words Daniel Miller

Mark Kingwell’s new book looks at the ways consciousness, the urban environment and ideas of the public sphere connect to make us what we are. Daniel Miller is intrigued.

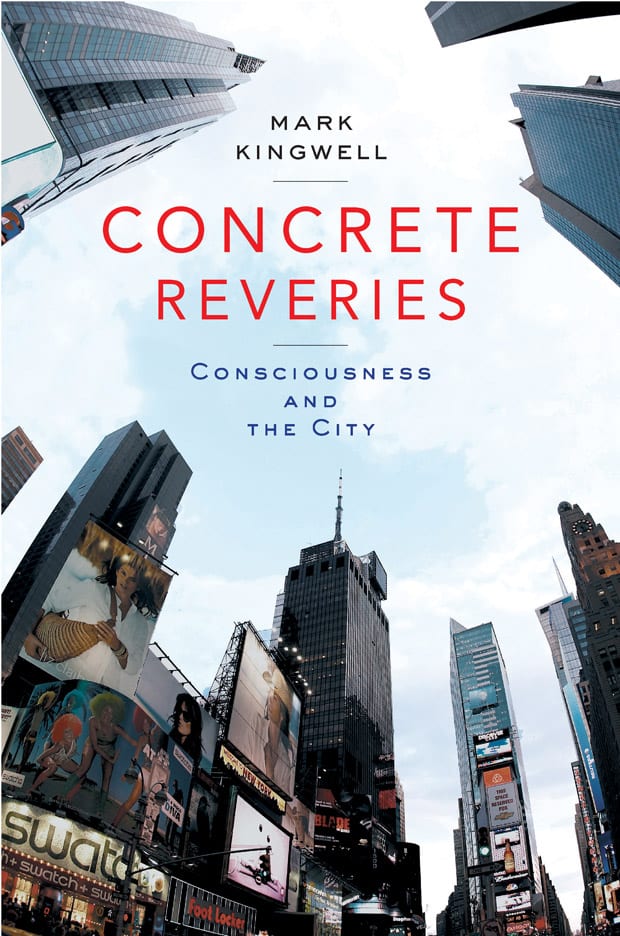

Books that blend architecture with philosophical inquiry generally fall into two camps. On the one hand, there are the murky and dense professorial torture manuals. On the other, there are the crystalline prose-poems of pellucid clarity. Mark Kingwell’s elegiac and graceful new work, Concrete Reveries, belongs to this latter category.

A professor of philosophy at the University of Toronto, and a contributing editor for the Canadian magazine Harper’s, the multifaceted Kingwell is the author of more than 10 books on topics ranging from justice, to fishing, to cocktails, to happiness. In Concrete Reveries he trains his attention on the ways in which human consciousness, the urban environment and ideas of the public sphere all intertwine and imply each other.

From the Stoic philosophers of ancient Greek (so-called because they used to meet on the steps of the “Stoa Poilkile” or “painted porch” of the Athens agora) to the coffee houses that were midwife to the birth of modernity, to the play-acting waiters who waltzed through the pages of Sartre’s philosophy, abstract thinking has always closely resembled the spaces which have nurtured and raised it. According to Kingwell, this is not accidental. “[E]pistemology and philosophy of mind,” he writes, “are linked to the real grids and spaces that we conscious entities occupy, the streets and places of actual cities. Epistemology is architecture, and architecture epistemology, because both concern our experience of the world as space.”

“And because architecture in turn concerns public spaces,” he adds, “we find ourselves in the realm of politics – which really we have never left.”

Kingwell contends that architecture should recognise its deeper commitment to responsible, engaged design. The essential urban problem, he argues, is to institute places, open and transparent sites that spur plural encounters. The model here is New York, a city Kingwell salutes as the capital of the 20th century. “Suppose you were lost in the city,” he says to his readers at one point, “without money or means of communication, and had to meet the one person who could help you. With no way of contacting this person … how would you do it?” For Kingwell, the “joyful and inevitable” logic of the geometrical Manhattan street plan means that this question has a right answer: “You’d go to Grand Central Terminal, at noon, and wait by the famous clock-capped information kiosk in the middle of the Grand concourse … Your party will be there too, because … within the logic established by the city, the many superimposed grids of urban sense-making, this is what counts as the correct answer. It is conventional, not metaphysical; but it is not contingent because it could not be otherwise.”

Kingwell hymns the savvy romance of New York coincidence, and the rugged democracy of the Manhattan grid, but believes that this model is now passing away. “At the asymptotic edge of design freedom,” Kingwell writes of Shanghai, “lies a sparkling, overgrown, hyperscaled city of bright nightmares, sometimes beautiful, often strange, always oppressive. Shanghai is modern urbanism on a speed high, rambling and incoherent, with a lump of shopaholic emptiness at its centre. Nowhere else on earth is the promise of architectural emancipation, that dream of modernism, more vividly broken.”

Whereas New York is “layered, fluid, always shifting between sovereign individuals, each dependent on all the others for their sovereignty,” the Chinese by contrast “know what we don’t, that Western individualism is a myth of significance in a world in which you’re really nobody and nothing”.

It’s a melancholic yet lucid insight that captures the rich, moody tone of the book as a whole.

Concrete Reveries, by Mark Kingwell, Viking Adult, $24.95

us.penguingroup.com