|

|

||

|

For the past 12 years, the Pritzker laureate has been working on a cluster of museum buildings that lead to a disused zinc mine in a remote part of Norway. Icon visited the construction site, and the architect’s Swiss studio, to learn why the project has taken so long and how it’s edging towards completion We walk through the narrow gorge along an old path that clings to the mountainside, high above a fast river, crossing precarious bridges that have been all but destroyed by avalanches of boulders. Eventually we reach the cave-like entrance to the old mine. We splash through

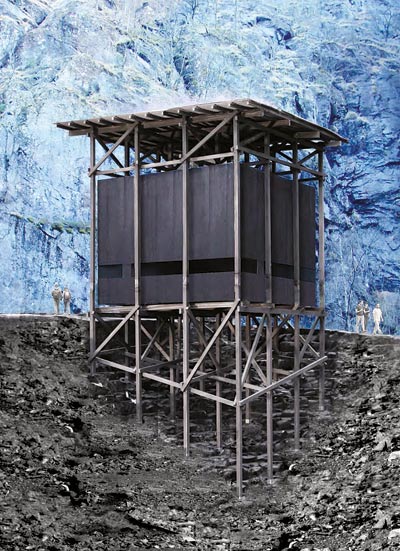

The steep site of the museum building

Zumthor’s model of the museum Between 1881 and 1899 various speculators sought to mine zinc in the Almannajuvet ravine near Sauda, a remote steel town in south-west Norway situated at the crux of a fjord that cuts deep into the interior. At its height 170 people worked here, blasting and digging out ore that was shipped to Swansea in Wales. But the deposits soon dried up, and the gaunt, makeshift mine buildings, with their roofs of birch bark and turf, eroded back into the wild landscape. In 2002, the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor was commissioned as part of Norway’s Tourist Route initiative to create a small museum and cafe at Almannajuvet, in the hope of attracting more tourists to the isolated region. However, the £9.5 million project has been beset with problems: firstly, there was Zumthor’s legendary perfectionism – Swiss anality, without Swiss punctuality. The surrounding mountains also began to crumble; their faces had to be stabilised with a mass of long metal pins, and landslides of bulky rock needed clearing – a Sisyphean task. For safety reasons, Zumthor was forced to reposition two of the four timber buildings he planned to dot along the old mining path. In the interim, the Pritzker laureate was invited to build another structure at the northern tip of the Tourist Route, a cocoon-like memorial he completed on the Arctic island of Vardo – in collaboration with the artist Louise Bourgeois – to commemorate the 91 witches burned at the stake there in the 17th century. (When I visited in 2011 [Icon 102], I was told that the mining museum would open the following spring – this has now been pushed back to 2016.) The designs of Almannajuvet’s constellation of buildings share obvious similarities with the Steilneset Memorial, which was inspired by the fish drying racks found in that area. All have cambered, corrugated zinc roofs and timber frames, in which enclosures appear to be suspended.

The zinc window frames are bespoke

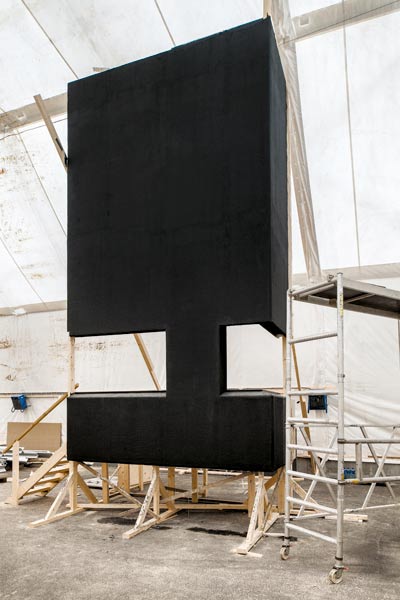

The structure is assembled in a huge tent But in Sauda’s granite, mossy landscape, studded with birch and pines, they will perch on the steep mountainside, a feat of complex structural engineering that results in dramatic, vertiginous views. The four structures will sit above and apart from the mine’s archaeological remains, but echo the ghosts of these buildings by alluding to early industrial architecture. Zumthor, who commissioned a history and plan of the site, told me that he wanted the buildings to look like they had always been there. Scaffolding is now in place, a huge stonewall has been built, and foundations dug. Ribs of creosoted pine point skywards, awaiting the structures that will slide into them almost like matchboxes. These are currently being constructed on the Sauda waterfront in huge tents, the sort that might cover an archaeological dig. They will eventually be taken by lorries up the serpentine mountain road and craned into place. One tent contains the toilet block, which will be cantilevered over the river from the granite wall, like a medieval battlement looming over a castle’s moat. A full-scale mock-up of part of the cafe building stands beside it, an example created by Zumthor’s studio to show contractors exactly how the wooden walls should be covered in hemp cloth and then painted in black tar. Early sketches showed these wooden cabins stained cobalt blue, but Zumthor eventually preferred the rugged, textured pitch finish first seen on his 2011 Serpentine pavilion. The heavy zinc doors and corrugated roofs make obvious reference to the history of the mine. Everything is designed to be jigsawed together on site with millimetre precision; every detail, including the furniture and fittings, is bespoke.

Scaffolding outlines the future cafe

A 1:1 mock-up of a corner of the building It is often said that working with Zumthor, now 71, requires Job-like patience. His Norwegian clients seem to have it in spades. Knut Wold, consultant and curator to the Norwegian Tourist Route, explains Zumthor’s process of constant refinement: “Regardless if it takes one more year, it must be the best possible. He always questions if there could be a better way. And he never gives in – he never surrenders to people like us. They’re waiting on site, the people with the cranes, but he won’t go ahead until he’s sure it’s right.” The development of the zinc-plated doors, with their rough, forged handles, consumed two years – no Norwegian factory could produce them quite to standard, and construction couldn’t be start until the door frames had been decided. Zumthor spent another three years agonising over the size and layout of the cafe’s kitchen island. His obsessive attention to detail even saw him create the recipe for the beef and vegetable soup that will be the only fare on offer; he also got involved in updating the designs of the local knitwear to be sold in the small souvenir shop. “This is Zumthor quality,” Wold says. “That’s how the process is.”

A model with bunker-like windows

Rolls of hemp to cover the structure Zumthor has apparently agreed to speak to me by phone but, an hour before our conversation is due to take place, I’m told that he has decided not to break his strict rule of only doing interviews face-to-face. Instead I’m summoned for an audience at his home and studio in Haldenstein, a small village in the foothills of the Alps, two hours by train from Zurich. There, to the sound of the lowing of cattle, 30 young architects, who have come from all over the world to learn from the reclusive master, toil over models – never computer renders – of Zumthor’s various projects. There is the house in Devon he is designing for Alain de Botton, the pillars of which are arranged like a Neolithic stone circle (“Apparently it will be finished!” the writer says, when asked for a progress report); and another for the actor Tobey Maguire in Hollywood, with a pool and roof the shape of an artist’s palette. The largest scheme is a campus for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), a blobby, Hans Arp-like plan apparently inspired by the nearby tar pits. The museum is raised on a forest of columns, accessed by the sort of elegant, spiralling ramps favoured by Oscar Niemeyer. Model makers are studding Wiltshire Boulevard with miniature palms, with fronds made of ripped brown paper. Zumthor’s atelier, currently split between two adjacent buildings, has never been bigger. Another four-storey studio is being designed to accommodate an expanded staff.

A model of the building’s toilet block

The building is assembled off-site Dressed in bleached collarless linen, and with cropped white hair and beard, Zumthor has the aloof air of a Zen priest. We sit in his monastic concrete and glass house, looking out from his office on to a courtyard of wild flowers that resembles the garden within a garden

Creosoted pine for the scaffolding

A cambered stone wall is in place Zumthor commissioned three books about the mine, mining and the geology of the region that are to be displayed in the museum building alongside a few surviving relics: a wooden clog, the head of a pick axe, a lamp, a shovel. The real museum, Zumthor says, is the mine, and visitors will be taken down it in groups by local guides (the last building on the path will contain a line of zinc lockers containing hard hats). Drawing comparisons with his memorial in Vardo, he describes his building as a monument of sorts to the workers who lived and died there. His aim is to get people out of their cars and to create moments of pause that ground them in a sense of history and place. Why, I ask, has the project taken so long – almost as long as the area itself was actually mined? “This has to do more with the Norwegian rhythm,” he responds, with a dismissive wave of the hand. “They have a slow pace there. We could go on and on – it’s nice that they didn’t pressure, but actually, now we all think, let’s finish this. I would have liked it to be faster. At first it was OK, but I am now pressing to complete it.” “I don’t want to be slow,” Zumthor explains of his uncompromising method, taking a sip of his cappuccino. “I’m a fast thinker, and I don’t want it to take more time than it takes. But sometimes it takes a while to develop something, you have to make samples and mock-ups, sometimes it takes time to find out what the building really wants to be. I imagine my buildings so completely, I unconsciously live in them. And all of a sudden I feel, hey shit, something’s wrong. There’s this corner that doesn’t work or whatever. That’s the artistic process. It’s grounded to artists, and it should also be grounded to architects who work like building artists. This is not slowness, this is just working like an architect-artist. This is how I need to work and I need a client who understands it, and wants it, and knows that this can get on your nerves sometimes.” “The finished building,” he adds, with a chuckle, “is your best argument.” This article was first published in Icon 133: Underground, under the headline “Waiting for Zumthor” |

Words Christopher Turner

Photography Andrew Meredith

Above: Tunnels in the Almannagjuvet mine |

|

|

||