The revival of postmodernism is more than next-generation nostalgia. It reflects a society, economy and entire political system in a profound state of flux writes Owen Hopkins

Postmodern architecture died in New York City early on the morning of 8 January 1979, or thereabouts, when the first copies of that week’s Time magazine hit the newsstands, emblazoned with a besuited vision of Philip Johnson clasping a model of his AT&T building.

Or so someone might have written. What radical postmodernism then possessed as a credible, critical force surely evaporated the second the great architectural chameleon of the second half of the 20th century served it up in debased, caricatured form to be devoured by the great monster of commerce.

Yet postmodernism regenerated and was swiftly reborn. Every time it has died again, even when we think it has gone for good – for example when Robert Venturi declared, ‘I am not now and never have been a Postmodernist’ – it has come back with a vengeance.

After nearly disappearing from view in the 1990s and early 2000s, postmodernism is back once again, as architects and designers look afresh at its ideas and aesthetics, and historians and critics reappraise its legacies.

We see this particularly in the Netherlands, where postmodernism arguably never went away, but also in London, where it makes a welcome break from the unrelenting dullness of the New London Vernacular. Notable examples include DK-CM’s Barkingside Town Square, where the practice created a new loggia as a flattened 1:1 replica of the adjacent modernist library’s clerestory windows; AOC’s Nunhead Community Centre, with its bright colours and herringbone brickwork playing on those of a mock-Tudor pub next door; and David Kohn’s extension to a Victorian house in north London that elegantly and unmistakably channels early Venturi.

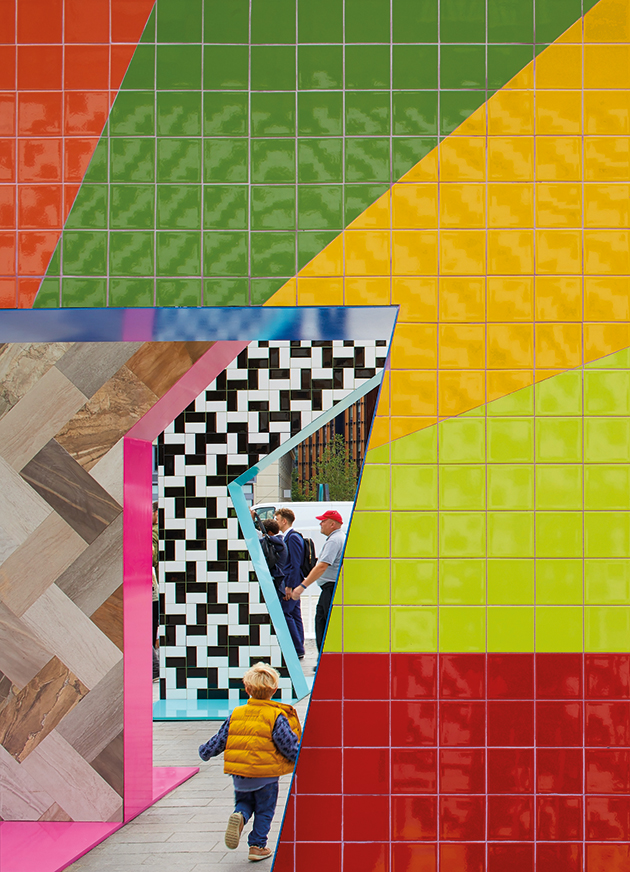

Even somewhere as mired in earnest ‘good taste’ as Argent’s development north of King’s Cross has seen the recent arrival of Morris+Company’s millennial pink R7 building, and Adam Nathaniel Furman’s Gateways project, which became the defining image of last year’s London Design Festival.

Furman has, of course, been a notable advocate for colour and exuberance in architecture. Yet his is now far from being a lone voice as a growing group of students and young architects discover the possibilities of quotation, ornament and style.

For several years now, Waterloo-based Alma-nac has been building a reputation for an eclectic body of work, including the recent The Upside Down House (which is exactly as it sounds) for a playground in Reading. In London, CAN’s recently completed Lomax Studio uses two distinct volumes to represent the different scales of its occupier’s work in a piece of postmodern double coding par excellence. And Studio MUTT, which won attention for its playful Ordnance Pavilion in the Lake District, followed Furman in staging its own colourful project at Sir John Soane’s Museum for 2018’s LDF.

The question is whether this trend is attributable simply to the turning wheel of taste, of architects looking to differentiate their work from that of the preceding generation, or does it reflect broader changes in architecture, design and the world in which they operate? The answer, I argue, is firmly towards the latter: the postmodernist revival reflects a society, economy and entire political system in a profound state of flux.

But what is the postmodernism currently being revived? Is it simply style or something deeper? For some commentators, postmodernism actually began at the same time as modernism, there at its heterogenous beginning lurking in the shadows, before finally reaching centre stage as modernism wore itself out in the 1970s. In even more abstract terms, we might see the modernism/postmodernism dualism as running even deeper, as one of order vs disorder, singularity vs pluralism, simplicity vs complexity, minimalism vs maximalism, and so on – present in all periods and in all societies.

While postmodernism may be a reflection of a universal sensibility, what emerged in the 1960s and 70s was equally tied to a very particular set of political, economic and social conditions. Postmodernism was the cultural manifestation of Jean Baudrillard’s concept of ‘hyper-reality’: the speeding up of reality that had resulted through consumerism, TV, the proliferation of images and an inability to distinguish the real from its simulacrum or image.

Although there is a definite postmodern style – like the test for obscenity in the famous US Supreme Court case of 1964, we know it when we see it – it is far more than simply aesthetics. Postmodernism is a cultural movement that has manifestations in everything from philosophy to art, social studies and even geography. And in this regard, it was a profound breaking away from what had come before. For Jean-François Lyotard, one of its most influential theorists, the advent of postmodernism was the condition that had resulted from the way that ‘in contemporary society and culture … the grand narrative has lost its credibility’.

No longer could human history be conceived as part of a gradual journey towards some specified future end state. The Enlightenment idea of progress, of the onward march of history towards universal human emancipation, and the belief in the transcendent value of rationality, science and technology were all under threat in the new age of post-industrialisation, consumption, de-urbanisation, globalisation. None of this now fitted with the aspirations of modern architecture, particularly where it had been aligned with the discredited politics of social democracy and the welfare state. As the most visible of these ‘grand narratives’, modern architecture came under attack from all quarters.

For the critics Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, writing in Collage City, published in 1978, but deriving from earlier work, ‘one definition of modern architecture might be that it was an attitude towards building which was divulging in the present that more perfect order which the future was about to disclose’. It is therefore of some irony that much of so-called socially ‘progressive’ thinking in architecture today is actually looking to the apparently halcyon days when 50 per cent of architects worked in the public sector, and notions of the public good were rather easier to define.

One of the rather perplexing, though also instructive, things about the postmodernism revival is the way that it follows the recent resurgence of interest in brutalism. At least a part of the brutalist revival directly relates to present social and political concerns, notably the housing crisis, with those on the political left looking at an era when the state provided housing for all and recasting brutalism as its most radical embodiment. In this context, postmodernism is brutalism’s antithesis: light, ironic, the epitome of 1980s individualism and the politics of ‘there’s no such thing as society’.

While one would be hard-pushed to detect a brutalist revival in architecture – clients, it seems, are still put off by the perceived dystopian connotations of raw concrete – there are similarities in why we are looking again at these two very different styles, notably that the generations leading the reassessments are those too young to have been indoctrinated against them. But it is surely obvious that the reassessment and revival of postmodernism comes from a quite different place to that of brutalism.

Or maybe not. While some are drawn to brutalism for its inferred social and political underpinnings, for the much larger group of revivalists it is really about aesthetics, and the moody black-and-white photographs of raw concrete that are readily shared online. Shorn of its social and political agenda, the aestheticisation of brutalism is really just an act of postmodernism, which after all was not a rejection of modernism but, in the word used by its foremost architectural theorist, Charles Jencks, its ‘transcendence’.

Just as postmodernism originally emerged at a time of political and economic transformation, of one system – neoliberalism – supplanting the mixed economy of the post-war years, its revival is evidence that we are undergoing another transition. Whether one calls this the fourth industrial revolution, or the emergence of a post-capitalist economic order, we are currently witnessing neoliberalism’s supplanting by a new post-work, post-digital economy built around automation, sharing and the blurring of physical and digital realities.

Pluralism, disorder, complexity, contingency – all postmodern attributes – are the cultural consequences of social, economic and political flux. We saw it in the 1920s with the advent of modernism as a series of competing ‘isms’, we saw it again in the 1970s and 80s with postmodernism, and it’s what we are seeing now.