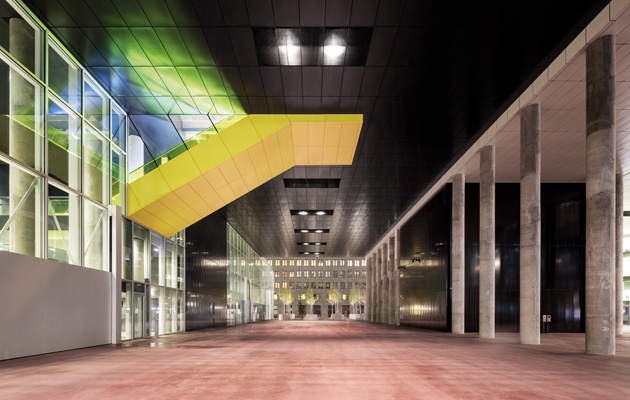

Rijnstraat, The Hague. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti

Rijnstraat, The Hague. Photo by Delfino Sisto Legnani and Marco Cappelletti

The OMA partner tells Matthew Ponsford about clubbing with her daughter and what sort of buildings she likes designing best

Ellen van Loon is a partner at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), where she has worked since 1998. She has led a string of internationally acclaimed political and cultural projects including Casa da Música in Porto (2005), winner of the 2007 RIBA European Award, and the Dutch Embassy in Berlin (2003), winner of the Mies van der Rohe Award in 2005.llen van Loon is a partner at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), where she has worked since 1998. She has led a string of internationally acclaimed political and cultural projects including Casa da Música in Porto (2005), winner of the 2007 RIBA European Award, and the Dutch Embassy in Berlin (2003), winner of the Mies van der Rohe Award in 2005.

Van Loon’s reputation for creatively interpreting major commissions has been cemented by the recently opened Danish Architecture Center, known as BLOX, in Copenhagen (2018) and Rijnstraat 8 (2017), a Dutch government building that creates an open and collaborative environment for three ministries. She is currently working on OMA’s first major commission in the UK, a multi-arts venue called The Factory that is set to become the home of the Manchester International Festival (MIF), and the renovation of the Dutch parliament in The Hague. Effusing excitement for this daunting slate of projects, van Loon discusses lessons learned while visiting nightclubs with her teenage daughter, how she gives audiences a view behind the curtain, and why she prefers some ‘irrational’ decisions to the macho architecture she observed while working with Norman Foster.

BLOX, Copenhagen. Photo by Richard John Seymour

BLOX, Copenhagen. Photo by Richard John Seymour

Icon: I read in The New York Times that you’ve been preparing for The Factory by going to raves with your daughter. How was it?

Ellen van Loon: I went to some clubs in Amsterdam – Melkweg and Paradiso – and some big outdoor festivals in Belgium and in Holland. Because the thing is, I’m not the youngest any more! And of course the Manchester project is also for young people. We’re talking kids of 16, 17.

Icon: What did you find out?

EvL: Actually, it’s not that different from when I was younger. The only difference is this whole DJ thing didn’t exist then. Also hip-hop culture didn’t exist. That culture is really nice, because it is a kind of quite direct communication with the public. And it’s almost like spoken word: it gives a very strong relationship between the public and the performers.

Icon: And how did your daughter feel about it?

EvL: That’s always a very difficult one! No, the funny thing is, I was the only older person. I think the age, generally, was probably from 18 to 25, so I was absolutely the oldest. She always feels a bit ashamed, but thinks it’s funny at the same time. Quite often we enter and she’s like, ‘Oh mum, I’ll see you later.’

Icon: For Manchester, how did you design with the knowledge that you’re creating for new forms of culture, which perhaps don’t exist yet?

EvL: Yeah, that’s very difficult. The Manchester project is all about changing the relationship between the performer and the audience. So, in the theatre, you can basically have the stage and the audience, or the audience can be on the stage, or vice versa. You can do whatever you want.The artistic director of MIF [John McGrath] told me a very nice story. He said, ‘I once organised a festival. And there was a container yard in the back and there were young kids, basically creating a performance, between the garbage containers.’ That was a big inspiration. I mean if you think about where hip-hop started, that was in the poorest neighbourhoods. It is about the young who create things, basically out of nothing, somewhere outside the museum. How can you include that? That’s why I was suggesting we should just keep the whole ground floor open, and give it to young kids for free, so that they can do their own things in the building.Maybe that is the core of what I realised most when I went out with my children. There is so much creativity embedded in every new generation that we should really make sure that we don’t miss out on it.

Icon: There are similarities with this across your cultural projects but also in political buildings like Rijnstraat 8 too. It’s quite easy to make an open, flexible space that’s boring, but how do you make one that’s enlivening?

EvL: I think one thing that we are almost obsessed with is making connections between stages, so that one stage can start [interacting] with another stage. We also do a lot of differences in level. So that a space can be a balcony to another space.

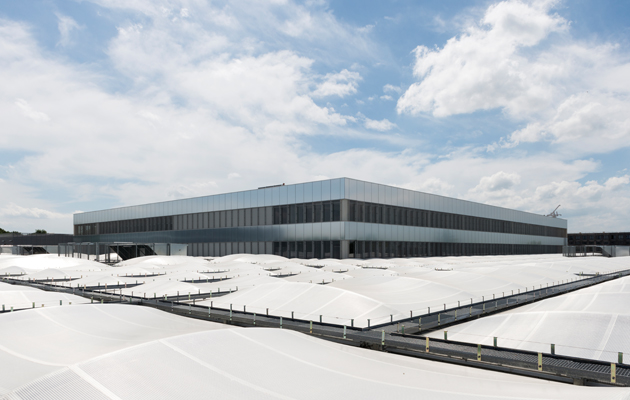

Lab City engineering school, Paris. Photo by Antoine Cardi

Lab City engineering school, Paris. Photo by Antoine Cardi

Icon: There’s also this continuing interest in making production space visible – in Manchester and at BLOX in Copenhagen – with viewers able to look through to the backstage and see what’s going on. Do audiences want that?

EvL: I mean, in hotels, there’s a whole world [behind the scenes] and in theatres it’s very extreme. Because performers spend more time backstage, not seen, than onstage. Maybe they need to rehearse for three months to make a performance that lasts two hours.I found this out because people love to come and see how we create architecture in our office: the models, the physical things. Casa da Música was the first time that we tried it. We put a lot of glass between the front-of-house spaces and the back-of-house spaces. So the public could see musicians rehearsing. In the beginning there was a total shock moment because the orchestra using the building is a classical orchestra, and classical orchestras are quite conservative. They called me after the building was finished, and were like, ‘I want curtains everywhere, because actually we don’t want to be seen.’And I thought, I’m just not going to answer that. I’m just going to wait for a year. And after a year I didn’t hear anything any more. They are seen when they rehearse and they don’t mind, because it’s also part of the attraction, the performance.

Icon: You’ve also mentioned your experience starting out working for Norman Foster, and not being a big fan of the Reichstag, and that kind of overwhelmingly masculine, unadaptable building.

EvL: I worked on it, so I know how masculine it is.

Icon: Are there government buildings that aren’t so rigid or macho?

EvL: Well, there could be. But be aware, the architectural profession is pretty male. And in Foster’s architecture, it is pretty stiff, you know? When I worked at Foster’s, everything was explainable. But our senses, what we feel, is not always explainable. So I do like buildings where the rational and the irrational choices are combined. Sometimes a journalist asks me, ‘Why is this pink?’ I’m like, ‘Well … I like it. It felt good, that’s why I did it.’ And Foster’s architecture is not like that. Everything is explainable.

Amsterdam HQ for G Star Raw

Amsterdam HQ for G Star Raw

Icon: One of the things that fascinated me about Rijnstraat 8 was the process of reuse, where about 99% of materials were recycled. How is that possible?

EvL: In Holland, recycling is business. So we have an enormous amount of factories recycling materials. Electrical cables are recycled. Carpet is 98% recycled. The only product where we’re still struggling with recycling is glass. Apparently when you recycle glass into new windows, it needs to be extremely clean, otherwise you get weak points and it just breaks. But of course, a lot of old glass is reused for making bottles, making glass bricks, etc.

Icon: Over the last decade you’ve completed a lot of major projects. Would you do a private home?

EvL: What I like most is working on theatres. Performance spaces are my favourite. However, any building with a specific function, I like to work on. I am now doing a courthouse in France. I have never done a courthouse before. It’s a whole different world, I have to find out how it all works. You have to think about how the detainee moves through the building, what the space is for the magistrate, etc.Any of that is interesting for me. And at the moment, I’m not doing any offices, nor any houses. So I’m really happy. I’m doing a school, I’m doing a theatre, I’m working on the Dutch parliament. And I’m doing a courthouse, and a museum. So it’s quite specific things.