Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Yellow Still Life, 2021

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Yellow Still Life, 2021

Words by Vasia Rigou

Situated by the sea on Kuusisaari island in western Helsinki, lies Finland’s Didrichsen Art Museum, a fascinating space that blurs the lines between public and private – think tranquil sculpture gardens complete with a pool, sophisticated interiors that include a sauna, an aquarium and large floor-to- ceiling windows that let the outside in. Here, art, architecture and nature peacefully coexist.

Originally the home of art collectors Marie-Louise and Gunnar Didrichsen and their four children, it was brought to life in two phases (1957 and 1964), both designed by a Finnish architect of the functionalist school, Viljo Revell, who was widely known for the design of the Lasipalatsi and Palace Hotel in Helsinki, as well as the city hall of Toronto, Canada.

His work masterfully weaves elements of modernism, rationalism and concrete brutalism together telling a unique story – one that Elina Brotherus could not disregard. Splitting her time between Helsinki, Finland, and Avallon, France, Brotherus has been working in photography and moving image since the early 1990s.

Her signature move: telling intimate stories by turning the camera to herself. Identifying three important sources of inspiration: art history (namely the recent art history of Fluxus, feminist avant-garde and the like), literature and architecture, she is striving to achieve an equilibrium between ‘the more objective conceptual thinking of art-making and its histories, combining it with the emotional and personal,’ as she puts it.

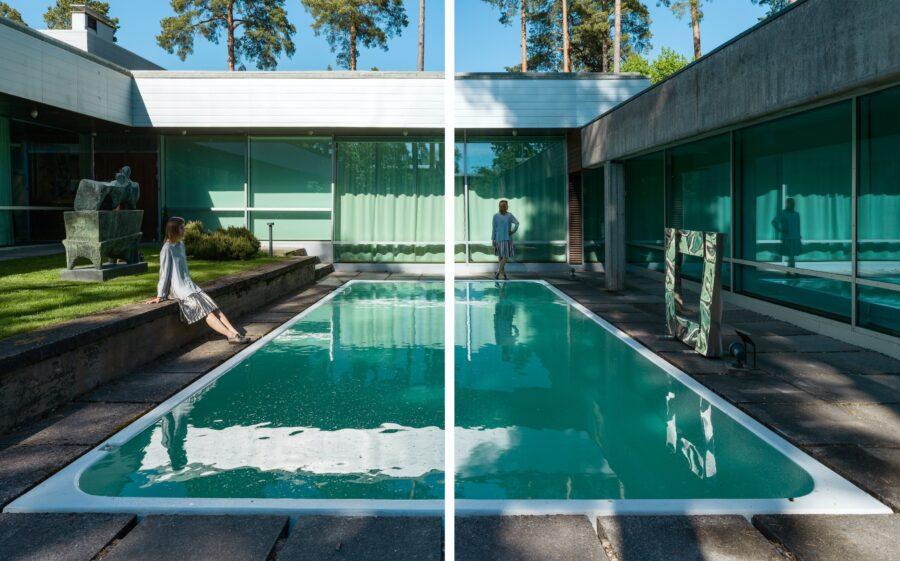

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Swimming Pool, 2022

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Swimming Pool, 2022

‘Art follows life,’ she says. ‘As an art student in the 1990s, I used my personal experiences as the starting point for work. I put an end to my previous studies of science as well as to my first marriage. This sudden liberation became visible in my images. After moving abroad, I became interested in the iconography and the expression of painting. I continued to see myself as a model, but now I was an image-maker instead of an autobiographer,’ she adds.

‘As I approached 40, autobiography returned through the back door. It wasn’t planned, but I didn’t push back either. My strategy as an artist is to accept the images that need to happen. Since I have no children, I am always the youngest in the family. This allows for playfulness and freedom, qualities that I appreciate more and more as I get older. I don’t have to represent the traditional way of being a woman. I can give the middle finger to the norm.’

Brotherus is used to using her own figure in the image. ‘It has become like a word in my visual vocabulary or my trademark, if you will,’ she says. ‘As time passes, it’s interesting to follow the evolution of this familiar figure from the young artist in the 1990s into the middle-aged woman of today. I hope I can continue to work until very old age. It would be wonderful to juxtapose in an exhibition my 25-year-old self and my 85-year-old self.’

Within her work, Brotherus feels more often as an object than as a subject. ‘I consider my body to be a compositional element that brings a human presence to the space,’ she says, deeming it necessary to detach herself from the pictures. ‘I often speak about “that woman in the picture” but never about “me” or “Elina”,’ she says, explaining that ‘photographs suggest; they don’t provide an indisputable truth about anything and they tell as much about the observer as they do about their author’.

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Carrying Gottberg, 2022

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Carrying Gottberg, 2022

She reminisces about her very first encounter with architecture: ‘I was invited to work in the Maison Louis Carré outside Paris, which is designed by Finland’s most famous architect Alvar Aalto. It was a big surprise how much living in that house affected me – even though I only stayed there for a few days. The experience changed my attitude towards architecture, from indifference to admiration.

It was the first chapter in an ever-growing series on domestic architecture – the Villa Didrichsen is the latest,’ she says. ‘I call the project Iconic Houses, and I wish to photograph in different countries, in buildings of exceptional architectural quality that were designed to be family homes.’

What Brotherus didn’t know at the time, was that museum director Maria Didrichsen had the exact same idea. ‘I was invited to Maison Louis Carré to talk at a seminar and had the fantastic opportunity of spending the night in the house,’ she says.

‘When I saw Elina’s photos of that place it blew me away! Our museum is designed by architect Viljo Revell, who was Alvar Aalto’s colleague, and they share some similarities in their designs. Both houses have a pool, too! So, I thought it would be a fantastic parallel, if Elina one day would photograph herself in our space.’

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Piscine (Transat), 2018

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Piscine (Transat), 2018

So Brotherus did just that. Shot in the Didrichsen Art Museum’s space, her latest exhibition Visitor (also including a selection of work from the past 20 years – a nod to what remains constant throughout her career) hopes to direct a contemporary gaze on architectural past. ‘I wish to give a new visibility to exceptional domestic architecture that audiences are not used to seeing,’ she says, stressing the importance of well-designed and aesthetically ambitious spaces for one’s wellbeing.

‘A house is a home,’ she says. ‘However, if you think of architectural photography, the pictures are always empty. My architecture work is different because I introduce inhabitants into the houses. The characters I evoke could have lived there in some parallel history. Or perhaps they have been there – as visitors, neighbours, far-away cousins, friends. They occupy the space at their calm discretion. They do what people do at home: eat, sleep, contemplate, read, take showers, have tea. They help the spectator to enter the space and they suggest possible narratives.’

‘In the case of the Villa Didrichsen, a lot of pictures of the family exist, so it’s clear my character is not one of the immediate family – hence, a visitor. The woman in the pink bathroom with a Hockney glitch must have stayed for a sleepover. The one in green who carries a green painting is perhaps a visiting curator. The orange figure in the library with Kandinsky’s Murnau painting is closest to a self-portrait. The clue is in the book that I’m taking from the shelf. The title is The Fortunate Wanderer. I think that’s me!’

Offering a glimpse into her creative process, Brotherus dives deeper: ‘Working in a house has something similar to doing a portrait of a person – you have to discover and show the core or the essence of them,’ she says. She goes on: ‘Every house has its key. At Villa Didrichsen, it’s the art collection – it’s great! And everyone there is very cool to work with. Can you imagine any other museum that allows the artist to walk in and start to curate their walls? I studied the catalogue raisonné and I could select anything I wanted. I made a yellow still life, a green still life, I did Picassos, I did all my favourites from Chagall and Kandinsky to Rothko and Rauschenberg… It was really something. I enjoyed it tremendously!’

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Kitchen Telephone 2, 2022

Photography by Elina Brotherus featuring Kitchen Telephone 2, 2022

‘We offered her free rein to curate something from our collection,’ Didrichsen weighs in. ‘Normally the interiors are what they are and one cannot change anything. But in that case, we decided otherwise. We used days when the museum was closed or the time between exhibitions for these setups. This is why the project has taken more than a year, but it is also why we have different seasons in the images (winter, summer etc.).’

She adds: ‘In some images she seems to be visiting the museum, in some she has taken over the space as if it were her own. She has also taken photos in spaces that are not often visited by outsiders, for example the family kitchen. We reorganised it in a 1950s atmosphere, and I just love these images! She is like the mother of the house, talking on the phone and peering into the original oven to see if the meringues are ready – just like Marie-Louise Didrichsen (the museum founder) in her time did.’

‘We need art in difficult times,’ concludes Didrichsen, who is hoping that Brotherus’ tranquil and peaceful view of the world will have the same effect on others. Between the real and the imaginary, Brotherus has learned a lot about herself and her work. ‘It’s very intuitive,’ she says. But what makes her photographs particularly important is their ability to evoke curiosity and emotion.

‘We spend too much time in rather mediocre spaces: apartments of no particular interest, public spaces constructed with cheap materials and trivial planning,’ says Brotherus. ‘I hope that through my work people will wake up to the importance of good architecture, like I did.’

Elina Brotherus – Visitor is open now and runs until 28 May 2023 at Didrichsen Art Museum

Read more in ICON 210: The Finland Issue or get a curated collection of architecture and design news like this in your inbox by signing up to our ICON Weekly newsletter