|

|

||

|

Any lasting impact will be to tourism and gentrification rather than the impoverished favelas, says Will Henley On 5 August Michel Temer will declare the 2016 Olympic Games officially open. He is Brazil’s acting president and reportedly behind an impeachment process that saw elected president Dilma Rousseff removed from office in April. Temer represents the return to power of an old elite who have capitalised on an economic recession and a corruption scandal at state oil giant Petrobras. Amid this turmoil, and with just days until the opening ceremony, venues are unfinished, Guanabara Bay remains too polluted to host its proposed sailing events, and the Zika virus threatens to keep athletes away altogether. Just when it seemed that things couldn’t get worse, on the day the Olympic Torch was lit, a recently inaugurated £8 million cycle path collapsed into the sea, killing two. This must be a bad omen for an event that will be judged on the lasting impacts of its architectural and urban legacy. The Olympics is just the latest in a series of mega events in the cidade maravilhosa, following the 2007 Pan American Games and the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Despite the array of transformations, notable improvements in transport and some innovative architecture, the broader picture is of an opportunity wasted to redefine a unique city in which dramatic topography allows luxury condominiums and favelas to exist side by side, but where integration remains all too distant. |

Words Will Henley

Images: Matthew Stockman and Leonardo Finotti |

|

|

||

|

Christ the Redeemer overlooks Guanabara Bay |

||

|

Rio has adopted a dispersed model in which four development zones are linked by a series of new highways, named the Bus Rapid Transit system. In addition, an extension to Rio’s paltry metro network takes visitors from the tourist hubs of Ipanema and Copacabana to the main site to the west of the city. In theory, this strategy should improve access and spread advantages across the city, softening Rio’s pronounced inequalities. However, the vast majority of investment has been poured into a greenfield site west of the centre in Barra da Tijuca where the principle venues and athletes’ village follow a masterplan by UK giant Aecom. Hugely wealthy developer Carlos Caravalho is behind a real estate development that caters only to Rio’s elite. This will eventually be marketed as a tourist resort named Ilha Pura (the Pure Island) – a name which boasts of its isolation from the complex reality of a divided society. Luiz Fernando Janot, professor of architecture at Rio’s Federal University, has criticised a confidential tendering process that led to this proposal at an early stage. He adds that this search for a new El Dorado west of the city turns its back on an increasingly impoverished commercial centre yet to recover from the removal of state functions to Brasilia. This situation has been intensified by the present economic crisis. |

||

|

The Youth Arena by Vigliecca & Associates |

||

|

The principal central site, characterised by historic factory buildings has been dubbed Porto Maravilha (the Marvellous Port). A motorway flyover has been removed to encourage the regenerative scheme, which includes the construction of Santiago Calatrava’s Museum of Tomorrow, as well as another museum. These institutions add to the area’s existing cultural activity, kickstarted by the occupation of the Bhering chocalate factory by artist collectives. This semi-derelict complex is now alive at weekends with street food and impromptu music – an atmosphere surely the envy of the now polished warehouses in Shoreditch. But as with east London, the likely rise in property values that is bound to follow the area’s designation as a creative district must be managed to incubate these activities. Mayor Eduardo Paes’s purchase of the Behring factory in 2013 was a promising sign. Yet, the surrounding historic buildings are crumbling, and will need further preservation if the area is to deliver on its promise. |

||

|

The Bhering factory in Porto Maravilha, now home to artist collectives |

||

|

Morar Carioca was perhaps the most exciting of the pledges that won Rio the contract. This ambitious proposal promised to deliver essential infrastructure to 260 favelas by 2020. Yet the project has stalled, meaning the plans to sanitise the waters feeding into Guanabara Bay, many of which pass through favelas, have failed. The spectacular bay may be home to the photogenic Sugar Loaf Mountain, but its sewage-filled waters make it a poor host to sailing and open-water swimming. The 2.5 million sq m Deodoro site is the largest Olympic zone and has been sensitively placed in Rio’s poorer Zona Norte – another world from the city’s glamorous beaches. It hosts a range of events whose venues have been integrated into an existing site built for the 2007 Pan American Games. After the games it will become a public park. |

||

|

The polluted waters of Guanabara Bay |

||

|

The project is masterplanned by São Paulo based Vigliecca & Associates, which recently gained international acclaim for a social housing complex in Santo Amaro. The high point is its Miesian Youth Arena, which will host the women’s basketball; the legacy proposal removes internal seating to create a multi-use sports venue. This sensible investment caters to the nearby military base, whose occupants were responsible for 48 per cent of Brazil’s medals at the 2015 Pan American Games. However, the most sophisticated legacy idea comes from the handball arena on the Barra site. The venue has a lightweight steel structure, and is clad in a delicate recycled timber screen. These elements are almost entirely demountable and destined as the basis for four municipal schools. This transitory and mutant architecture, says Gustavo Martins, principal of designer Oficina de Arquitetos, was a feature of the competition brief and the delivery of the schools forms part of the construction contract. However, the school sites are yet to be confirmed and this latter stage is vital for the project to succeed. If the fate of London’s Olympic stadium is anything to go by, this is unlikely to be straightforward. Efforts to reinvent London’s centrepiece were hampered by a protracted bidding process for use of the venue, resulting in costly design changes. |

||

|

Santiago Calatrava’s Museum of Tomorrow, a central element of the Porto Maravilha regeneration |

||

|

But this growing trend for adaptive solutions represents an alternative to the short-termism of recent high-end architecture demanded by Olympic committees – think of the Bird’s Nest now lying empty in Beijing or the disaster of Athens’ abandoned Olympic park. Perhaps equally disappointing was the treatment of Rio’s once legendary Maracanã stadium by FIFA. Here, exacting design standards stripped the venue of its history and significantly raised ticket prices. A more radical architectural approach can be found within another of Rio’s recent mega-events. The Pavilion of Humanity, designed by Carla Juaçaba and Bia Lessa for the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development, was a temporary structure in place for just 15 days. The dramatic 40m-long pavilion, suspended above Copacabana’s fort, shows that such structures need not compromise on inspirational design quality. |

||

|

Carla Juaçaba’s temporary Pavilion of Humanity, built in 2012 |

||

|

Arena Carioca 3 and the Olympic Velodrome at Barra |

||

|

This focus on venue strategy must not deter us from thinking about the wider implications of mega events. The widespread failure to deliver urban improvements to Rio must surely make our patience with the Olympic excuse increasingly short; the ideal of smooth completion must no longer disguise the transfer of public wealth to private construction companies. The onus must now be on the International Olympic Committee to respond and adapt its processes, particularly when dealing with countries with a history of corruption. A look at the preparations for the 2024 Summer Games shows the clear importance of venue legacy in the IOC’s selection criteria for host nations. By contrast, there are no specific references to urban design. Rectifying these priorities would be a step towards the rehabilitation of perceptions. |

||

|

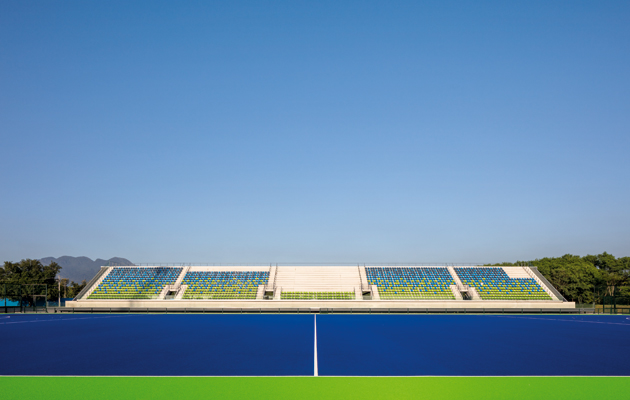

Vigliecca & Associates’ hockey arena at Deodoro has 2,500 permanent and 5,300 temporary seats |

||