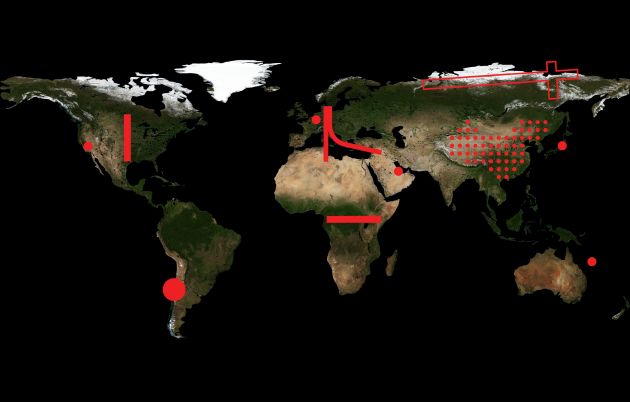

AMO’s selection of unique and highly specific conditions distributed over the globe serves as a framework for their research. Image: Courtesy of OMA.

AMO’s selection of unique and highly specific conditions distributed over the globe serves as a framework for their research. Image: Courtesy of OMA.

Although guilty of priortising text over exhibit, AMO’s ambitious Guggenheim exhibition Countryside, the Future carries some important warnings, finds Tim Abrahams.

By opening an exhibition about the countryside in the heart of Manhattan, Rem Koolhaas has been judged by a jury of his inferiors of both having his cake and eating it.

He’s been on thin ice for a while. One of contemporary architecture’s greatest critical voices, he began his career as a thinker by exploring the real architectural character of modernity in Delirious New York (1978), and went on to explore its shortcomings in books like S, M, L, XL (1995) and Junkspace (2001), all the while developing his side hustle as one of the world’s most successful architects. This was already hugely problematic for those who couldn’t make it in either field, but with Countryside, the Future – a major revaluation of his own critical position – Koolhaas has quite simply gone beyond the pale.

The exhibition is light on objects and heavy on text. Photo: Laurian Ghinitoiu. Courtesy of AMO.

The exhibition is light on objects and heavy on text. Photo: Laurian Ghinitoiu. Courtesy of AMO.

The exhibition is an attempt to rebalance the urban fixation that has dominated not just the architectural profession but also the political and sociological sphere for the last two, possibly three decades: a process in which Koolhaas himself admits he has been complicit. It might be beneficial to momentarily set aside his conviction for simultaneous cake ownership and consumption and look clearly at what has been produced. Countryside, the Future is certainly not an easy exhibition to love. It is interested in neither art, nor actually in architecture. And in the spirit of the dense presentations of AMO – the research wing of Koolhaas’s practice OMA – it emerges from the techniques and discourses of sociology, economics and the much unheralded but increasingly essential field of geography.

Objects are too rare in the show. Yes, at the 5th Avenue entrance, amongst the hired limos idling outside condo blocks, a huge technologically advanced tractor sits incongruously. Inside though, it is only at the culmination, atop the Guggenheim’s spiralling ramp, that we come into contact with genuine artefacts.

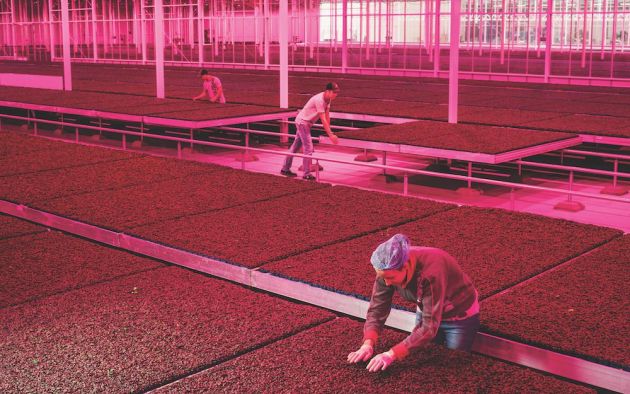

The exhibition explores the changing conditions of rural labour. Photo: Pieternel van Velder.

The exhibition explores the changing conditions of rural labour. Photo: Pieternel van Velder.

In an exhibition which purports to address an overlooked condition, namely the planning and optimal use of rural space, this is an oversight. The exhibition begins inauspiciously too, with a large drape printed with apparently random statements from the vast cultural legacy of our thinking about the countryside as a pastoral idyll, which leaps forward centuries to how this now informs the wellness industry. This is too simplistic, we fear.

Yet this is just a clearing of the throat, belying the huge range and depth of the work beyond. In the Guggenheim’s bays divided by Frank Lloyd Wright’s elegant fins, Koolhaas has installed a series of investigations into different rural conditions around the world. The insane story of how Qatar created its own agricultural sector on the day a Saudi Arabia-led blockade cut it off from its usual food supplies is just one example. Stephan Petermann’s research into how Alibaba is turning villages in China overnight into specialist manufacturers, connecting producers directly with customers, is another frankly awesome case study on how the rural world is changing at pace. Researchers from the University of Nairobi exploring how M-Pesa – a financial transaction system which uses mobile phone numbers rather than bank accounts – is radically altering the potential of Kenya’s rural entrepreneurs. Koolhaas offers a biennial of the new non-urban economy.

Installaation view of Countryside, The Future at the Guggenheim, New York. Photo: David Heald. Copyright: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Installaation view of Countryside, The Future at the Guggenheim, New York. Photo: David Heald. Copyright: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Yes, it may be may be scrappy and be guilty of that age old criticism of being a book on a wall. And it may be arrogant for Koolhaas to tell us what’s going on in the countryside given his role in trumpeting the moral values of urban congestion. Yet if one casts a glance over our cultural world, no-one since Raymond Williams has noted how the positive values of modernism – the ability to plan and provide; to rationalise and improve; to organise logically – are failing everyone except those who live in the core of a handful of global cities. We are not offering improved livelihoods to the people who live beyond. Instead there is resentment, or if we are lucky, a kind of ad hoc modernity, captured well by the exhibition, which all too easily flickers and is gone.

AMO has drawn on examples of rural industry and development from across the world. Photo: David Heald. Courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

AMO has drawn on examples of rural industry and development from across the world. Photo: David Heald. Courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

The frankly spiteful way that Koolhaas’s words have been received in some quarters says less about him than his detractors. It is a familiar attitude. The Gilets jaunes emerged when a rural and suburban workforce in France were asked to pay for the environmental policies of Macron’s government and thus found their livelihoods threatened. They took to the streets to protest, and Macron and the French establishment traduced them as fascists, while outside observers like the British establishment treated them with derision. In the UK, we decry the neo-Georgianism of new housing in exurban sites without once thinking of how our lukewarm modernism was re-established around the late 1990s by treating everything beyond the urban core as inferior. We reject the message and insult the messenger. At some point we are going to have to accept that Koolhaas and others have a point – and that we are making a mistake by ignoring them.