|

|

||

|

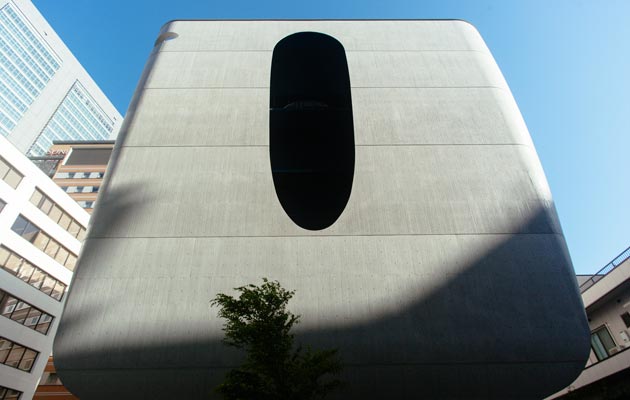

The hostess bars of Tokyo’s hedonistic Shinjuku district have an unlikely neighbour: Amorphe’s vast, futuristic Buddhist temple Hidden bars, neon billboards, hostess clubs, salarymen crowds, love hotels, shiny skyscrapers, packed crossings – and a temple. There are perhaps few more incongruous settings for a place of worship than Shinjuku, a district long regarded as the nocturnal underbelly of hedonistic Tokyo. Yet hidden among a bland row of office towers and hotels, just a three-minute stroll from the south exit of Shinjuku station – one of the busiest in the world – sits Rurikoin Byakurengedo. A quick glance confirms this is no ordinary temple: appearing to hover like a spaceship, its tall round body has softly curved edges, a tapered base and a white concrete facade punctured with small circles and rounded rectangles for windows.

The temple fills a narrow plot among offices and hotels The ultimate 21st-century temple prototype – created by the architect Kiyoshi Sey Takeyama of Amorphe – it is no doubt the most cutting-edge of the 18,000-plus nationwide temples belonging to Japan’s popular Jodo Shinshu Buddhism sect. And its hyper-modern Shinjuku setting is no accident: its creators hope that the temple, which is open to the public and offers numerous community activities, will attract a new generation of followers. “This site is located in a busy and noisy backstreet district close to Shinjuku station,” explains Takeyama. “I wanted to cut this kind of urban context and create a calm and quiet atmosphere protected by the building, with strong form and thick concrete walls. So this temple is lifted up from the ground as if it is floating from its context.”

Sliding screens designed by Fuyuko Matsui decorate a traditional tea room

The interior concrete is precisely imprinted with planks of cedar The sound of water greets visitors, flowing hypnotically over the tiered stone surface of a tilted 6.6m-high waterfall that spans the side of the building. The lobby – more boutique hotel than temple – has smiling grey-suited staff at the reception, a wall of windows framing views of the exterior waterfall, plus a futuristic black box where visitors whose relatives are interred here swipe their smart cards on arrival. Internal walls depict the delicate grain of natural wood, with planks of cedar painstakingly imprinted onto the white concrete – a discreet feature evoking the wooden warmth of traditional temples. Lifts smoothly transport visitors to the fifth-floor apex, home to “Nyorai-do”, an intimate hall seating around 80 people for Buddhist services and concerts (a black Bösendorfer grand piano sits in the corner).Centre stage is a luminous deep-blue screen, hand-painted with lapis lazuli pigment, framing a gold Buddha statue that hovers above a cloud created by the sculptor Jun Tomita. The wall is slit with narrow rectangular windows, one of which is positioned with mind-boggling precision to allow the sun to shine directly onto Buddha’s face twice a year – at 3 o’clock on the spring and autumn equinoxes.

The exposed-concrete facade rises above a tapered base One floor down is “Ku-no-ma”, a long, narrow and 10m-high meditation space inspired by the Buddhist concept of emptiness, with minimal walls of sloping concrete and layered cypress wood, and a piece of sky viewable through a round window. To add to the meditative atmosphere, a small button hidden in wood panels to the left of the door activates an abstract soundtrack by the French musician Pierre Mariétan. Sound and water recur in “Ken-Sui”, a modern interpretation of the traditional temple hand-washing ritual by the soundscape artist Taiko Shono: visitors use a bamboo scoop to clean their hands above a metal bowl on a balcony, with the resulting overspill cascading into a cylindrical instrument on a lower level of the building, each drop creating a delicate musical note. Another highlight is a dramatically ethereal series of black etchings by contemporary Japanese painter Fuyuko Matsui mounted on sliding screens in the traditional tatami-mat tea room.

The basement includes eight booths for viewing family urns, which are automatically transported from a high-tech vault Meanwhile, spanning several floors in the heart of the building is an off-limits high-tech vault system that can hold the cremated remains of up to 7,000 people – it has already acquired more than 300 since opening last year. After visitors swipe their entrance cards, family urns are automatically transported to the altar of one of eight viewing booths in the basement, alongside electronic photographs of the deceased. For all its abstract modernity, Takeyama’s goal was simple: to create a temple that was faithful to its original role as a welcoming community hub. “Once, temples in Japan were not only a place of prayer and training, but also a school, hospital and cultural complex of museum, concert hall, library and so on,” he adds. “This project is an attempt to revive these cultural programmes in a contemporary temple’s design.” |

Words Danielle Demetriou

Images Keith Ng |

|

|

||

|

An elliptical opening in the facade allows light to enter a roof terrace |

||