Casa de Musica in Porto. Photo by Philippe Ruault

Casa de Musica in Porto. Photo by Philippe Ruault

Controversial architect Rem Koolhaas is as much a creator of ideas as he is buildings

Called a Deconstructivist by some and a Modernist by others, Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas has been given many names, including recently that of an ‘anti-architect’ after he claimed that the built environment may have no effect on the contentment of the humans who live within it. He began his career as a journalist before studying architecture, and his attitude of investigation and an aptitude for writing has stayed with him throughout this career.

He co-heads the Office of Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) and AMA, the research branch of OMA, with a declared purpose to address contemporary society and build architecture that fits the present modern. Since the 1990s, Koolhaas and OMA have built projects across the world that redefine what contemporary architecture can be. From the Casa da Musica in Porto with its vast window behind the orchestra, to the pivotal Seattle Central Library, Koolhaas has been a hugely influential force on the way architects look at cities.

Koolhaas founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) in London in 1975 with Madelon Vriesendorp and Elia and Zoe Zenghelis.

De Rotterdam. Photo by Ossip van Duivenbode

De Rotterdam. Photo by Ossip van Duivenbode

Koolhaas was born in Rotterdam in 1944. His father was a writer, theatre critic and film school director and moved the family to Jakarta, Indonesia for a job posting when Koolhaas was eight. When he returned to The Netherlands, he studied journalism and began his career at the Haagse Post. He later attempted scriptwriting and had a short but productive career in film before studying architecture in London.

After he graduated from the Architectural Association of London, Koolhaas wrote a seminal book called Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan, published in 1978. It is still regarded as one a groundbreaking volume. In it he celebrates ‘cultural congestion’ and looks into the potential creativity that can be born in dense, vertical cities. Koolhaas look at this density as a catalyst for creativity – a place where spontaneous interactions lead to innovation.

In his book he also introduces his ideas about cross-programming, where he outlines the advantages of bringing the unexpected into the programming of buildings and developments, for example running tracks inside skyscrapers and hospital wings in library buildings. Koolhaas also published S, M, L, XL in 1995, summarising the work of OMA in what he calls a ‘novel about architecture’. It is made up of seemingly random thoughts, plans, photos, essays and fictions.

Seattle Central Library. Photo by Philippe Ruault

Seattle Central Library. Photo by Philippe Ruault

Koolhaas brings the idea of cross-programming into many of his designs, although they are not always fully accepted by the clients. The Seattle Central Library for example, was built without his suggested hospital for the city’s homeless. Koolhaas has always been interested in the city as the domain of extremes within the human experience.

The Seattle Library, even without the full scope Koolhaas intended for it, has had a radical impact on the way spatial relationships are used by architects. The buildings pivotal planes give the users different views of the city and act as an example of how sophisticated forms can be derived from a focus on the user experience.

The Netherlands Dance Theatre in The Hague embodied many of the ideas Koolhaas had presented in Delirious New York. The volume was made up of various forms and materials put together in unique combinations to create a visually intriguing composition and new typologies of space. The plan had three zones – the stage and its thousand-seat auditorium, the rehearsal studio, and a small zone that housed offices, dressing rooms and common areas. It was completed within an impressively small budget, and the building escalated OMA’s rise to international acclaim. Erected in 1987, was demolished at the end of 2015 to make way for a larger theatre complex.

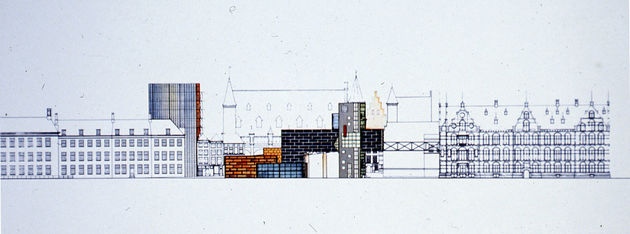

Parliament sketch. Image courtesy OMA

Parliament sketch. Image courtesy OMA

Since then, OMA has worked on highly conceptual buildings, including the proposal for the Dutch Parliament Building in The Hague, which they entered into an international competition. During the 1990s, Koolhaas and OMA tackled projects of various scales, from notable private residences to the patchwork masterplan for the Euralille development in northern France.

The residential projects were partly influenced by Modernist buildings, but Koolhaas made the properties highly customised the clients needs and requests. Villa Dall’Ava in Paris is a glass house with a swimming pool on the roof. It features a floating glass pavilion containing shared living and dining areas with two, hovering perpendicular apartments that exploit the view and stand on an irregular network of columns.

The highly praised Maison Bordeaux was designed for a couple who’s house had become a ‘prison’ after the husband was confined to a wheelchair. He wanted a complex house, knowing that it would define his whole world and Koolhaas created a dynamic three-storey complex connected by a spacious elevator that also serves as a private office space.

Villa Dall’Ava. Photo courtesy ESTO

Villa Dall’Ava. Photo courtesy ESTO

Koolhaas tested his theories about urban life in the large Euralille development in the outskirts of the northern French town of Lille. It comprised a new shopping mall, conference and exhibition centre, and office towers and is linked to a new high-speed rail line. Koolhaas wanted this new development to have the depth and texture of an old city, so created a world of mismatched and overlapping urban attractions. He commissioned different well-known architects to design the different buildings while he himself designed the convention hall, which was named Congrexpo.

In the last decade Koolhaas has focused his attention on striping architecture down to its fundamental elements. As the director of the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2014, Koolhaas even themed the event ‘Fundamentals.’ He has also become somewhat of sceptic, announcing that people will be miserable or contented at random in any environment, regardless of the architecture.

Koolhaas and OMA still participate in many international architecture competitions, as the process allows for creative freedom without the imposing will of the client. It comes with a certain amount of financial risk, time and money invested into concepts that will never be built, but Koolhaas believes the experimentation it offers is worth it.

Netherlands Embassy. Photo by Christian Richters

Netherlands Embassy. Photo by Christian Richters

As a young architect, Koolhaas taught at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, where he met and taught Zaha Hadid. Dhe came to work for him at OMA and they collaborated on a series of highly conceptual projects, including the Dutch Parliament Building, before Hadid left to set up her own studio. Koolhaas is also a professor at Harvard University.

Koolhaas continues to publish controversial work, pushing the boundaries of how architects look at interaction within space. He is a philosopher-cum-architect, and will no doubt continue to push forward radical designs in built and conceptional worlds. One of the most important urbanist of his generation and was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2000.

Watch a film about Koolhaas by his own son