From timber cohousing to privatised public space, here are 12 highlights of what’s on show this year, responding to the theme: How will we live together?

The Central Pavilion in the Giardini. Photo: Francesco Galli courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

The Central Pavilion in the Giardini. Photo: Francesco Galli courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Words by Francesca Perry

Apart from a select few (you know who you are), most of us were not able to be in Venice this year for the opening of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition (delayed from 2020). So I have done the legwork to scout out what’s on show and some of the highlights. But first, an overview.

This edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale is curated by Hashim Sarkis, Lebanese architect and dean of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, whose questioning theme – How will we live together? – invited architects to imagine spaces in which we can generously live together: as human beings, as new households, as emerging communities, across political borders, and as a planet.

As ever, the biennale comprises national participations – across dedicated pavilions and other installations – as well as an international exhibition. This year, there are 61 national participants – including debut presences from Grenada, Iraq, and Uzbekistan – and 112 participants from 46 countries in the exhibition.

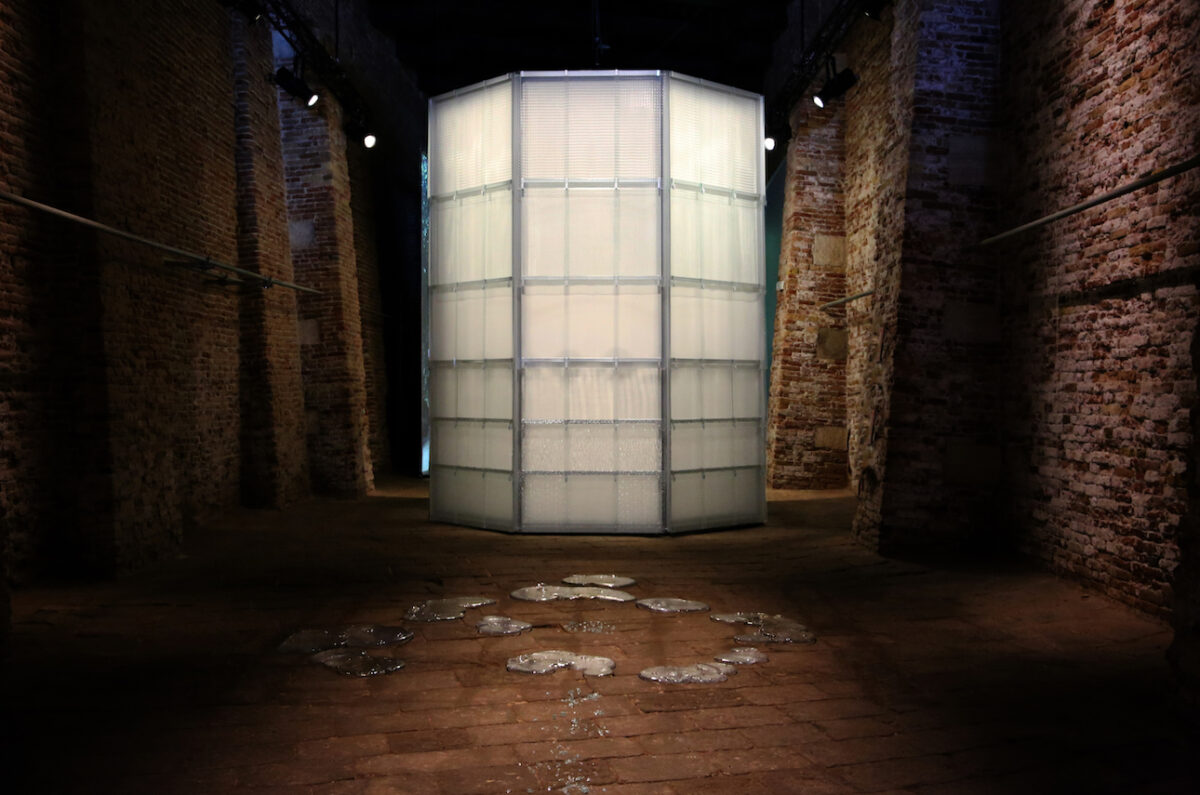

The Arsenale. Photo: Andrea Avezzù courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

The Arsenale. Photo: Andrea Avezzù courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

The exhibition, hosted at the Arsenale and the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, is organised into five sections responding to the main theme; some of the international practices and organisations exhibiting include atelier masōmī, OMA, Decolonizing Architecture Art Research, Elemental, Farshid Moussavi Architecture, Lina Ghotmeh and Superflux. Studio Other Spaces – co-directed by Olafur Eliasson and Sebastian Behmann – has collaborated with six designers to create Future Assembly, an ‘exhibition within an exhibition’ which reflects on the UN-inspired question: What could a multilateral assembly of the future look like?

An additional part of the exhibition – How will we play together? – takes place away from the Venetian islands over on the mainland, creating a children’s play-focused project at the 19th-century fortress Forte Marghera. There are also 17 collateral ‘events’ across the city.

Here are ICON’s 12 highlights of what’s on show. If you are able to visit, it’s open 22 May to 21 November 2021.

Lebanese Pavilion

Photo: Alain Fleischer

Photo: Alain Fleischer

Architect Hala Wardé presents A Roof for Silence, in collaboration with artist and poet Etel Adnan, film director Alain Fleischer and the Soundwalk Collective. Through an immersive and sensory installation blending multiple art forms, Wardé considers coexistence through looking at spaces of silence. Inspired by a group of ancient olive trees in Lebanon, the exhibition uses works of architecture, painting, music, poetry, video and photography to reflect on the olive tree as form, symbol and place.

Although conceived before 4 August 2020, the project also responds to the devastating Beirut port blast. The pavilion has offered its platform to the Beirut Heritage Initiative, a collective created to restore the built and cultural heritage of the city, to organise initiatives and mobilisation campaigns during the biennale. One of the exhibition’s works, Metamorphosis, also harnesses glass broken by the blast, collected in Beirut and scattered or melted by glass blower Jeremy Maxwell Wintrebert to materialise the impact of the explosion in the city.

Uzbekistan Pavilion

Photo: Gerda Studio

Photo: Gerda Studio

For a pavilion representing Uzbekistan, surprisingly few Uzbek practitioners seem to have been involved in creating it. Curated by Swiss architects Emanuel Christ and Christoph Gantenbein (‘We had more questions than answers when we started the project,’ says Christ at the opening), the pavilion features work from Spanish filmmaker Carlos Casas, Dutch photographer Bas Princen, and CCA Lab, the research laboratory of the Center for Contemporary Art in Tashkent.

Titled Mahalla: Urban Rural Living, the exhibition explores the traditional ‘mahalla’ – an Arabic word describing a traditional neighbourhood managed at the community level – as an alternative urban form of living together. Though Uzbekistan has over 9,000 mahallas, they are slowly being replaced by new types of housing due to economic pressures, outdated infrastructure and changing lifestyles. The exhibition comprises a 1:1 outline model of a typical mahalla courtyard house, as well as a soundscape of mahalla sounds by Casas, photographs of mahalla houses by Princen, and a tapchan (a type of outdoor furniture) designed by CCA Lab in collaboration with Uzbek artist Saodat Ismailova.

British Pavilion

Photo: Cristiano Corte courtesy of British Council

Photo: Cristiano Corte courtesy of British Council

As a British magazine it feels inevitable we’d cover the British Pavilion, but honestly I am so delighted by this contribution from curators Madeleine Kessler and Manijeh Verghese from Unscene Architecture. As an exhibition, The Garden of Privatised Delights tackles the privatisation of public space in the UK today through a series of interactive installations that consider the role that design and architecture can take in supporting more inclusive places.

Working with five teams of designers and researchers – The Decorators, Built Works, Studio Polpo, Public Works and vPPR – Verghese and Kessler propose new ideas for ownership of, and access to, public space. The rooms of the pavilion are transformed into seven privatised public spaces – from the pub to the youth centre, the garden square to the high street – reimagined as inclusive, immersive experiences. The exhibition’s fantastical scenography, meanwhile, takes cues from Hieronymus Bosch’s surreal triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights, a driving inspiration for the project.

Philippine Pavilion

Photo: Andrea D’Altoe

Photo: Andrea D’Altoe

A beautiful wooden structure occupies the venue for the Philippine Pavilion this year, but there is so much more to the project than a pretty building. Titled Structures of Mutual Support, the Philippine contribution focuses on mutual support (or ‘bayanihan’ in Filipino) as an approach to both architecture and community building. Led by architects Sudarshan V Khadka and Alexander Eriksson Furunes, the project included a long-term collaboration with 32 community members of the Gawad Kalinga Enchanted Farm, located north of Manila.

The process involved asking participants what kind of space they wanted to create and have in the community, before collaboratively planning, designing and building it. Together, and through an experience in which skills were shared and relationships built, the group constructed a library space using local wood. The space was then dismantled, shipped to Venice and reconstructed, where it will remain for the biennale before returning to take its place in the Gawad Kalinga community. ‘We were all in this together,’ says one of the participants in a film launching the pavilion.

Mexican Pavilion

Titled Displacements, this year’s Mexican Pavilion – curated by Isadora Hastings, Natalia de La Rosa, Mauricio Rocha and Elena Tudela – reflects on social and natural displacements, including inequality, environmental degradation, disaster and violence. The sensory pavilion seeks to promote architects’ ability to recognise and analyse the different forces that drive displacements, in order to help build more equitable, autonomous, and desirable places. The aim is to explore ways in which to design and build spaces of belonging, reconciliation, storytelling, exchange, recovery, assimilation, forgiveness, and resistance resulting from displacement.

Applied Arts Pavilion Special Project

Photo: Andrea Avezzù

Photo: Andrea Avezzù

Collaborating with author and architect Shahed Saleem, the V&A presents an exhibition titled Three British Mosques, exploring contemporary multiculturalism through three adapted mosque spaces in London. Reflecting on the self-built and often undocumented world of adapted mosques, the three case studies examine the Brick Lane mosque (a former Protestant chapel then synagogue), Old Kent Road mosque (housed in a former pub), and Harrow Central mosque (a purpose-built space sitting next to the converted terraced house it used to occupy). The stories of these places are explored through architectural reconstructions, filmed interviews and photographs.

Dutch Pavilion

The Multiplicity of Other. Photo: Cristiano Corte

The Multiplicity of Other. Photo: Cristiano Corte

The Dutch Pavilion, presented by the Het Nieuwe Instituut and curated by Francien van Westrenen, hosts the exhibition Who is We? with contributions from architect Afaina de Jong and artist Debra Solomon. De Jong’s colourful installation, The Space of Other (created in collaboration with InnaVisions), challenges the ‘we’ in ‘How do we live together?’, focusing on othered perspectives. ‘What would a space look like that takes into account different concepts and is based on a different set of values?’ De Jong asks at the virtual pavilion opening. Solomon’s work, Multispecies Urbanism, advocates for just urban development driven by inter-species relations of care and climate crisis mitigation. ‘We are a relational species,’ van Westrenen says. ‘We have to look beyond ourselves and see ourselves as part of a bigger whole.’

The Majlis

Photo: Simone Padovani/Awakening/Getty Images

Photo: Simone Padovani/Awakening/Getty Images

At the San Giorgio Monastery on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, a new bamboo structure called Majlis has been installed, alongside a permanent productive garden. Presented by Caravane Earth Foundation – a foundation championing natural and ethical art, craft, architecture and agriculture – the Majlis is designed by Colombia-based architects Simón Vélez and Stefana Simic. It is wrapped in woollen textiles handwoven in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco by a women’s collective from Ain Leuh, and the Boujad Tribe. ‘The purpose is to illustrate the importance of intercultural dialogue and traditional natural crafts,’ says Caravane Earth director Fahad Al-Attiyah.

Deriving from an Arabic word meaning ‘council’ or ‘gathering place’, the Majlis is conceived as a space for people to come together and will be programmed with a range of events throughout the biennale. ‘We are not making this for tourism or fun, but to make a cultural place for learning,’ says Vélez in a launch film. The structure is located in a productive garden newly designed by landscape architect Todd Longstaffe-Gowan; while the Majlis structure will travel the world after its stint at the biennale, the garden will stay in Venice permanently.

Chilean Pavilion

Photo: Gerda Studio

Photo: Gerda Studio

Testimonial Spaces, the installation for the Pavilion of Chile, comprises a serious of 500 testimonies from residents of the José María Caro settlement transformed into 500 paintings, housed within a bright blue-painted wooden structure. The settlement is located south of Chile’s capital Santiago and forms part of a planned process of social integration led by the government in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Its aim was to bring different social classes together within the same territory, including settlements for middle-class workers, members of the armed forces and government employees. Curated by architects Emilio Marín and Rodrigo Sepúlveda, Testimonial Spaces focuses on capturing memories, hopes, and the spatial tactics of life in the settlement.

Nordic Pavilion

Photo: Chiara Masiero Sgrinzatto and Luca Nicolò Vascon

Photo: Chiara Masiero Sgrinzatto and Luca Nicolò Vascon

Timber housing is a real *thing* at this biennale – the Nordic, Finnish and US Pavilions all focus on it. All are interesting explorations, but a favourite is the Nordic Pavilion. Norwegian architecture firm Helen & Hard has transformed the (already striking) space into a full-scale section of its solid wood cohousing project Vindmøllebakken, in close collaboration with a group of residents. Titled What We Share, the exhibition presents a framework for designing and building communities based on participation and sharing, in response to an ‘urgent need’ in the housing sector to explore new models of communal living. The project challenged the Vindmøllebakken residents to develop an even more radical version of cohousing: which functions or social situations could they move out of their apartments and share with other residents?

Danish Pavilion

Photo: Hampus Berndtson

Photo: Hampus Berndtson

Titled Con-nect-ed-ness, the exhibition within the Danish Pavilion focuses on people’s connection with each other and with nature, in a sensory installation consisting of a giant cyclic system of water collected locally in Venice. Curator Marianne Krogh and architecture practice Lundgaard & Tranberg propose that a more connected approach of living together, in which resources are shared rather than divided, could work towards tackling the climate crisis among other urgent challenges.

Water in the pavilion is collected on site, and climatic fluctuations continuously shape the look and feel of the exhibition – for example, parts of the pavilion are flooded. While exploring the exhibition, visitors can become part of the cyclic system by drinking a cup of tea brewed with leaves from the lemon verbena trees planted in the pavilion – trees which also absorb water from the extensive cyclic system.

Korean Pavilion

Instead of an artistic gesture or a built form, this year’s Korean Pavilion is conceived as an educational and propositional space of discussion, exchange and learning. Titled Future School and curated by Hae-Won Shin, the project converts the pavilion into a space for thinkers and practitioners from around the world to assemble and tackle three critical subjects: diaspora, climate crisis, and innovation. Future School participants are invited to engage in acts of radical thinking through workshops, lectures, performances, and exhibitions. Parallel programming runs concurrently in Seoul for all 25 weeks, with regular live broadcasts between campuses and beyond.

Get a curated collection of architecture and design news like this in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter