|

|

||

|

One of the city’s few surviving warehouse districts is now a thriving design quarter, but is there a long-term future for this unlikely union between creatives and developers? Debika Ray reports Since 1979, when the Chinese government designated Shenzhen a special economic zone, it has grown from a cluster of villages to a megalopolis of more than 10 million people. With its single-party political system and unparalleled growth, China is uniquely positioned to carry out large-scale urban experiments that would be unthinkable elsewhere, as Doreen Heng Liu, founder of Chinese architecture practice Node, observes. “If it goes well,” she says, “it becomes state policy.” It’s certainly worth keeping an eye on another experiment that has been underway since the early 2000s: the effort to establish China’s reputation as a creative hub, challenging the perception that it’s a country where things get made but where creative exploration is discouraged. One of the most visible outcomes is the emergence of culturally oriented neighbourhoods in China’s major cities – spaces, from Beijing’s 798 art district (one of the earliest examples) to Shanghai’s M50, where young creatives can work, mingle and showcase their craft to the public.

Loft’s industrial buildings now house art galleries, music venues, eateries and offices for many graphic design studios In Shenzhen, this trend comes in the form of OCT Loft, a sprawling complex of former industrial buildings in the city’s Nanshan district named after the developer, Overseas Chinese Town. Over several years, it has been converted by celebrated Chinese architecture practice Urbanus into a mixed-use development populated by the city’s creative professionals and, in particular, graphic design studios. These have sprung up in response to the city’s booming business sector and the associated demand for branding and communications services. OCT Loft’s transformation kicked off in 2003 when the He Xiangning Arts Museum set up OCAT, a contemporary art gallery, in one of its warehouses. And, for several years, Shenzhen’s formidable biennale of urbanism and architecture (UABB) was also based at OCT Loft, cementing the area’s status in the global design consciousness. Today, the neighbourhood is an established hipster hangout, containing office space, apartments, design-led bars, a beloved bookshop/cafe called Old Heaven Books, popular music venue B10, several public and private galleries and a scattering of furniture, antique and fashion stores. Designers from Shenzhen and further afield sell their work at the fortnightly street markets and the popular annual OCT Jazz Festival attracts performers from around the world.

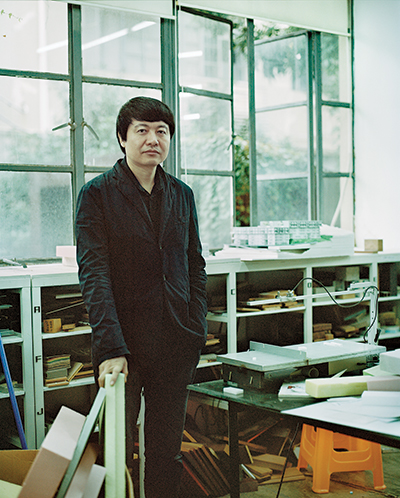

Michael Wang, above, is art director of 2m2 Design

The neighbourhood, with its low-lying buildings and pedestrianised streets, stands in sharp contrast to the megastructures that characterise the rest of the city. “The fabric of OCT doesn’t really fit the city fabric, which makes it unique,” Meng Yan, one of the founders of Urbanus, tells me when I visit his office. “The streets are meandering, and respond to the contours of the landscape.” Urbanus’s intervention took into consideration the lack of walkable public space in the wider city. “The biggest thing we did was create a pedestrian pass through the centre of the development, cutting through a factory and connecting a cluster of apartments to the rest of the neighbourhood. Then we gradually added little public spaces, galleries and connectors.” Crucial to attracting creative tenants was flexibility of design. “The whole thing develops gradually. People move in and if they want to renovate we give them minimal guidelines. We don’t limit them too much. It’s under control and at the same time not.” All of this fosters an atmosphere that creative businesses find attractive. “The environment has allowed close communications with our counterparts in the creative industry,” says Hei Yiyang, creative director of Sense Team, a graphic design practice that has been based in OCT Loft since 2014. “And the cultural and art events have had a positive effect on recruitment.”

With its comparative political independence and international connections, it is perhaps no surprise that, among China’s cities, Shenzhen is one of the most fertile for a creative community. In 2008, it was appointed a Unesco City of Design for the strength of its maker culture. It was, in fact, the city government that initiated the UABB in an effort to generate an open dialogue about the future of Chinese cities. “The Shenzhen government is exceptional – the city is only 30 years old, and compared to others the government is very open to new things and to the exchange of ideas,” says Liu. Hei agrees: “The Shenzhen government is willing to invest in creative and design industries. And with the development of creative industries, the social status of designers is gradually increasing.” But this laissez-faire attitude to creative development is countered by the more interventionist role taken by the site’s state-owned developers. “The developers are actually involved in the day-to-day management of OCT Loft, including the mix of tenants,” says Meng. “If we warn them, for example, that we have too many eateries, we figure out a way to attract more designers, to balance production and consumption. There is always a dialogue.” This is Hei’s experience, too: “Our relationship with OCT Loft is not limited to renting the office – we have a lot of cooperation with them; for example, we did the promo materials for its Jazz Festival.”

The area’s aesthetic and amenities attract young creatives

Curatorial assistant Guo Jiachen in Sense Team’s office, which is also home to seven cats When I visit OCT, the biennale of urbanism and architecture is again underway – this time in the city’s Shekou port district. Fittingly, the theme this year is “reliving the city” – a call for participants to explore how a city’s existing fabric can be repurposed for today’s needs, rather than simply building new structures. To create a venue for the event, Liu – one of the curators – renovated a former flour factory, no doubt hoping that it might attract some of the success OCT Loft has seen since the biennale began there. But Liu echoes Meng’s suggestion that the long-term fate of such developments is tied to the attitude of its developer. “The OCT developer used the biennale platform very well to create a win-win situation – both art and business succeeded.” However, the owner of the Daucheng flour factory, China Merchants (another state-owned developer), has already mooted knocking down the site’s main building to make room for a road, somewhat contradicting the central thesis of the event it’s hosting. “That’s why I’m not quite so positive about the future of this place, even though I’ll really fight for its survival,” says Liu.

Urbanus founder and architect Meng Yan in his office

The main building of the 2015 Shenzhen Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture Then there is the question of what exactly “success” means when it comes to a creative neighbourhood – it can’t be ignored that there is a huge economic value in culture and this often leads to the core creative residents of such areas being priced out. It is a move that has already happened in Beijing, according to Beatrice Leanza, the director of Beijing Design Week. “798 is massively visited but over the years its internal creative ecosystem has been wounded. The mix of offerings has become deregulated, heavily relying on retail ventures. The result is that the few galleries left sit amid myriad small shops and cafes that bring little aesthetic value or consistency to its history … Sure, many of the big commercial players of the local art scene are still there, and the foot traffic is like nowhere else, but after 7pm, when the ‘shoppers’ are all gone, the area turns into a graveyard. The governmental agency that manages 798 has definitely made a good business of it, but after more than 10 years, the experiment needs re-envisioning.” While OCT Loft’s high concentration of creative businesses, rather than artists, may help to shield the area from this phenomenon, it is still vulnerable to the forces that have made 798 unaffordable for young creatives. “We’ve started to see more fashion stores, more cafes and other entertainment. When we moved in there was only one restaurant and everybody ate there, but now there are hundreds – and the danger is that the designers might later be gone,” says Meng.

Old factory buildings and Chinese contemporary sculpture in Beijing’s 798 art zone |

Words Debika Ray

Photography Catherine Hyland

Above: We don’t limit tenants too much. It’s under control and at the same time not |

|

|

||