All images courtesy of Studio Verter

All images courtesy of Studio Verter

As they prepare for their biggest commission so far at Biennale Interieur, Anna Winston asks what they will make of a bigger stage

‘We’re a little bit like a Bonnie and Clyde, but we don’t commit crimes,’ says Claudio Saccucci, of his personal and working relationship with his partner and fellow architect Roxane Van Hoof.

Working from a railway arch in Rotterdam, the duo behind Studio Verter are on the cusp of completing their first major project, the design of the scenography that will greet visitors to Biennale Interieur in Kortrijk, Belgium, which, as one of the world’s oldest and most respected design fairs, has launched the careers of many of the region’s biggest names.

It’s a big leap for such a young studio, with only a handful of small competitions and some impressive visualisations under its belt. The duo are part of a new generation that can help the design industry face up to some of its key challenges, according to Biennale Interieur’s organisers. With a combination of Italian, Dutch and Belgian influences, they promise an approach to architecture that is critical, thoughtful, experimental and detail-oriented, with interests in architecture that, above all, is sympathetic to its users.

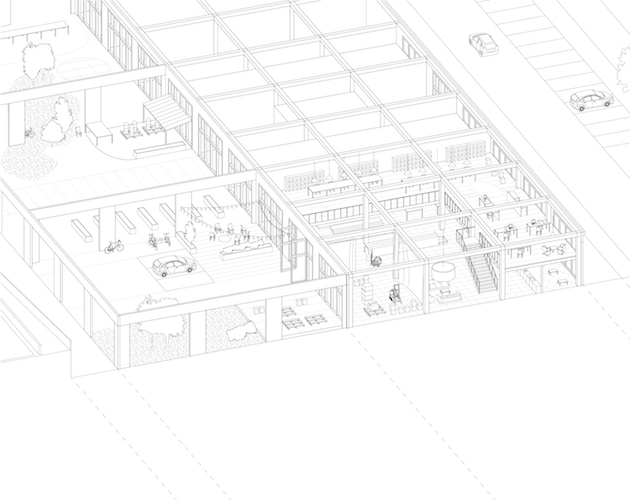

A plan for an Amsterdam social housing complex by Studio Verter

A plan for an Amsterdam social housing complex by Studio Verter

The mixture of influences is also reflected in their own dynamic. Van Hoof, who has wanted to be an architect since the age of six and still owns drawings of the houses she designed as a child, comes across as the more sensible of the pair, Saccucci the more passionate.

The Biennale’s creative co-ordinator Dieter Van Den Storm describes their work as ‘poetic’, an idea that is clearly supported by its visual language. Van Den Storm has worked with Saccucci before – the architect was part of a team that designed a bar for the Biennale’s awards programme in 2016, and was impressed enough to invite them to pitch for the biggest element of the following show, which opens on 18 October.

Van Den Storm describes the previous project as a vision of emerging beauty, despite its material focus on fungus. ‘There was nothing to see in the beginning except white cushions that were sprinkled and heated over the whole period. Slowly, mushrooms came out,’ he says. ‘At the end of the Biennale it was a big field, filled with mushrooms. It was a living installation.’

‘I hope this Biennale shows their potential to the outer world,’ he adds. ‘It’s a totally different scale they are working on. We’re talking about 40,000sq m. Their poetic approach will still be very tangible, which is hard to do on such a level, especially if it’s for the first time.’

The Biennale project centres on an imagined city square to be created by Studio Verter within the cavernous halls of the Kortrijk Xpo Centre, intended to introduce a social space and some much needed colour. A semi-translucent white facade, punctured with regular openings, will create an interior volume inside the centre, and a series of ‘landmarks’ will populate the floor, to resemble the statues and public art found in traditional piazzas. These are by a mix of young architects and sculptors, all from a wish list drawn up by Van Hoof and Saccucci, including a kaleidoscopic obelisk by British architect Adam Nathaniel Furman and a building block construction by Belgian artist Conrad Willems.

Unfazed by the duo’s lack of experience, the Biennale’s organisers have, essentially, let them get on with it, putting trust in them to deliver the show’s centrepiece.

Studio Verter Wine Valley Pavillon collage

Studio Verter Wine Valley Pavillon collage

Saccucci says the pair aimed to take a radically different approach to previous years’ scenographies, which have referenced a Parisian boulevard and Manhattan avenue. Rather than flattering the gigantic space, Verter were interested in juxtaposing something more human within the whole, reflecting a growing consumer interest in social responsibility and human wellness. ‘Design is moving very fast – but expos and these physical expressions of coming together have been very slow to adapt to these new trends. So in a sense our project was to materialise a square that was a representation of these new attitudes.’

For now, there are no big plans for the future beyond the Kortrijk commission. ‘We don’t have a game plan really. For now, it’s working,’ says Van Hoof. ‘It’s nice to be able to find your way in a project like this, where the contractor is already known – it’s like a practice run for a real building.’

Their debut commission reflects a journey that began at architecture’s other extreme, with an education amid professors who specialised in the experimental shape-making of late 20th century Dutch architecture at TU Delft. Van Hoof is originally from Amsterdam, while Saccucci grew up in Rome. The two met (and fell in love) while studying in Delft for an architecture MA. Saccucci’s path there was a little more convoluted – via an internship at Bjarke Ingels Group in Denmark – and, although Van Hoof is four years younger, they graduated a year-and-a-half apart – ‘I took a little bit longer to graduate because I wanted to do my things,’ says Saccucci.

His thesis professor at Delft was part of OMA, the architecture behemoth co-founded by Rem Koolhaas, and, like many other young architects in Rotterdam, he ended up working there while Van Hoof completed her studies. Today he describes OMA as ‘the hard way’ but a useful experience: ‘OMA is an interesting bubble. It doesn’t really reflect the state of architecture on an everyday level. But you can learn a lot of different things.’

In 2016, they moved to Gent in Belgium. While architecture in the Netherlands had been typified by a kind of bombastic experimentalism, Belgian architecture had followed a different route, particularly in the northern region of Flanders around cities like Gent and Antwerp, with a quieter aesthetic focused on detail. In Belgium, the duo saw a model that they wanted to be part of.

‘This Flemish renaissance had started a couple of years before. After the experience at OMA and the education at Delft, which is very driven towards bigness and big challenges, we were really not looking for that kind of experience,’ explains Saccucci. ‘The Flemish scene deals in a serious way with a variety of scales, where a scenography or a single house get the same amount of attention,’ adds Van Hoof.

It was while working for different firms in Gent that they also began to work together, experimenting with ideas that they couldn’t put into use at the office. They quickly found that the combination of their backgrounds and shared appreciation for particular projects and imagery was an asset.

‘I don’t think we look to particular figures for influence, we can be inspired by a project or an image, a photograph or a detail,’ says Van Hoof. ‘Our approach really depends on us working together as a team. With the projects we’ve been taking on so far we’ve been able to really zoom in on small details and consider each part. In a firm there are often established ways of doing things, while we are interested in figuring out our way of doing things.’

As they began to work more on their own projects and invited competition entries, Saccucci landed a teaching role in Rotterdam, and the duo relocated. The city is a hive of young, small firms – many started by TU Delft alumni and ex OMAers – and is also just an hour from Amsterdam and from Antwerp, where Van Hoof works part time for META Architectuurbureau. ‘When you’re around Rotterdam you will meet at least one architect on the metro, or in the supermarket – they’re everywhere,’ laughs Van Hoof.

Since moving, they’ve noticed a change in both the Dutch and Flemish architecture scenes. The young architects of The Netherlands are less interested in big, headline-grabbing projects and are becoming increasingly interested in keeping their work at a scale where they can have more control and do projects they believe in. At the same time, the dynamic between developers and the state is changing in Flanders, meaning that the number of developer-led, commercially driven projects is growing, demanding a different design approach. For now, their own ambitions are humble, says Van Hoof. ‘For now we really enjoy figuring out ways of working together on this smaller scale because we can control the process and give attention to the smaller details.’