|

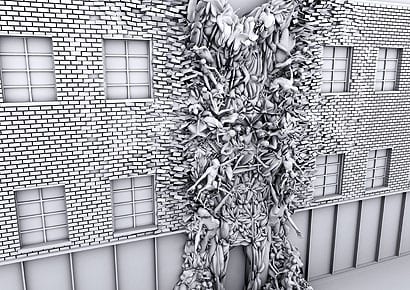

“We’re well on the way to having architects as hairdressers,” warns architect and writer Neil Spiller. He’s talking about style. Exactly a century after Adolf Loos’ seminal text Ornament and Crime, architects are using digital technology to generate elaborate decoration. But what are they trying to say with all their filigreed and tessellated patterns? Now that anything is possible, how do you choose what to do? And how do you know what’s radical anymore when radicals are “going baroque”? “Aesthetic discourse is the hot button issue for the next few years,” says Greg Lynn, one of the most prominent digital architects of the last decade. You don’t have to look very hard to see what he means. Take Foreign Office Architects’ John Lewis department store in Leicester, a glass box covered in floral swirls that wouldn’t be out of place in a William Morris pattern book, or Francis Soler’s Ministry of Culture in Paris, based on Hector Guimard’s art nouveau Metro stations. Caruso St John is building a contemporary art museum in Nottingham with lace patterns embossed into its concrete surface, making reference to extinct local industry. Perforated facades, a feature fast becoming ubiquitous on new buildings, are sometimes fractilinear and abstract and sometimes figurative. BIG’s Mountain housing in Copenhagen has a facade laser-cut to depict a mountain. This decorative tendency is even more apparent at London’s architecture degree shows. There are patterns everywhere, classical orders, hyper-baroque and, most strangely, caryatids, human bodies and organic structures. Oliver Domeisen teaches a design studio at the Architectural Association which looks back, of all things, to rococo, that most ornate and some might say vulgar of styles. For him, “abstraction is a retreat”; we have to reintroduce the notions of beauty and figuration to architecture in order to give it meaning again. Domeisen wants architecture that is “voluptuous and eloquent”, and he regularly uses words such as “beautiful” or “sensual” to describe it. Over at the Bartlett school of architecture, Neil Spiller’s students have been turning to theories of the baroque for inspiration. Spiller has been a strong promoter of digital architecture for nearly 20 years, and for him looking to the baroque is useful because “it deals with repressed psychosexuality, which is something architecture really doesn’t deal with very well”.

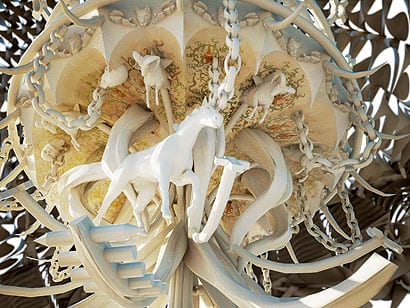

Barlett graduate Yousef Al-Mehdari’s Monesthetic Shrine This aestheticisation is driven by new technology. Design and fabrication tools are reaching a critical level of sophistication – at the design level, 3D scanners can create digital copies of objects of any scale and new “haptic” tools allow for sculpting in the digital environment, giving unprecedented spatial freedom and creativity. More importantly, fabrication technologies are advancing rapidly. Parts can be milled, cut, 3D printed and moulded with greater ease than ever, and components are increasingly manufactured directly from CAD models. However, with this freedom of creation comes responsibility: architects are “tooled up” as never before, but, as Domeisen says, “When everything is possible, the difficulty is choosing what to do.” These decorative tendencies seem to be a reaction to the smooth and abstract digital architecture that is designed using “parametric” scripting – basically computer programming in 3D. Its advocates claim that it optimises performance and efficiency, but Lynn disagrees. “You can only justify curvilinear shapes for so long with programmatic analysis,” he says. “Parametric software is just a tool, nothing more – scripting is basically accountancy,” says Domeisen. Spiller agrees, arguing that “parametric urbanism and design have no real idea of the way that cities work, it can’t really be anything more than a game”. But is ornament useful or decadent? Does it fulfil a need for narrative in architecture? In her books The Function of Ornament and the forthcoming Function of Form, Farshid Moussavi of FOA has attempted to develop a technical theory of ornament. Trying to escape the rigid opposition of form/function she argues for a theory of “affects”, basically meaning that how something looks can be examined in the same way as how well it keeps the rain out. This attitude leads to FOA explaining the patterns on the facade of its John Lewis building in terms of how they permit or block views and light. Similarly, Domeisen recently co-curated an exhibition titled “Re-Sampling Ornament” which also took a highly technological approach to the subject, focusing on ways in which ornament functions as well as decorates. Is this the only way ornament can be justified? “Architecture always validates itself in technical language”, says Charles Holland of FAT, which for the last 15 years has created an architecture full of ornament and historical reference. He’s suspicious of the rationalist justification for ornament, suggesting that architects are “rediscovering the enjoyment and pleasure of ornament and metal filigree” – it’s just that they can’t admit to it: “Both the rejection and the re-embracing of ornament seem to be rationalised in a technological way. We’re not interested in the jigsaw, we’re more interested in the picture.”

Royal College of Art project by Jordan Hodgson It’s not just about pattern, in many ways these new developments are a new form of figurative architecture. Are we not harking back to postmodernism? Lars Spuybroek, one of Europe’s most significant digital theorists, believes that “architects that use pattern as image are still postmodernists, they use pattern as independent from massing, as wallpaper”. If this is so, it’s ironic that the “digital avant-garde” of the 1990s was reacting to the tasteless overgrown pediments and pastiche that haunted architecture in the 1980s. Perhaps because of postmodernism’s links to corporations and conservative politics, many early digital architects sought to justify their work in terms of radical philosophy. This latest incarnation of the avant-garde has no such pretensions. Domeisen actually bursts out laughing when he hears the term “avant-garde”. There seems to be a general acceptance that “radical” architecture is a naive, outdated idea. Spuybroek agrees: “Architecture is following art more and more: no movements, no collectives, just atomic individuals.” So are architects becoming “hairdressers”, as Spiller suggests? “One could do worse than being compared to Vidal Sassoon in my opinion,” says Lynn. However, Spiller believes “radical” architects need to address desperate ecological issues and that “to be arguing over styles is to be missing the point really, there are bigger fish to fry.” Spuybroek pessimistically agrees: “I often feel that nowadays you either get expressive massing with smooth skins or expressive textures on dead boxes. I think smooth shapes are a mistake, they are sculptural … the feelings they evoke are of the sublime. Textured boxes are as bad, since their patterned skins are indifferent to the massing, and so become a thing of fashion.” This crisis of taste would have sounded familiar to the Victorians. In the 19th century moral arguments raged about which style of architecture was the “correct” one, and many buildings eclectically mixed elements from all manner of revived modes. Spiller, referring to contemporary bio-mimetic and “green” architecture, says “The Victorians had the battle of the styles, and this had a lot to do with God, but today we have a different set of criteria; you have the language of naturalism, giving us a certain digital art nouveau with nature as a moral replacement for god in some ways.” Spuybroek name-checks Owen Jones and gothic revivalists like Waterhouse, and confesses that he is “pretty obsessed with John Ruskin, and his views on variation and imperfection”. Although he thinks that “all that rococo stuff is basically classicism on acid”, he still believes that “the use of ornament is our only way out of this mediated, iconised world of images that we live in, and can bring aesthetics back into a much wider ecological realm.” The terms of the debate sound strangely conservative. Domeisen disagrees: “The real conservatives are architects who continue to make modern and minimalist architecture.” Yet when the best contemporary architects churn out 3D logos and when the radical edges of digital architecture are going historical, it is worth noting a precedent from history. It was during the rampant revivalism of the 19th century that the seeds of modern architecture were sown: namely, the revolution of iron and glass architecture. So perhaps while we quibble about the meaning of these digital aesthetics the new paradigm is quietly taking shape elsewhere.

Fouquet’s Barriere Hotel, Paris, by Edouard Francois

Adam Bryan Johnston’s Iconographic Object, from Oliver Domeisen’s unit at the Architectural Association |

Words Douglas Murphy |

|

|

||

|

Francis Soler’s Ministry of Culture, Paris |

||