|

|

||

|

John Outram’s psychedelic plans for a huge hotel Battersea Power Station, derelict for more than 30 years, has been called a graveyard of architectural visions. Icon visits the practices responsible for some of these fantastical, unrealised schemes – by John Outram, Nicholas Grimshaw, Ron Arad and Terry Farrell – and talks to Wilkinson Eyre about its latest ideas The only time I’ve made it inside Battersea Power Station was for a Björn Borg underwear launch during London Fashion Week 2012. Not traditional Icon fare, but the ruin porn location was too good to resist. Lots of Scandinavian models clad in glow-in-the-dark underwear frolicked in the hulking red brick wreck, whose roofless nave had been transformed into a snow-covered pine forest for the evening. We drank champagne and slurped oysters, looking up the weathered walls of the gutted boiler house at the four looming chimney stacks, which glowed cream in the moonlight. Robyn and Coco Sumner performed songs, while the models braved the February cold to parade up and down in their luminous pants, have mock-cheerful pillow fights and sit self-consciously in bubbling hot tubs. When we left the industrial wasteland, we were gifted our own radioactive drawers. The power station, the largest brick building in Europe, was decommissioned in 1983. It now seems odd that London’s infrastructure – Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s masterpieces at Battersea and Bankside – were so prominently placed on the southern shores of the Thames, billowing symbols of national pride rather than grimy polluters to be hidden away. Built in the 1930s (with a further two chimneys and the turbine hall added in the 1950s), Battersea Power Station is as tall as a 22-storey building and boasts one million square foot of space. A cathedral of industry, it could easily swallow St Paul’s whole. But since it stopped production, the grade II-listed London landmark, immortalised alongside a flying pig on the cover of Pink Floyd’s 1977 album Animals, has always presented an awkward, expensive, almost cursed challenge to developers. A plethora of colourful, imaginative schemes have come and gone over the past three decades making the power station, according to one headline, “the graveyard of architectural visions”.

Peter Legge proposed a museum of industry First, the Central Electricity Board held an ideas competition, won by Peter Legge and Associates’ proposal to make Battersea a museum of industrial heritage (Terence Conran would later call for it to become a museum of design to rival the Tate Modern). Exhibits on the Great Fire, the space age and the Blitz would have filled the voluminous turbine halls. In the gardens outside would be reconstructions of Crystal Palace and the Euston Arch, alongside which the SS Great Eastern would have been moored. However, nothing came of these plans and, in 1986, Battersea Power Station was sold to John Broome, the impresario behind Alton Towers. He proposed turning the structure into a massive, indoor playground: “A 1980s hybrid of Disneyland, Alton Towers and Tivoli Gardens,” according to one contemporary report. Fitzroy Robinson designed a hyperactive theme park that included a skating lake, a parachute drop, golf driving ranges and a rollercoaster.

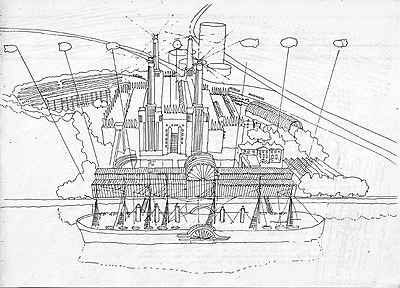

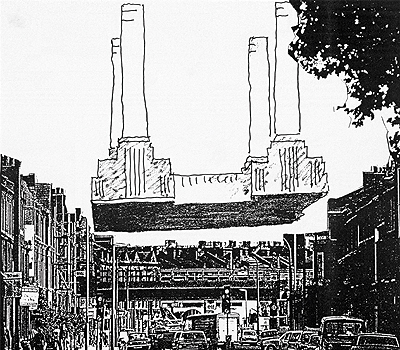

Fitzroy Robinson’s theme park The scheme was to be a high-tech “Fun Palace” of the kind Cedric Price hoped to build in London during the 1960s. Two years earlier Price had submitted his own radical ideas for the monolith, suggesting only the redundant chimneys and their steel supports be kept. The brick walls of the structure would be removed so Battersea’s famous silhouette would appear to float on the London skyline like an upturned table, enabling new housing to be built in its shadows. English Heritage would never have gone for such a scheme, but the alternative did little to protect it. Broome, who anticipated an optimistic 3.5 million visitors to his theme park every year, took off the power station’s roof so the antique machinery and 4,000 tons of toxic asbestos inside could be easily removed.

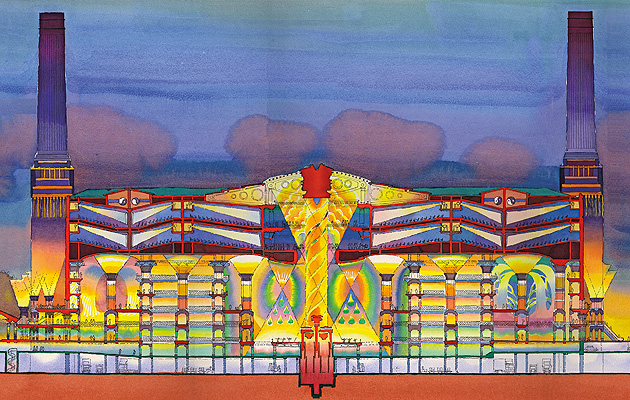

Cedric Price’s proposal to keep only the stacks (image: Cedric Price (CCA) In 1990, however, the scheme was abandoned due to escalating costs, which bloomed from £35m to £230m, and the hollowed-out core, with its art deco details, fell into disrepair. The steelwork was exposed and the foundations damaged by flooding. In 1993, Victor Hwang and his Hong Kong-based company Parkview International bought the power station. Hwang had been impressed by the building as a 12-year-old public school boarder (“You just didn’t see things like that in Taiwan,” he said), It was his restless vision that produced another burst of ambitious, fantastical schemes for Battersea. “He has a reputation for consuming architects the way others have meals,” The Times reported in a 2000 profile, commenting on Hwang’s revolving door of collaborators. His tenure at Battersea was his architectural education, one of these architects told me, and he got a thrill from having architects pitch him drawings and models of their proposals – it was almost as if they were court jesters jobbed with entertaining him. In a series of striking, acidic polychromatic drawings, John Outram imagined a massive 700-room hotel, with wind turbines on the chimney stacks. Arup created a masterplan for the site, with another hotel that swept around the building that you could climb from the riverside park as if up a massive staircase. Nicholas Grimshaw was tasked with devising a scheme for the voluminous interior, initially intended to be a cinema multiplex and permanent home for Cirque du Soleil.

Arup’s hotel swirls around the Grimshaw scheme Ron Arad was employed to come up with a hotel of unparalleled luxury that would span between the chimneys on the roof. When I met him in his Camden studio, Arad described what was to be called the Upper World as his “beautiful failure”. Budgeted at £35m, it would have been his biggest ever project. “The developer wanted us to do something absolutely unique,” Ron Arad Architects’ director Asa Bruno says. “There was very little restriction in terms of brief or budget. The hotel had only 44 rooms, most of which were 150sq feet, and would be the most expensive in London, upwards of €3,000 a night.” As VIPs drove up to the entrance, a moving screen would shield them from the paparazzi. A lift in one of the chimneystacks would bring them to a two-storey lobby. A horizontal, glazed shuttle would then take them to their maisonette room, with its private plunge pool on a balcony overlooking London. With a nod to John Broome, a turbine was to be installed in one of the chimneys so skydiving could be simulated. A chimney would also function as a huge luge, and an exclusive “table for two” restaurant was planned atop another stack. Arad’s scheme was dropped in 2005, but in Alfonso Cuarón’s futuristic film Children of Men, released the following year, the power station (which had become a museum of looted art) was rendered with a gently vaulted roof and skylights as though the idea had been completed.

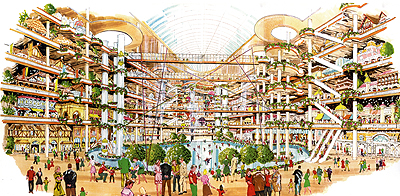

Arad’s rooftop hotel included a bullet train The next scheme that caught Hwang’s imagination was a proposal by Grimshaw partner Neven Sidor to leave the roof of the boiler room off, retaining the dramatic views of the ruin. The core would be completely renovated, with escalators leading up to two “grazing platforms” on top of the turbine halls, which would include floors of shops, cafes and restaurants modelled on nearby King’s Road. It was an assertive intervention that didn’t detract from Scott’s architecture. We’ve all got our list of favourite unbuilt projects that are all better than anything we’ve ever built,” Sidor says, “and this is one of mine, definitely.” English Heritage insisted on a roof, and an inflated ETFE one was added to the proposal. Hwang then asked Arad to come up with a sculptural piece to fill the central void, a spiralling ramp in bright red that would link the many separate levels while obliterating views of the iconic chimney stacks. “Victor liked craziness,” Sidor sighs. “We weren’t crazy enough for him – he thought we were too earnest: he needed a bit of Mad Max in there.”

Grimshaw proposed leaving the core open to the elements Hwang, who had his site office in Toyo Ito and Cecil Balmond’s 2002 pavilion, a white cube made of intersecting triangles and trapezoids that he bought from the Serpentine Gallery, never developed any of these schemes because, Sidor says, “he got bored so easily”. He also liked playing his architects off against each other. Ron Arad’s rooftop hotel, for example, asserted itself as the architectural statement of the power station, which irritated the Grimshaw team. And every other building Hwang planned for the rest of the 32-acre site, now masterplanned by Arup’s Cecil Balmond, had to be iconic in itself. Buildings with names like The Crystal, The Twist and The Weave – by UN Studio, West 8 and Gustafson Porter – competed for attention with the power station and each other. In 2006, Hwang sold the site to Irish investor Treasury Holdings, pocketing £200m in profit. Cynics suspected he’d just been sitting on the real estate, and had never planned to build there at all.

Viñoly’s tower, three times as high as the station’s stacks Two years later, Rafael Viñoly revealed his £4bn plans for the 32-acre site, which he packed densely with snaking cliffs of offices, retail and housing. As part of this plan, the developer would contribute to an extension of the Northern Line to bring the needed crowds to Nine Elms. Viñoly’s scheme included a riverfront development just to the east to be capped by a huge, glass “Eco-Dome” and a 300m-high “chimney” that would supposedly ventilate the office buildings below. This stack was three times the height of the power station. “You have to bet the farm,” Viñoly explained cryptically of this egotistical addition (a year later the controversial tower, a pre-recession gesture no one was convinced would actually work, was removed from the scheme). The power station itself was to be protected by a moat, turning it into a fortress of sorts (like the new US embassy just upriver), and its turbine halls transformed into a series of shopping malls. However, by the end of 2011, after gaining planning consent from Wandsworth Council, the developer went bust. Again, the power station’s future hung in the balance and the site was put up for sale on the open market for the first time. Terry Farrell submitted an idea to preserve it as an elegiac ruin, inspired by Fountain Abbey, proposing to knock down the turbine halls and turn the screen walls of the boiler house into an open colonnade that echoed Scott’s constant repetition of verticals. The area inside Viñoly’s moat would become a wild garden, while the listed control rooms would be left exactly where they are now, housed in two raised Miesian boxes overlooking the site.

Farrell proposed turning the ruin into a park “It’s so expensive to fit out and restore, and a tremendous burden on any developer,” says Farrell partner Neil Bennett. “We thought the true memory of Battersea Power Station would be best served by preserving it as a shell rather than filling it up with unsatisfactory office space.” It would have been a poetic attraction, a welcome rustication at the heart of a massive new development. Their idea, which didn’t satisfy heritage requirements, was not shortlisted, unlike a competing scheme on behalf of Chelsea Football Club, which felt it had grown out of its Stamford Bridge stadium, that proposed turning the site into an altogether different green space. In 2012, a Malaysian consortium won the bid – Chelsea would have to stay put.

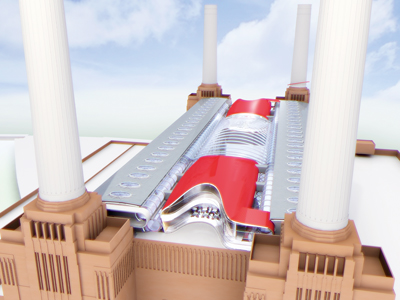

The Viñoly masterplan with moat They chose to retain Viñoly’s masterplan, with its moated icon and surrounding buildings by dRMM, Frank Gehry and Foster. Wilkinson Eyre, which is refitting Scott’s 1930s Bodleian Library at Oxford University, is to transform the interior of the power station. The two turbine halls will be given over to retail, with escalators and balcony walkways on each level, and the boiler room to a huge auditorium, whose red belly will fill the space like a bloated Anish Kapoor, with six floors of offices above.

The turbine halls will be devoted to retail A glass elevator will take punters to the top of a chimney, where they can look down at the two floors of apartments on the roofs of the turbine annexes and the luxury, gated housing community above the boiler room, where Arad’s hotel was to be. Wilkinson Eyre director Jim Eyre tells me these homes will go for up to £10m, with advance sales helping to fund the project.

The boiler house with its six floors of office space I ask him how he’d prevent Battersea Power Station from looking like a Westfield shopping mall, and Eyre is at pains to emphasise the shabby chic he hopes to retain in the finished building, much of which is lost in the renders submitted to his Asian clients. The cranes “There will be a connection between the new content and the sort of distress of the existing building, which we quite like – we’re not trying to clean it up particularly,” Eyre says. Their scheme is due to get detailed planning consent at the end of April, when the developer will have to pay its share of the Northern Line extension before the first of the station’s white towers can be demolished and rebuilt. Of all the attempts to “save” Battersea, it looks the most likely to be realised. But it hasn’t happened yet.

Wilkinson Eyre’s gated community on the roof |

Words Christopher Turner |

|

|

||