|

The Venice Biennale Japan pavilion’s take on the theme of “Absorbing Modernity” focuses on a period in the 1970s when, with the country rushing into the free-market future, a group of architects turned instead to the vanishing past A treasure house of fragments and forgotten experiments – in this Wooden crates, scaffolding and orange construction fencing, physical relics, original models, blueprints, unpublished manuscripts, oil drums, and trestle tables conspire to give the exhibit the feel of a working site, implying that the historical excavation on display is currently in progress. This is a historian’s construction site, a place where the past is actively composed as a bricolage of fragments unearthed from dusty oblivion. And it is indeed a historian who is the curator of the show: Norihito Nakatani, an architectural historian at Waseda University in Tokyo is known for his interest in the vernacular buildings, unconscious landscapes, and historical figures excluded from mainstream historical narratives. Nakatani was commissioned by Kayoko Ota, a long-time associate of Rem Koolhaas, and the exhibition was designed by another Japanese OMA ex-staffer, Keigo Kobayashi, himself now returned to Japan to take up a position at Waseda University.

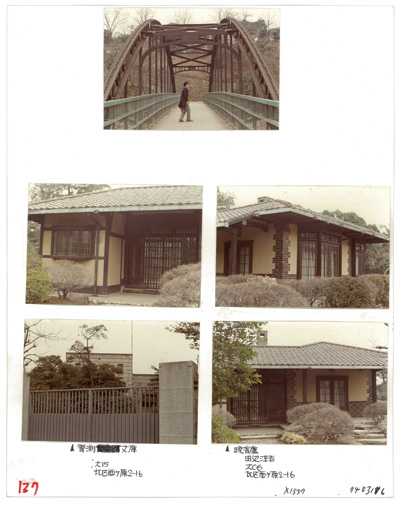

A villa in suburban Kita-ku ward in Tokyo, built in 1917 The show, titled In the Real World, takes Koolhaas’s prompt – to explore the national experience of absorbing modernity over the past century – at face value, but chooses to focus its exploration on the 1970s, a decade in which the promise of modernisation and the forces which it unleashed were increasingly questioned and rethought. Every culture has its own complex interaction with modernity, even those ostensibly at the centre of the whirlwind, as demonstrated by the French and British pavilions in their different ways. But the Japanese encounter with architectural modernism in the 20th century is particularly inflected by the fact that many principles advocated by modernist architects in the 1920s were already prefigured in the local tradition of timber architecture – including dimensional modularity, prefabrication, programmatic flexibility, spatial flow and interpenetration, truth to materials, a rejection of ornament, and a formal aesthetic favouring asymmetry and incompleteness. As the German Bauhaüsler Bruno Taut observed in his celebrated account of the 17th-century Katsura Palace of Kyoto in 1936, “Its principle is obsoletely modern, and of complete validity for contemporary architecture.” Architectural modernism, on this reading, could be as much an elaboration of Japan’s own traditions as an imported ideology from the West. It was Kenzo Tange who most completely realised this vision of a nationalistic Japanese modernism, elaborating his powerful synthesis of sculptural Corbusian béton brut with the native constructional clarity epitomised by the Ise shrine as Japan rebuilt itself anew after the devastation of the war. Tange was also midwife to the birth of the metabolists, whose audacious propositions for radical urban extensions built around flexible armatures of megastructures and capsules captured the imagination of the world in the early 1960s, and a little later that of the Japanese state. It is this moment in the story of Japanese modernism whose historical echo has been amplified recently through Project Japan, Koolhaas’s own homage to the metabolists, presented as a stirring tale of architectural ambition allied to state power and a lament for the loss of ideals of collective endeavour under the corrosions of the market. In the Real World takes up the story of Japan’s absorption of modernity where Project Japan leaves off, and picks up threads that it leaves out. The rapid urbanisation and state-led projects for industrial development that powered Japan’s growth in the 1960s imposed huge costs on the environment, an issue that became increasingly urgent as the decade progressed. The co-option architects in the service of questionable state goals that rode roughshod over local populations rankled many who sought a more critical distance from power. Arata Isozaki, responsible for the programming of the main space of the Osaka World Expo in 1970, likes to tell the tale of his nervous breakdown and hospitalisation on the day of its opening in terms of this tension between complicity and criticality in relation to modernisation, a tension felt acutely by the younger generation.

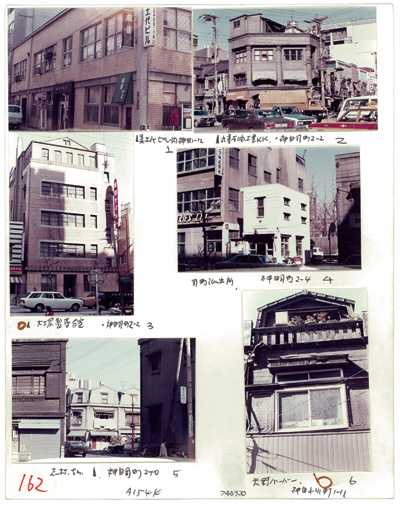

Sites in the Kanda district of central Tokyo After the oil crisis of 1973 brought the economy to a juddering halt, it was this generation – among them Toyo Ito, Hiroshi Hara, Osamu Ishiyama, and Terunobu Fujimori – suddenly liberated from the pressure to build, that embarked upon the wide-ranging questioning of modernism that has been excavated in the show. The diverse materials brought to light have been gathered under a number of headings, the most significant being “Retrieving the Neglected”, “Tracing an Unconscious Will”, “Involving Users in Design”, “Learning from the Vernacular” and “Making the Market an Ally”. The particular tenor of the era can be felt here in the switch in emphasis from the future to the past, the general to the particular, the collective to the individual, the elite to the common, and the state to the market. That the last development, perceived today by so many as a deplorable shift inimical to genuine creative flourishing, could be seen as an emancipatory movement by young architects of the day is fascinating to observe. It is genuinely surprising to learn of the shared experimentation with prefabricated housing designs and DIY materials that Ishiyama and Ito, assisted by a young Kazuyo Sejima and Itsuko Hasegawa, pursued in their early careers, all in the name of bringing architecture closer to the ordinary user. One interesting episode in this story was Ito’s House Commodification Study Group, active from 1981-83, which developed a demountable steel frame system for house construction inspired by Le Corbusier’s Dom-ino concept. While this only resulted in one completed project (the Umegaoka House of 1982), Ito recalls that it represented an increasing engagement with the turn to consumption in Japanese society. In an interview in the exhibition catalogue, Ito says: “Our undertaking was in a sense naive and quite pure. We were sensitive to the way in which society was becoming more consumption-oriented and gave serious thought to how we ought to respond to that change, without simply accommodating ourselves to it.” The most engaging section of the archive contains the materials documenting the cluster of activities focused on observing and reading the city. This occurred in a number of configurations – the Hyperart Thomasson Observation Center project pursued by the artist Genpei Akasegawa from 1972; the Architectural Detective Agency set up by Fujimori and building conservationist Takeyoshi Hori in 1974; and their later joining of forces as the Street Observation Academy established in 1986. These initiatives aimed to document, name, classify and publish the hidden, neglected, useless or even absent buildings and fragmentary artefacts found in the city as directly lived and experienced, not as described in urban planning or architectural history textbooks. Fujimori’s interest was initially in documenting the rapidly disappearing everyday structures from the prewar period, which had been ignored by mainstream histories as being untutored, vernacular products of popular culture and hence academically valueless. Akasegawa was concerned to recover the strange relics and ghostly traces of former spaces and lives, left over as fragmentary residues while the city rushed headlong into its modern future. He dubbed these useless artefacts “Thomassons”, after an American baseball player brought at great expense to Japan but who failed to ever score a point for his team – an emblem of poignant uselessness, cut off from original context and marooned in a foreign world. The first and most iconic Thomasson discovered was a stairway to nowhere, a so-called “pure stairway”, whose destination has long since ceased to exist. These urban surveys, focused largely on Tokyo at first and then later extending further afield, consisted of strolls plotted semi-systematically through the various districts of the metropolis, armed with camera and notebook, with findings from these hunts shared and discussed, often with great hilarity, in the evening. The members of these expeditions were rescuing the residues left behind by modernity and consumer society, giving life, in Fujimori’s words to “a dead world, which would never see the light of day”. “I wanted to treat that dead world,” he continued, “as if it were alive, or to put it another way, to try to create a different reality.” In method and intent, these expeditions shared resonances with the dérives of Guy Debord’s situationists in Paris and the psychogeographic wanderings of Iain Sinclair and confrères in London. However, the activities of the Street Observation Academy were simultaneously more systematic and less burdened with theoretical baggage than their European counterparts. Writing on this comparison in his recent book Tokyo Vernacular, the urban historian of Japan Jordan Sand observes that “the situationists saw themselves as the radical agents engaged in reinventing urban space; the observationists saw themselves as bringing to light an urbanism already latent”. When the contents of the Japanese Pavilion are seen in its international context, particularly against the neighbouring pavilions of Russia and South Korea, what is revealed with striking clarity is not the uniformity of modernity, but its tremendous multiplicity, both within and beyond national boundaries. Japan has always offered an alternative modernity to the outside gaze; here it offers an alternative modernity to itself, one which may offer hints to shaping its own alternative future. This article was first published in Icon’s August 2014 issue: Venice Biennale, under the headline “Architecture detectives”. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

Words Julian Worrall

Images: Terunobu Fujimori, Luke Hayes |

|

|