|

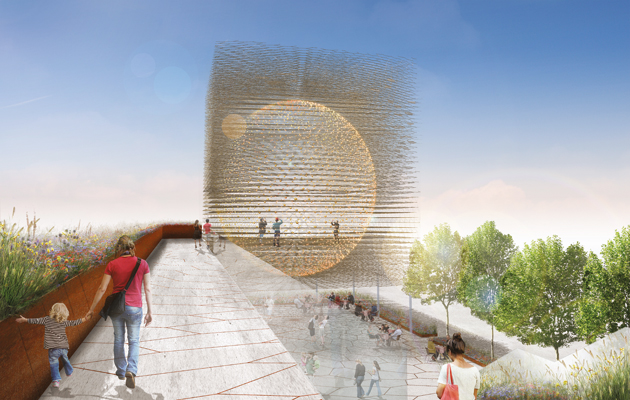

Wolfgang Buttress’s “hive” will incorporate thousands of LEDs |

||

|

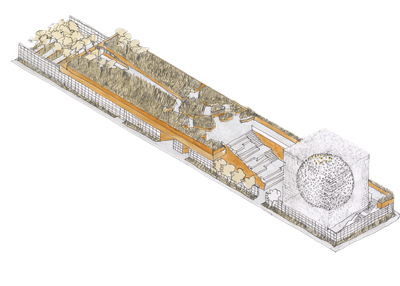

Architects have long been drawn to the honeybee colony as a symbol of an ideal, industrious society. Now for the British pavilion at next year’s Milan World Expo, Wolfgang Buttress is building a “pulsating virtual hive” out of honeycombed steel and LEDs In 1973 the Austrian zoologist Karl von Frisch was awarded the Nobel Prize for his research into bees. He tracked their movement to discover that, through their “circle” and “waggle” dances, they were communicating the sources of different kinds of food. Recent research at Nottingham Trent University’s School of Science and Technology has elaborated on von Frisch’s research using computer technology. Professor Martin Bencsik employs accelerometers to detect and translate the vibrations given off when bees communicate with each other in their hives. Every spring bees swarm, half of the colony leaving with the queen to find a new home, or more often to die. Bencsik can predict when the bees are planning to do this up to two weeks in advance, enabling beekeepers to catch and rehouse the bees, thereby both doubling the size of their apiary and saving the bees from harm. When researching the plight of the bumblebee, which is in well-publicised decline, the Nottingham-based sculptor Wolfgang Buttress was excited to stumble across Bencsik’s research. Their collaboration resulted in BE, the winning proposal for the British pavilion at next year’s Milan World Expo, which will address the theme of feeding the planet. Buttress saw off competition from designers and architects including Barber Osgerby, Amanda Levete, David Kohn, Asif Khan and Paul Cocksedge. (Thomas Heatherwick’s porcupine-like Seed Pavilion won the gold medal at the previous 2010 World Expo in Shanghai, making it a hard act to follow.) “Every third mouthful we eat is pollinated by a bee,” Buttress tells me when we meet in London to discuss his scheme, “So it’s really important to address this decline.” Using the full length of the narrow 100m x 20m site, Buttress wants to create a “visceral experience”, taking visitors on a journey through “a slice of the UK countryside transported over to Milan”. They will enter through an orchard and ascend a narrow stair that cuts through a wall of earth in which they will be able to see roots and worms. They will emerge from the ground into a field of wild flowers, chosen by landscape architect Nigel Dunnett, the man behind the planting scheme of the Olympic park. Buttress wants visitors to feel “in nature, not on it”, and the field will loom above them as they walk down a trench lined with rusty, earth-coloured Corten steel. Like a moth to the flame, they will be drawn to what Buttress describes as “a pulsating virtual hive that will highlight the plight of the honeybee”. This floating, spherical orb at the far end of the site will glow and buzz in a 12m cube of latticed, honeycombed steel. Tristan Simmons, who has assisted Antony Gormley and Anish Kapoor in realising their sculptures, is helping to make the structure as delicate and light as can be. Where the void meets the latticework, there will be thousands of LEDs, which will be digitally connected to a real hive equipped with Bencsik’s accelerometers to give an impression of its energy. However, no bees will be brought specially to the site, Buttress explains: “Forty to sixty thousand bees in the heat of the Milanese summer … everyone wandering about eating ice creams – there would probably be quite a few accidents.” He expects at least a quarter of the Expo’s predicted 20 million visitors to pass through his pavilion.

Buttress’s design includes an orchard and a field of wild flowers The beehive was an ancient masonic symbol, historically associated with architecture, and colonies of honeybees have long been thought of as metaphors for the ideal, industrious society. Their architectural instincts – which result in mathematically perfect, hexagonally partitioned honeycombs – have often been emulated by their human counterparts. In his intriguing book, The Beehive Metaphor: From Gaudí to Le Corbusier (2000), Juan Antonio Ramírez looks at the influence that apian metaphors and the “natural architecture” of bees have had on modern design. The apian model, he argues, was especially important to the genesis of modernism, which, in its attempts to reorganise society for a new communitarian era, projected all sorts of virtues on to bees and their hives. For example, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Honeycomb House – his first non-rectangular design – was made with a hexagonal structure, while his unbuilt Steel Cathedral was intended as a gigantic “mystical beehive”. Gaudí was fascinated by the hanging forms of honeycombs, which he inverted for his trademark parabolic arches, and the great hall of the Palau Güell, with its hexagonal tiles, resembles a huge hive. According to Ramírez, Mies van der Rohe’s revolutionary 1921 glass skyscraper, named the Honeycomb, was inspired by observation hives, which were glass-fronted so that the moral lessons of bees could be carefully contemplated. Le Corbusier’s personal copy of von Frisch’s The Dancing Bees (1953) was heavily annotated, and both his hexagonally planned ideal city and his 1922 residential skyscraper, which he called the Honeycomb Apartments, were influenced by apian metaphors, the latter’s cellular structure echoing the raised form of a beekeeper’s portable hive. In renders, the British pavilion’s glowing dome looks like Buckminster Fuller’s 1967 Montreal Biosphere in flames. Fuller was also inspired in his geodesic designs by the “mathematical orderliness” exhibited by bees. Buttress, who has created spheres and domes in his public artworks, admits that Fuller has been a massive influence, not only in terms of the physics behind his structures but because of his concern with addressing the planet’s ecological plight. “There are important parallels between a beehive and human societies,” Buttress says, leaning on a well-worn metaphor. “They’re purely democratic and live as a single organism – every bee exists for the well-being of the colony, so I think we’ve got a lot to learn from them. In a way by learning what’s going wrong with our hives, we might be able to learn a few lessons about what’s going wrong not only with our eco-system, but with our society. They seem to be intrinsically linked.” |

Words Christopher Turner

Images: Wolfgang Buttress |

|

|

||

|

A honeycombed steel cube will enclose a spherical void |

||