|

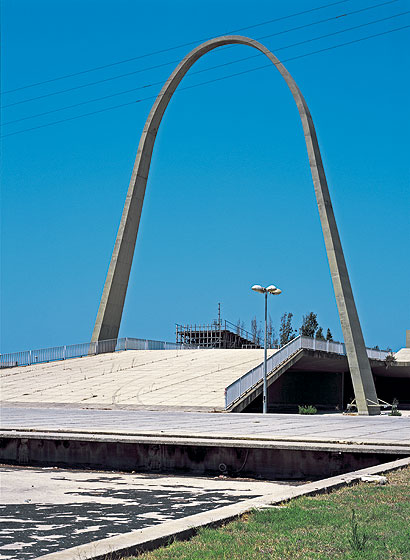

Oscar Niemeyer’s International Fair in Tripoli, northern Lebanon, was intended as the foundation of a new city quarter, but civil war intervened and it was never finished. Half a century on, its mysterious geometric forms stand like a modernist Shangri-La Last March, when I was visiting a friend in Beirut, I came across the startling news (startling to me, anyway), that in 1962 Oscar Niemeyer was commissioned to build an International Fair in Tripoli, in northern Lebanon, but it was left unfinished when the civil war broke out in 1975. Niemeyer has always been my favourite architect for his sensuous, daring forms in reinforced concrete. But although I had seen plenty of images of Brasília, the futuristic capital he designed with Lúcio Costa for Brazil and, more recently, an auditorium in São Paolo with a swirling red ramp that opened in 2005, I had never seen any of his buildings in person. Niemeyer was invited by the Lebanese government to design a permanent International Fair complex for Tripoli. He was chosen for his facility in designing buildings in warm climates and also, as a card-carrying Communist, for his politics. Niemeyer’s Brasília vividly expressed the cultural pride of a developing nation. His ambitious plan for Tripoli proposed a new city quarter including zones for commerce, sports, entertainment, and housing, with the fair at its centre. Early one morning I went to Beirut’s Charles Helou transit station, boarded a large, air-conditioned bus, and headed north. Tripoli is distinctly more traditional than Beirut: there were far more women wearing hijabs, and billboards were emblazoned with the face of Saddam Hussein or Hasan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah. It also has a subtle, tarnished elegance not found in the high-rolling capital: sweet shops with marble interiors displayed neatly stacked squares of delicacies in glass cases. The souks are riddled with tight, congested little alleyways covered with peeling ceilings and full of people shopping for all manner of things, from spices to hair dye to gold necklaces. A ruin is defined by disuse but more often by the wear and tear of centuries, so it was something of a shock to go from the 14th-century shopping bazaars to hallucinatory structures that seemed frozen in time. Lebanon is littered with ancient buildings, including Byblos, which was founded around 5,000 BC and is commonly referred to as the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. But none of the ruins I saw quite prepared me for the International Fair. The contrast between the medieval souks and Niemeyer’s modern-tropicalist Shangri-La was striking. Niemeyer’s iconic geometric forms could be seen through a tall chain link fence, scattered across the grounds like toys left behind by a toddler. A massive mound, an angular tepee, a towering cylinder, a slender arch, and a hovering disc were some of the distinct shapes that stood out. Although it is only minutes away from the centre of the city, it felt infinitely remote. Each of the eerie, empty structures is stranger than the last. The tepee was dank and pitch-black inside. Inside the mound, stiff pieces of rebar dangled from the ceiling, originally intended to secure acoustic tiles in what was supposed to be an auditorium. The tiles were never installed so a whisper can resound across the vastness. A fairly conventional building surrounded by archways was full of graffitied anarchy signs and English phrases such as “First Rule: No Rule”. Against all common sense I climbed the shaky spiral stair leading to the circular platform, which appears to be a helipad and has no railing. From here – standing a safe distance from the edge – there is a panoramic view of the site. The large footprint is shaped like an oval and is bordered by the Mediterranean coastline. Niemeyer’s original idea proposed that the individual pavilions would be housed under a single flat, curved canopy, 750m by 70m. As part of the fair Niemeyer also conceived two types of housing – one a tall building of several storeys, the other a single family villa. A “little train” would transport people through the site. There would also be an experimental theatre, an open-air theatre, and a space museum – the rail-less helipad-structure. “A space museum!” Lebanese architect Makram el Kadi exclaims when I ask him about the fair. “That in itself is a weird thing to have in Lebanon.” As a visiting professor at Yale, El Kadi gave his students Niemeyer’s plan as a studio assignment to reconsider, rework, and complete. El Kadi is based in New York and Beirut and, along with Ziad Jamaleddine, is one of the principals of architecture firm LEFT, which built the Beirut Exhibition Center in 2010. He concedes that Tripoli needed (and still needs) new developments but adds that Niemeyer spent no more than three weeks in Lebanon before he designed it, and that it repeats the vocabulary of several of his other projects – the boomerang-shaped canopy, for example, was used in the University of Brasília. “I don’t want to demean the project – spatially it’s very interesting,” El Kadi says. “But the shapes were never married with specific programmes in mind.” The space museum is rumoured to have been used by the Syrian army, which occupied the site as a base for much of the civil war, to launch attacks; Niemeyer’s “revolutionary” housing complex was turned into a Quality Inn, the city’s only hotel (El Kadi quips that it should be called “Quality Out”). One of El Kadi’s Yale students programmed the fair as an art biennial and museum; another made it a national library that included contemporary religious studies. It has also been a university campus and a kibbutz combining living and agriculture. “I would definitely characterise it as a ruin,” El Kadi says. “One of the projects we were interested in was turning it into a zoo. Its dilapidated nature makes it no longer of any use for humans – the scale has more of a jungle feel. It’s a 21st-century ruin. How can we reuse it It’s not going to remain like this forever.” Joe Nasr, an urban planning scholar who was born in Beirut and now lives in Toronto, sees the project differently. He wrote his dissertation on ruins, and is currently working on a book about the fair, along with his colleagues George Arbid, Mousbah Rajab, and his wife, June Komisar. “One thing about Niemeyer’s projects is that they have strong structures. They are almost nothing but structure, which is why they can last for years with little care. The use of concrete and the designs themselves can withstand the passing of years or even decades, so in that sense, I wouldn’t call it a ruin. But what it does share with ruins is a lack of transformation, except for what has been affected by time.” Nasr adds that Niemeyer approached architecture as though it were sculpture. Because the fair was never implemented or used, it retained its sculpture essence – it’s basically Niemeyer’s work in its purest form.

Ramp and gateway arch leading to open – air theatre (image: Cristobal Palma) Nasr and Komisar managed to speak to Niemeyer and his assistant about the building. (The office of the 104-year old Niemeyer in São Paolo didn’t respond to my requests for comment.) “He has a fond appreciation of it,” Nasr says. The interview confirmed their sense that it is a project forgotten even by its designers, who didn’t realise the degree of its completion. “Some aspects are unfinished, but most of it is quite finished,” Nasr explains, “and it is among the larger projects by Niemeyer. But when we talked to Niemeyer or his assistant they both were treating it as something that was an interesting experience and then didn’t get done – a distant memory in a way.” The back-story to the fair’s neglect is not complicated. Although construction started in 1962, it was never planned for phased opening, and by the time it was finally ready to open in 1975, over a dozen years after its inception, the war broke out. “And then everything changed,” Nasr says. “It was occupied, then it was abandoned. It remained frozen in time.” Regardless of how the fair is now perceived – as a useless folly or a place of unfulfilled potential – it remains a poignant symbol of Lebanon’s aborted promise. But more than that, it is an example of Niemeyer’s modernist utopian optimism. In his acceptance speech for the 1988 Pritzker Prize for Architecture, Niemeyer said: “A concern for beauty, a zest for fantasy, and an ever-present element of surprise bear witness that today’s architecture is not a minor craft bound to straight-edge rules, but an architecture imbued with technology: light, creative and unfettered.” The strange appeal of Niemeyer’s Fair lies in no small part in its otherworldly aspect – even as the buildings slowly give way to the effects of entropy, they still possess the power to enchant, appearing like spaceships about to launch into the stratosphere and an unknown future.

Tepee-like structure – many of the forms had no specific programme (image: Cristobal Palma) |

Words Claire Barliant |

|

|

||

|

Auditorium, intended for use as an experimental theatre (image: Cristobal Palma) |

||