting of a woman called Tina, the records of country crooner Jim Reeves and a decorative glass fish have in common? The answer lies in this book looking at the homes of West Indian immigrants to the UK.

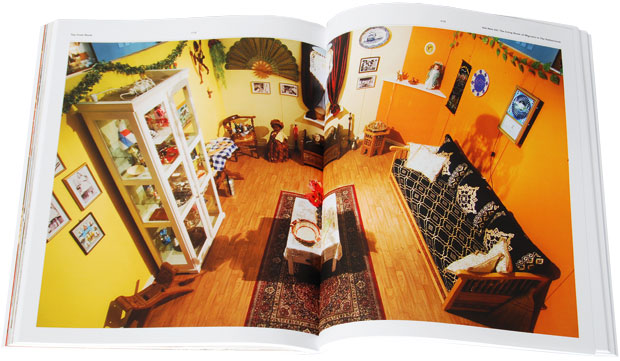

The Front Room has grown out of series of exhibitions and installations by the writer Michael McMillan. It features contributions from artists, writers and academics, most of whom are second-generation West Indians. Their stories reveal an astonishing consistency in how their parents’ houses were laid out. Almost all seemed to feature the same objects: exotically patterned carpets, thick velour curtains, decorative glassware and drinks trolleys featuring the ubiquitous plastic pineapple ice box.

The front room itself was a place of rich symbolic importance. New arrivals to the UK in the 1950s and 60s were often unwelcome in traditional social spaces such as pubs and clubs. The front room became a replacement, a kind of quasi-public space where all sorts of activities – ceremonial, formal and furtive – took place. It was kept “for best”, with plastic covers on the sofas and meticulously dusted ornaments. In some ways it was a direct descendant of the Victorian parlour, a space for formal display and the ceremonies of everyday life.

As well as mimicking the formalities of English domestic architecture, the front room imported some specifically West Indian elements. The stereo in particular was an object of hallowed status, connected to both church music and the public sound systems of Jamaica. It was thus ambiguous, reinforcing stereotypes of pious religious observance and late-night partying.

The importance of the objects collected here was a revelation to me. They are familiar enough today from junk shops and antiques markets, the kinds of things that are handy signifiers of 70s (bad) taste. Despite being a cause of amused embarrassment to the book’s contributors, they also have an un-ironic significance as both an expression of individual aspiration and collective belonging.

It’s good to see them lovingly recorded in all their proud glory. As well as telling their own story, they are a salutary reminder of the temporality of interior design styles and the touching belief of every generation in its own taste.

There is a slight sense though of the subject matter being stretched to fit this book. This isn’t for want of interest but more because the front room is part of a wider story, hinted by the book’s subtitle – Migrant Aesthetics in the Home. For architects, the history of houses is usually a linear sequence of formal or technological developments unconnected to questions of identity or ethnicity. There is another, alternative, history which is about the occupation and adaptation of homes and the different people that live in them. This book is an important part of that story.

The Front Room, by Michael McMillan, Black Dog, £19.95