|

|

||

|

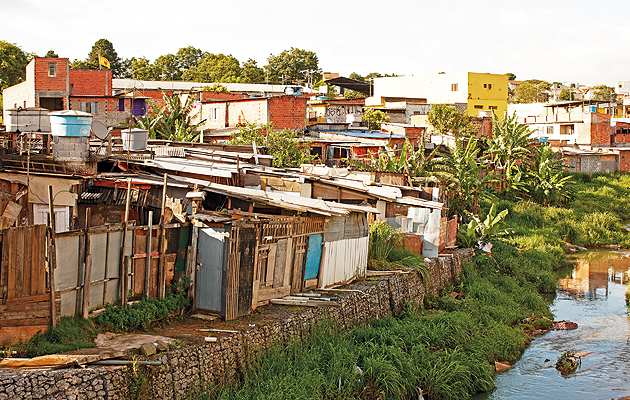

This drive-by portrait of Brazil’s largest city takes us on an anti-clockwise tour around the sprawling metropolis, exploring the ring of social housing and favelas that surrounds it – a vast area from which many residents faced eviction as the country prepared to host the 2014 football World Cup. This article was first published in Icon’s September 2012 issue: Restless Cities. Buy old issues or subscribe to the magazine for more Today, São Paulo is slowing down. The population is not growing anywhere near as fast as it used to, but all of that growth is happening in one zone: the periphery. São Paulo’s sprawling fringes reveal a city that is still very much in the making, still raw. It is a place where the sacrifices people make for access to the city are written into the landscape, into the fabric of their homes. Cities that grow this fast grow in an unconsolidated way, so, while the periphery is full of pathos, it is also full of potential. This is the record of a drive around the periphery of São Paulo. In London Orbital, Iain Sinclair spent months walking the M25, the city’s ring road, in an attempt to understand and embrace the sprawl. I have no such inclinations, and not just because the distances involved are even greater. São Paulo is not a city for walking; it’s a city of cars – 6 million of them. In that spirit, this is emphatically a drive, and as such it is an unapologetically blurred snapshot of a city taken from a moving vehicle, with occasional stops here and there to stretch our legs. But while I doff my cap to Sinclair, in one respect he had it easier: São Paulo has no M25. There are plans for a ring road, the Rodoanel Mário Covas, a 170km-long four-lane motorway. Indeed, one section of it opened in 2002, but the project has stalled. Instead we’ll be patching together our own orbital, a spaghetti of roads named Ayrton Senna and Presidente Dutra, Nordestino and Imigrantes – some of these names contain clues as to how this city grew so corpulent. Our route will take us anti-clockwise around the city. In telling the story of social and informal housing in São Paulo, we will examine the conditions that face its most recent arrivals, as well as the forms of housing that previous decades have offered. As we travel, a picture will emerge of the different strategies the government has taken to house São Paulo’s ever-growing population. But this is not just a survey of housing; it is a portrait of a city best understood by its edge condition. The São Paulo of popular imagination is conjured by photographs of a dense field of skyscrapers and tales of its helicopter-borne elite on one hand, and by a creeping fringe of favelas on the other. In the case of São Paulo the word periphery is almost a misnomer, as there is more periphery than anything else. But it would be overly simplistic to see the city in terms of a wealthy core surrounded by a ring of poverty. While migrants tend to concentrate around the periphery, they are not alone. It is a place of extremes – in the 1980s and 90s, wealthy citizens fled the inner city for suburban gated communities. Alphaville – the sprawling enclave of manor houses and swimming pools on the city’s north-west edge – is the most notorious of these. But such places are not the focus of this journey. Not only is there little to distinguish Alphaville from the suburbs of Phoenix, there is scant inspiration to be found in the capacity of the rich to look after themselves. By contrast, the tenacity of the poor in carving out a life in this brutal city is a constant source of amazement.

Self-help: São Mateus While the favela may be the most notorious form of housing that the poor will build for themselves, there are more institutional forms. In fact, we came across this favela by chance. The real reason for visiting São Mateus was to see another settlement down the road. Here, residents were granted permission from the government to build themselves real homes, following a standardised design handed out by the department of housing. This programme is known as mutirão, a Portuguese word taken from the indigenous Guarani term for working together towards a common goal. The mutirão housing programme was launched in 1987 as a cost-effective way of tackling the housing deficit. Local community organisations could claim grants for building materials, and then pool their labour to build the houses themselves. It didn’t come with legal tenure of the land, but it was a productive way of resourcing community self-organisation.

In São Mateus, more than 500 families built their own homes this way. Arranged in neat terraces along straight, orderly streets, these two-storey houses appear to self-consciously shun the disorder of the favela. But they are not without their idiosyncrasies. It soon becomes apparent that the original houses lie somewhere behind newer extensions that thrust the frontage right up to the pavement. In most cases these extensions consist of forecourts for parking with an extra room and balcony above. The owners of these houses may be poor, but in one respect they emulate their wealthier paulistano counterparts. Almost every house meets the street with a large, floor-to-ceiling gate.

The decorative panache behind each gate varies – some go for pink paint and faux-marble tiles; others, for bare brick and concrete – but the gate is universal. Introduced in the 1980s, the mutirão housing scheme was a short-lived phenomenon. It had only been running a few years when the incoming government of President Collor scrapped it in 1990. While local community housing initiatives still exist, the government-sponsored version arguably never really worked anyway. It was overly bureaucratic, requiring participants to work on the building a certain number of hours a week to qualify and it was a huge drain on families – one that did not even result in legal ownership. It was much easier and cheaper, in the end, to have a local mason build you a small house in a favela. Having briefly romanticised the idea of self-building, the government quickly resumed its laissez-faire ways. |

Words Justin McGuirk

Photographs Thelma Vilas Boas |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Journey to the edge Hitting a suddenly denser, working-class neighbourhood, it is striking how many of the walls are covered in pixação. This is a uniquely Brazilian brand of name tagging. Unlike so much graffiti, which still echoes its New York origins, this is sui generis. The distinctive lettering evokes Tolkienesque runes, as though the place is crawling with acrobatic elves. Because the higher or more inaccessible the pixação, the more bravado displayed by the pixador. It’s not uncommon to scale tower blocks, as pixação is as much an urban sport, like parkour, as an artistic expression – and it is occasionally fatal. The content of these scrawls is not political so much as the act itself. Walls, are the city’s preferred social barrier, separating not just the rich from the poor but also the individual from the very idea of that collective hell out there. And so it is only fitting that the pixadores use walls to broadcast their presence – to turn, as the sociologist Teresa Caldeira puts it, a tool for separation into one of communication. |

||

|

Rotting concrete These hulking blocks in São Mateus have the air of prisons. They are raised up on piloti, that device beloved of tropical modernism, but in every other respect their design and construction is crude in the extreme. Their sad effect is no doubt partly a consequence of their colour, the concrete shame-facedly showing through the sallow, mildewed pastels. Though they would have been built in the early 1990s, they look much older. It’s the climate that does it. Lévi-Strauss noted the rotting effect of this heat and humidity in Tristes Tropiques, concluding that towns in the New World “pass from freshness to decay without ever being simply old”. Rotting concrete is the backdrop to so many lives, as one blogger has observed. The Clã da Parede Podre, or “rotten wall clan”, blog mocks working-class paulistanos who post pictures of themselves in aspirational poses – in the swimming pool or with a flashy car – only betrayed by the stained walls behind them. It’s a nasty piece of snobbery. Anyway, it makes you realise what a coat of paint can do. One of the social-housing developments here is much newer, which is obvious not just from the slightly more complex design (with corner balconies) but the freshness of its colour. The building is almost exactly the hue of the red earth around it, as if it was formed from the very clay on which it sits. The redness of the earth here is a constant surprise to my European eyes, and while one is hardly ever aware of it in the city centre, it is abundantly exposed on the rawer edges where the city is still being formed. This redness is in some ways the very essence of Brazil. The country was named after the trees that the Portuguese called brasa, or “embers”, for the reddish glow of its wood. It was the dye extracted from that wood, and thus one might say redness itself, that made Brazil such a lucrative colony in the 16th century. |

The golden opportunity presented by Brazil hosting the 2014 World Cup is leading to old-fashioned slum clearances |

|

|

|

|

Modernism: Zezinho Magalhães Pulling into the complex of Zezinho Magalhães, its vast scale is not obvious at first, but there are three sectors and a total of 72 housing blocks. And that’s only half of what was planned. Commissioned by the military dictatorship in 1967, it was originally designed to cover 130 hectares and house 50,000 people. Zezinho was to be an exemplar of how to provide social housing on a mass scale. Vilanova Artigas, its lead architect, used it as an experiment in prefabricated construction in the hope of achieving an industrial efficiency. Mendes da Rocha, Artigas’ assistant on the project, recalls that “the goal … was to reach a level of excellence that would demonstrate that quality of housing need not correspond to the economic standards of a given social class, but to the technical knowledge of the historical moment, offering rational, honest and accessible construction to everyone.” This kind of idealistic rhetoric, still prevalent in the 1960s, has hardly been heard since. The idea that somehow technology would be a great social leveller never quite transpired. But the main reason why governments and architects alike drifted away from such noble stances on social housing was the expense. Ironically, given their often reactionary politics, in the late 1960s and 70s the military regimes of not just Brazil but Argentina, were still willing to pump huge sums of money into housing projects by the most respected architects. At this stage, high modernism still had political backing, even if it was from dictatorships to which the architects themselves were antithetical. But as it became clearer that such exemplar projects were failing to keep pace with population growth and were thus ineffectual at reducing the housing deficit, the political will sapped. It would be fair to say that from the late 1970s onwards, what was an idealistic and centralised strategy became a pragmatic and piecemeal one resulting in the kind of forlorn housing blocks we saw in São Mateus.

Flood proof: Vila Nova Pantanal We decide to pay a visit to Vila Nova Pantanal, a favela that used to have terrible problems with flooding. The government spent R$60m ($30m) on drainage and other infrastructure, and is rather proud of what’s been achieved. We know this because when we get there, we pull up in front of two billboards advertising this as the work of the government of the state of São Paulo, with the state insignia looming large. A sign like this is necessary, I suppose, because a drainage system is not an especially visible or photogenic improvement. To that end, a cosmetic intervention was required. The house fronts themselves have been painted in a clashing combination of greens and pinks, now resembling the pick’n’mix bucket at the sweetshop. The paint was donated by a paint manufacturer as part of its corporate social responsibility programme. But while the colours are one thing, the wave patterns tip this makeover into uncomfortable kiddies’ playtime territory. There’s something worryingly patronising about it.

Favela: The reservoirs São Paulo didn’t have a masterplan until 1971, when the military dictatorship decided that the city should be densified into the endless towerscape that is its hallmark today. But the plan didn’t include the periphery. Here, settlers would be allowed to fend for themselves, in a state of tolerated illegality. As urbanists Mariana Fix and Pedro Arantes put it, the favela “was a clandestine model, with the state’s consent; a form of solving the housing problem at low cost, without urban and civil rights”. In 2001, the Statute of the City finally gave favela dwellers those rights, or at least the right to remain. While they do not own the land they live on, they are no longer illegal squatters. But do they enjoy what Henri Lefebvre called “the right to the city”? Are they equal citizens with the same access not just to basic infrastructural and social amenities, but also to the opportunities and rewards of urban life? Clearly not. The problem is not just that they are poor but that they are literally excluded, which is a more radical barrier than poverty. And that exclusion is spatial, not enforced with walls and fences as in the case of Alphaville, but through a lack of infrastructure. Basic city services – it might be public transport or running water, sewerage or electricity – stop at the borders of favelas. In more senses than one, they are off the grid. Cariocas – residents of Rio de Janeiro – label this dichotomy the morro (the hill) and the asfalto (the asphalt). It is a truism that favelas tend to be founded along creeks or riverbanks – and in hard-to-reach areas that developers wouldn’t normally touch, hence their availability. The Guarapiranga and Billings reservoirs are São Paulo’s sources of drinking water, and it is a cause of no small anxiety that they are rimmed with favelas. At least 700,000 people live around Guarapiranga, pouring millions of litres of untreated sewage into the reservoir every day – a situation that is more egregious during the floods. Here, the housing deficit starts to impinge on the formal city. The planners face a classic debate: should these favelas be moved or should they be given proper infrastructure, which will only encourage more informal residents to pitch up? In Paraisópolis, for instance, there are signs that such a strategy is in effect. But elsewhere it’s business as usual. The golden opportunity presented by Brazil hosting the 2014 World Cup is leading to old-fashioned slum clearances. Since our drive, thousands of people have been or are under threat of being evicted from areas such as Itaquera, where a stadium is being built. There is little doubt the mayor and governor will write off mass evictions as collateral damage in the Fifa-led development drive. Welcome to São Paulo: politics as usual. Edge City: Driving the Periphery of São Paulo, of which this article is an extract, was published by Strelka Press |

|

|

|

||

|

|

||