|

Only a citizenry informed about architecture and cities can lobby for the kind of communities they want, says the Philadelphia Inquirer’s architecture critic after receiving the prestigious journalism award Inga Saffron of The Philadelphia Inquirer has won this year’s Pulitzer Prize for criticism – becoming only the seventh architecture critic to receive journalism’s most prestigious award. Saffron’s interest is in the context and social impact of buildings and the relationships between communities and the built environment. In writing her column, Changing Skyline, she draws on her background as a news reporter to rail against development that she feels diminishes the social experience of a city – from inner-city parking lots to “garage-fronted townhouses”, which she says make cities less friendly and safe – and argue for positive transformation such as the redevelopment of the dead space on Philadelphia’s waterfront and funding for public transport. The Pulitzer jurors described her work as blending “expertise, civic passion and sheer readability into arguments that consistently stimulate and surprise”. We spoke to her about the award. Congratulations on winning the Pulitzer. It’s a fantastic personal accolade, but what do you think this award means for architecture criticism as a whole? Thank you. I think it’s great that the Pulitzer jury has chosen to focus on this aspect of criticism. When you go to a movie or an exhibition, you make a choice to do so, but when you walk down the street you don’t have a choice about the buildings you see, how they’re designed – and that affects your mood, your day. I think the decision is a reminder of the importance of this speciality. There have been many cuts recently at newspapers and this might be seen as an area papers can no longer afford, but I’d like to think I’ve made it relevant and that this prize might make other newspapers and media think about having their own architecture critics. You’ve been writing your column for the Philadelphia Inquirer since 1999. How do you think the role of the critic has changed since then – especially with the rise of blogging? When I first started seeing everyone online writing about buildings – and all this “rendering porn” – I got a little depressed. I thought, “how can I keep up, I’m only one person”. But, over time, I realised that there was nobody making sense out of all this information. Despite a zillion websites devoted to architecture and design, there’s very little devoted to real commentary and making an argument about what’s important. That’s what a critic does – they take all the information and explain why it is important. That’s the value of point-of-view journalism – to make sense of the vast amount of information that comes into our brains every day. That’s what I try to do – and that’s why I think it’s important for general interest newspapers to have someone do that. There’s so much development in our cities right now – in the US and UK – and many websites take everything at face value, as if it were all the same. You need to have people who can stand up and say, “no this is not good development”. Having a paid staff job at a newspaper gives you a certain independence and freedom to say those things, in that I’m not dependent on the goodwill of developers – so I’m quite lucky.

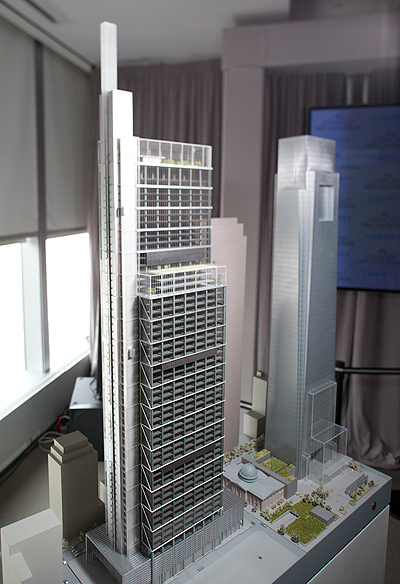

The model of Norman Foster’s tower for Comcast Critics can play a role in informing people, shaping public opinion and instigating change. What is your aim? I think my role is the same as any other journalist: that is, to provide information so citizens can make decisions to help democracy function. I’m perhaps an unusual hybrid. I was a reporter for many years – a foreign correspondent – so I come from a news background, even though I studied art history and have spent a lot of time in different cities. Because of this, I do a lot of reporting. I seek out not just what’s been presented to me by a developer, but speak to a whole range of people. My goal is to provide context so citizens can understand why a project is good or bad and how it will affect them. We need a citizenry that’s informed about architecture and cities and how they are made so they can lobby for the kind of communities and spaces they want. City building should be collaborative – between people who use the cities, those who build the buildings and politicians. But do you think there is an increasing distance between those who use buildings and those who build them? If so, what can be done about it? Absolutely. Developers have so much power and money drives so much of what gets built. Money also drives politics – and this is a huge problem in American cities, where there’s much less government support for the public realm [than in Europe]. It’s said that developers run New York City and you could also say that about Philadelphia. That’s another reason we need independent voices – it’s only an informed and organised citizenry that can pressure elected leaders to push back against moneyed interests. And that’s a huge ongoing struggle. |

Interview Debika Ray |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

You have a specific interest in the repopulation of cities in the US. Could you tell us more about that? In the US, the history of the past 60 years is an amazing arc. In the 1960s and 1970s, huge numbers of middle-class people left the city for the suburbs, and you were left with a concentration of poverty and abandoned land and property. Terrible things were done to cities during this time – downtowns were levelled, great buildings were lost and there was a huge amount of disinvestment in transit. Starting in the 1980s, and accelerating over the past 10-15 years, a new generation of millennials who have no memory of those terrible times are being drawn to cities for a number of reasons – because of the internet, opportunities for social interaction and dissatisfaction with sterile surburban life. We’re seeing all sorts of people come back to cities and rebuild, and the middle class is growing, so people want cities to be more liveable and equitable. This is a great thing – the repopulation of cities – and now there’s more political interest in this phenomenon. Because of this, I spend a lot of my time writing about the issues that have resulted in new interest in urban life. All the big policy issues of our day come back to cities and how we construct them – how we are going to live, how are we going to help the environment and save the planet and how we are going to innovate. So I don’t just write about architecture from an aesthetic point of view without any of this context. I always situate design in these larger social policy issues.

I95: A huge interstate highway that cuts off historic Philadelphia from the Delaware waterfront You sound optimistic about the future of cities. But what are some of the challenges facing urban centres that you think are most pressing? In developing nations, where they have huge populations, the question is how to house them quickly – how to make houses, as well as the quality of life on the street and public spaces. I was in Mumbai a few years ago and in cities like that finding the right scale of housing is a major issue Another challenge for those fast-growing cities is not making the same mistakes we’ve made in the West, in terms of favouring the car. These two issues – housing and transit – will dictate how liveable and sustainable these cities are. In America, we don’t have those densities – we have so much land relative to our population – so our issues are a little different. What role do you envisage for the public sector in tackling the problems of cities? Well, in the US we practically don’t have an urban policy – that has been a problem for years, both on a state and national level. We don’t have investment in transit and everything takes a million years to build. Philadelphia has a great transit network, but it’s inherited from the days of private operators and there’s been virtually no addition to the system for 30 to 40 years. We don’t even have electronic fare cards because the system has been so criminally underfunded. And this is not just Philadelphia – in New York, a much wealthier city, doesn’t have nearly as much investment in transit that it ought to. Politicians in the US are very far behind in appreciating this change that’s occurring – the number of people returning to cities and the value of cities and concerns about the environment. We need out elected officials to catch up with the pressure to do that.

A typical Philadelphia parking lot Finally, what is your proudest professional achievement? I’ve certainly written a few stories that have prompted design changes or projects to be reconsidered. But I take the long view – hammering progressive issues changes the conversation over time. For example, in Philadelphia I was writing about the lack of development on our waterfront for years at a time when sea officials were happy to just pave it over and built big box stores. I argued against that – and for housing, public space and trails. Initially people made fun of me, but eventually the city did a masterplan and people who shared my view joined the conversation. Now there’s a completely different attitude to the waterfront. I also used to be seen as a crazy person because I was so anti-parking garage. I still beat this drum all the time: that we’re going to need to learn to live without the car and that we can’t tear down parts of our city to house these big pieces of metal – the trade-off is a bad one. But I think I’m seen as a little less of a crazy person now when I talk about that. It’s a slow process of introducing ideas that ordinary citizens wouldn’t normally be exposed to. People who are in architecture, design and urban policy know these issues, but I’m not speaking to them – I’m speaking to people who’ve never heard these ideas. You can read some of Saffron articles on the websites for the Pulitzer Prize and the Philadelphia Inquirer |

||