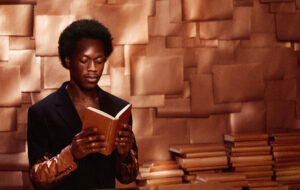

The British poet LionHeart, who collaborates with architecture practices, explains why emotion-centred design is so important

Words by LionHeart

For those who aren’t too familiar with the term, ‘emotional inhabitance’ is the result of empathic architecture, facilitating an emotional resonance between spaces and people.

Over the last three years, I have focused my research on emotion-centred design within architecture, in attempts to prioritise it more. That being said, after coining the phrase emotional inhabitance, there weren’t many architecture practices who initially saw the value in the research – or perhaps the poetic approach.

However, after establishing residencies with firms such as Grimshaw, PLP Architecture, Squire & Partners, Belsize Architects and MS-DA that were open to the idea, it soon became apparent the approach did have value. Beyond design, it also highlighted the importance of staff wellbeing within the industry’s culture.

Part of my work has been to challenge the thinking of those making decisions about the spaces we live and work in, by asking questions they rarely, if ever, hear. Questions such as: ‘You’ve got 10 minutes, can you design a section of a building that would mitigate someone’s mental health issues?’

Or my personal favourite: ‘Can you describe the person you love as a building or interior space?’ It didn’t occur to me that these questions would stretch an architect’s capacity to problem-solve. Nor did I become aware, until later, that there seemed to be normalised boundaries and problems which many found themselves up against – such as a work culture which rarely encouraged designers to challenge creative protocol or pay attention to personal needs.

My work uses poetry not only to present and conceptualise information, but to confront the status quo and challenge what tools should be harnessed when approaching architectural problems. Through one-to-one sessions with architects, there were revelations regarding emotional and psychological relationships with architecture – particularly those concerning mental health.

the room becomes a wedding ring

or it becomes a coffin, where my body

realises how living rooms too, can bury us

should we sweep our feelings under the rug.*

Some buildings have become urns

for how we once thought and felt.*

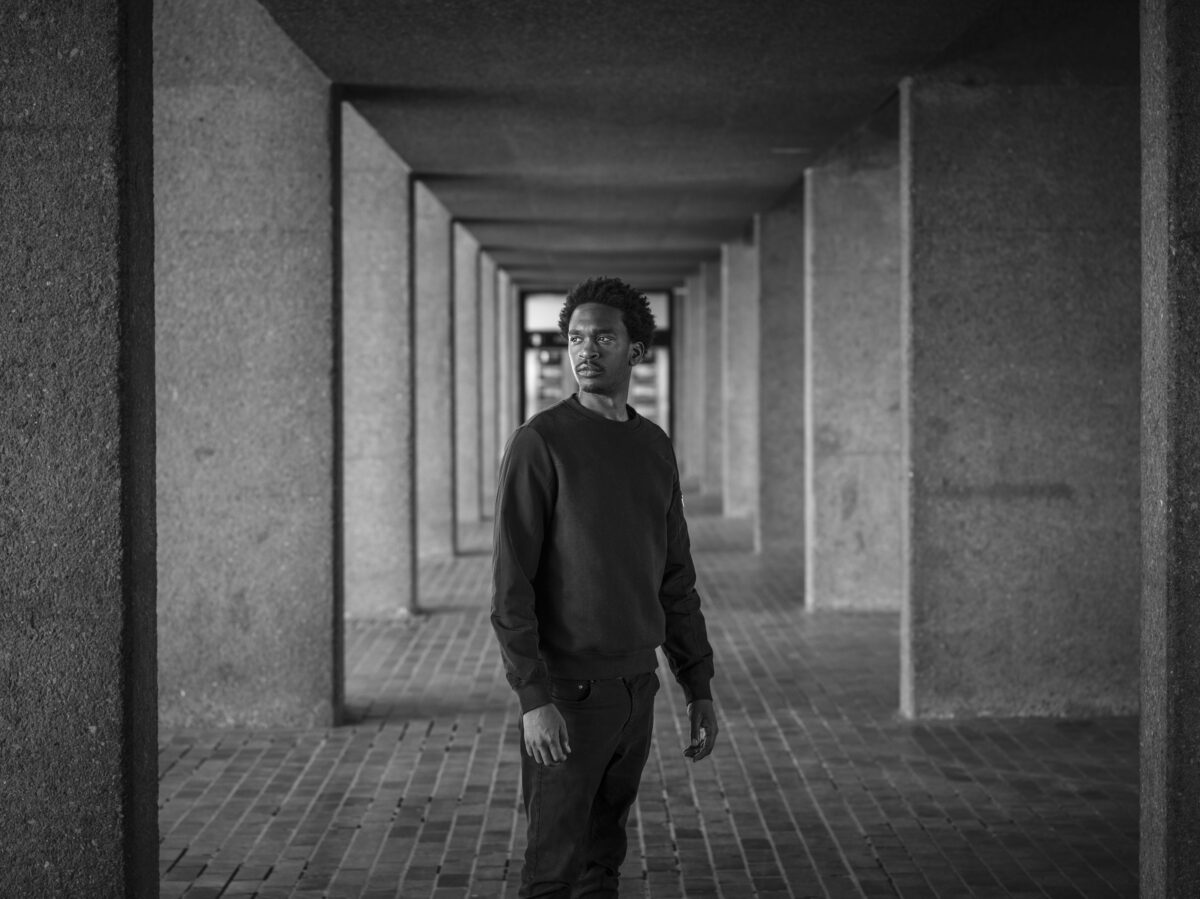

My own battles with anxiety and depression were ameliorated through spending time in brutalist architecture, such as the Barbican Centre and Southbank Centre, coupled with writing poetry. It made me aware of the subtle yet immersive power architecture can wield, to take you outside of yourself. The purpose of poetry here is both disarming and comforting.

Every experience

is an interrogation

with the wound of upbringing,

when we design like our mothers,

even protectiveness can harm

what it intends to protect.*

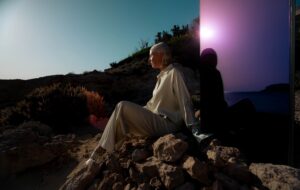

Architecture emotes. As much as poetry does, and it acquires a plot of our mental real estate in many ways. Specific architectural atmospheres, such as Peter Zumthor’s thermal baths in Vals, Switzerland, or the ancient Pantheon in Rome, have become familiar placeholders for healing and transformative buildings. And it’s no surprise that when inquiring into why, the answer tends to highlight the poetic nature of the spaces.

Which is definitely subjective. However, during my research there have been interesting correlations drawn between buildings which resonate with people, and most tend to be churches or places that exude an otherworldly quality of awe (the Pantheon was a key reoccurrence).

Understandably, my research was never intended to convince others that there is a universal bible of how to use space as a language to control how we feel. Rather, it was to bring feelings to the forefront of our minds more, to connect the dots of a road less travelled, and stretch our capacity, to stretch an architect’s sense of possibility, to add more beneficial design tools through poetry, to enrich our experiences and to nourish our mental health rather than detract from it.

to feel our way

through this maze of self love,

until our designs are cantilevers

of our courageousness

and not a third of our fragility.*

Architects need to consider the notion of emotional inhabitance in order to design spaces that support our mental health, because architecture can do as much for mental health as it can do against it.

LionHeart is a poet, author and radio presenter. Portrait photography by Thomas Farnetti / Wellcome Collection