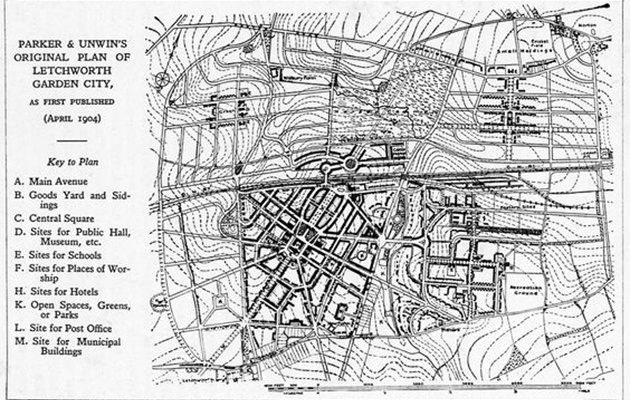

Parker and Unwin’s original plan of Letchworth Garden City, 1904.

Parker and Unwin’s original plan of Letchworth Garden City, 1904.

After reading about social housing architect Peter Barber on Icon 179, one reader felt compelled to write in. Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier might be symbols of ‘total planning’, but British planners are just as worthy, writes John Astley.

‘I was interested to read Will Wiles’ piece on Peter Barber in ICON 179 but disappointed that while citing Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier with regard to ‘total planning’ he omitted to say anything about British contemporaries. Lloyd Wright (born in Wales of course) did draw extensively on the Arts & Crafts movement, and I would mention two other equally inspired planners/architects, Raymond Unwin (1863-1940) and his brother-in-law Barry Parker (1867-1947). They both drew on Arts & Crafts values in general, and specifically in the realm of planning, design and architecture (a ‘complete’ design approach) for example drawing on the vernacular styles of a local environment, using materials to hand, and with a clear focus on function over form. They were close to Ebenezer Howard, and his Garden City ideals, working with him on Letchworth, the first of the garden cities.

By 1901 Unwin and Parker published The Art of Building a Home where the emphasis on a home rather just a house should be noted as this reflects the high value they placed on meeting the needs of ‘real’ people. They advocated and incorporated all the latest techniques, and were committed to an aesthetic that promoted curved roads with grass verges and trees, the cul-de-sac, integral parks and green spaces, allotments, public buildings like community centres, schools, workshops and so on. In 1902 Unwin published a Fabian Society tract Cottage Plans and Common Sense where he lists basic requirements; size, light, furniture, garden etcetera that were fit for purpose. This was a period when designers of housing for working people actually included a kitchen and bathroom, in addition to a scullery. Unwin and Parker also argued that when planning an ‘estate’ there was ‘nothing to be gained from overcrowding.’

Unwin’s desire to be involved in the creation of new ‘communities’ (still a contested concept) reflects his definition of a community as a free association of individuals, with harmony between people and their environment. The design planning values of Unwin and his contemporaries certainly drew on William Morris’ 1880s novel News from Nowhere.

After his early collaborations Unwin was lured in to a more back office role with the Ministry of Health as an advisor. Parker carried on with his architectural practice. It should be remembered that before and after the 1914-18 War public health was a key social policy priority, and up to and including Aneurin Bevan in the 1940s, the minister of health was also the minister of housing. Perhaps it is time now to return to that link? In 1909 Unwin had published his Town Planning in Practice which was influenced by one of his European contemporaries Camillo Sitte, and it is worth reflecting upon just how successful were/are the German ‘garden’ towns and suburbs. I would certainly suggest that Unwin like others was influenced by Walt Whitman’s ‘democratic’ vistas, and led him in his design values to an imaginative grasp of parallax, which in this sense means those curved roads mentioned above, with houses set at unexpected angles to each other to draw the eye and the person along and through unfolding spaces.

One of Unwin’s innovations at the ministry was to collaborate with the publication from 1919 of a fortnightly journal Housing, which set out to offer practical help and advice for the benefit of councils, architects, designers in general, builders and so on. The journal included designs, layouts, tips on how to overcome common place problems, and a support network for all, but particularly for those interested in and involved with the public sector.

In the period between 1918 and 1939 there were numerous reports and housing acts ‘homes fit for heroes to live in’ and all that, but perhaps the most important report was the Tudor Walters report of 1918 that made the recommendations for design and building standards that was to push successive ministers of housing to take action. For me the most significant of these ministers was John Wheatley, minister of housing in the first Labour Government in 1924. His Act was the first to incorporate all the recommendations for design and standards with a major focus on subsidies to Local Authorities, councils, to build houses for working people, which included a commitment to rescuing families from slum conditions.

Unwin and Parker had many contemporaries in planning, design and architecture, not the least of course being Patrick Abercrombie and the Liverpool School. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century there emerged an increasingly dominant social democratic ideology that sought to shift power away from the comfortable private sector for meeting welfare needs like housing, to a public sector engagement with meeting the needs of the majority of people in a fair manner.’

John Astley is the author of 2012 book Access to Eden on arts and crafts design and architecture, the garden city movement and housing policy legislation.