|

|

||

|

Protest camps are constructed rapidly, using everyday materials as objects of disobedient design. But the hasty architectural decisions made by protesters can come to symbolise their movement and deepen its impact From the cunningly planned to the irreverently accidental, there is a chaotic mobility about the architectures that make up protest camps. Their design dynamics are promiscuous – ideas travel across time and place, between cities, countrysides and continents. The limited resources and heightened emotional settings of the camps alter the stakes of design, resulting in the creation of ad hoc architectures. In urban locations, protest camps such as those in Hong Kong and Istanbul’s Gezi Park manifest what the architect and curator Adam Bobbette refers to as “counter-cities within the city”. In just a brief time, they can produce “a world of self-built, rapidly organised and often beautiful tools of protest, leisure, worship and infrastructures.” The act of building a public place for protest and dialogue has long had a place among the tactics of resistance movements. Protest camps are distinct from other forms of social movement, such as demonstrations or marches, in that they are living spaces, and they make visible all of the architectures and objects required for the social reproduction of protest and daily life, from kitchens and showers to media centres. These structures, objects and environments are a critical part of what makes social movements work the way they do. While colourful tents act as set design on the hyper-mediated stage of protest, and are often perceived in this light, there is a tactical element to this artful display. The spectacular aesthetics of protest camps exploit the symbolic potential of textiles and building materials – these are everyday, functional objects transformed into powerful acts of defiance. Architect Gregory Cowan, who studies the role of protest in the built environment, sees the appearance of tents in occupations as “a choice of architectural strategy that is not merely pragmatic. Ideological reasons underpin the uses of these kinds of structure.” For Cowan, the tent’s indeterminate, mobile, temporary and rapidly deployable qualities make it both theoretically and architecturally important as a counterpoint to the idea of home as static and nuclear, and to buildings as solid and stately. |

Words Anna Feigenbaum

Above: A makeshift shrine-cum-barricade in Mong Kok, Hong Kong

Images: Herkes Için Mimarlık (Architecture for All); Lam Siu Wing (SWING)/Martin Witness (facebook.com/martinwitness) |

|

|

||

|

Tents being dismantled in Admiralty |

||

|

One of the earliest and greatest feats in defiant architecture came with Martin Luther King Jr’s plans to bring thousands of poor people to the US government’s door to demand change. Under a sloganeering mandate to create a “city within a city”, Resurrection City in Washington DC was a protest camp on a scale never before attempted, surviving for six weeks in 1968 before its eviction. Professional architects and urban planners modelled this 15-acre encampment loosely on army camps and sites for migratory workers. The parkland was divided into a series of subsections or “community units” using a grid system. Dozens of volunteers helped set up and run a dental centre, healthcare centre and kitchens serving three meals a day, alongside the Many Races Soul Center, the Poor People’s University and the Coretta Scott King Day Care Center. Yet while there was much to celebrate in this city within a city, there were also challenges: a problem laying sewage lines, heavy rainfall that produced muddy conditions and blocks that, rather than facilitating inter-racial mixing, became segregated. In contrast, a new type of transnational protest camp emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s to solve the “housing crisis” that campaigners faced during various protests at summits and social forums. By 2003, the third Intercontinental Youth Camp, at the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil, had grown into a ten-day affair, bringing 23,500 people together from across the world in a makeshift city, complete with its own currency, made up of self-managed neighbourhoods, including an eco-built media centre and cultural and workshop spaces. |

||

|

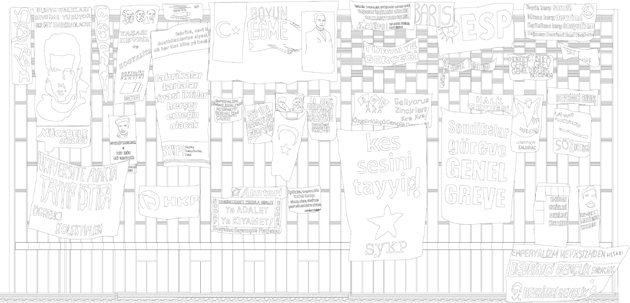

Illustration by Architecture for All of banners hanging from the Atatürk Cultural Center in Taksim Square, Istanbul |

||

|

A circular “barrio”-style campsite served to both facilitate and symbolise this consensus-based, non-hierarchical structure. Recent occupations in places such as Gezi Park and Hong Kong did not benefit from the rigorous pre-planning or large open spaces of Resurrection City and the youth camps, thus were more heavily shaped by the limits and possibilities of existing built and natural environments. “Hong Kong’s hyper-dense, commercial architecture both exacerbated and facilitated the protest movement,” explains Bobette. As writer and photographer Christopher DeWolf suggests, Hong Kong is “a city that lacks a large amount of quality public space”, thus, instead of gathering in squares or parks, activists “made their own space, turning highways into places where people can gather”. The main protest site was located on a tight junction in Admiralty, trapped between towering shopping malls and oversized government offices. The tents were arranged in rows, fitted neatly between the highway partitions, which themselves had been repurposed as community noticeboards, their concrete expanses acting as canvases for political expression. Demonstrating once again that police crackdowns on non-violent demonstrations will rally people to a cause, the tear-gassing and baton beatings of September last year brought thousands out onto the streets. As the popularity of the student-led pro-democracy movement grew, the main camp in Admiralty expanded, with new supporters and supplies pouring in. For the next two months, campers established a self-sustaining counter-city that housed ad hoc libraries, classrooms, food supply stations, a cinema, allotments, art exhibitions and even wood and umbrella workshops, creating objects that were at once both practical and beautiful.

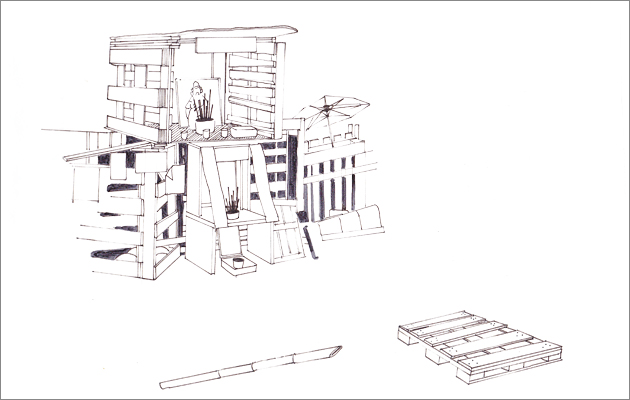

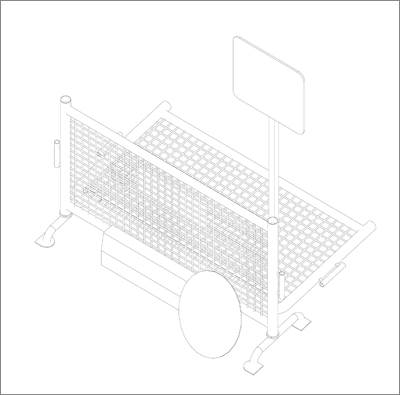

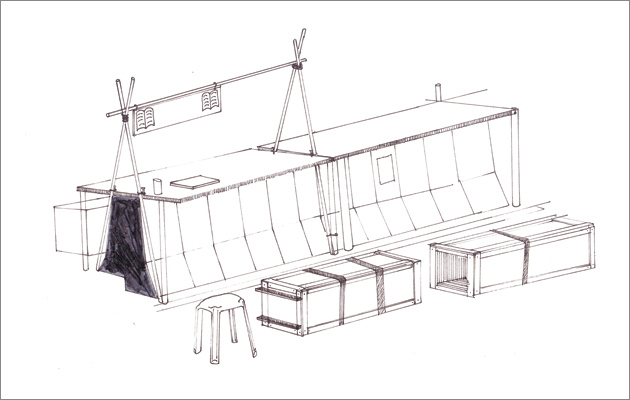

An axonometric of a Speakers’ Point by Architecture for All Illustrator Lam Siu Wing’s sketches of these hastily constructed architectures capture the ways that objects at protest camps are always entangled with people to make politics possible. In this moment of in situ design, materials were rearranged by people to care for others – scaffold poles met storage crates to form pop-up dining tables, staircases were constructed over road dividers, while the space of the highway was occupied as a people’s kitchen, a place to feed the masses and refuel the movement. At the same time, Lam’s drawings create instructional documents, open-sourcing architectural elements. As design specifications, they teach others how to repurpose everyday materials into objects of affinity and counter-repression, becoming practices of disobedient design. They contribute to the promiscuity of protest-camp architectures as they are blogged, tweeted and reposted around the world. The yellow umbrellas that came to symbolise Occupy Hong Kong demonstrate this process. At first, umbrellas were used to create an extendable textile barrier between protest and police lines, but they evolved to become a central decorative and structural feature of the movement’s three camps. Used as canvases, they bore the messages of the movement, but were also propped into metal barricades, affixed to shelters as ceiling extensions and secured to street furniture to shield the plants in newly created urban farms from the sun. |

||

|

Illustration by Lam Siu Wing of the shrine-cum-barricade, Mong Kok, Hong Kong |

||

|

Just over a year before Occupy Hong Kong, in the summer of 2013, protesters in Istanbul set up camp in Gezi Park to protest against the proposed construction of a shopping mall, barracks and luxury flats over one of the few remaining green spaces in the city. By camping on site, protestors physically prevented, if only temporarily, the destruction of the park. This use of the camp as a barricade makes Gezi similar to other blockade-style camps set up to protest against house evictions, weapons manufacturing, logging companies or, increasingly, fracking sites and oil-pipeline construction. The architecture of blockade protest camps such as Occupy Gezi is erected in direct opposition to the architecture of its surroundings. By the occupation of such sites, the human-object entanglements of camping are deployed as a means of sabotage and disruption. Yet the camps that people build together do not merely act as barriers in the pursuit of a goal; they develop infrastructures and practices in an attempt to put their ideals into practice. In the face of excessive – and sometimes lethal – police force, Gezi protesters still managed to create a makeshift mosque, a mobile food centre and a flower garden, among many other architectural features and facilities. Herkes İçin Mimarlık (Architecture for All) has been sketching photographs to memorialise the unique structures created amid the protest camp. “While we were in the park, we tried to photograph what we thought could be interesting, and we created a pool for photos from Facebook and Twitter – we were particularly interested in the use of the scrap materials, and the in situ design solutions,” the project’s editor and coordinator Yelta Köm explains, highlighting some of the key features that shaped the architectures of Occupy Gezi – its variable grassy and concrete landscape, the hot summer climate, and the violence that protestors faced from Istanbul’s police force.

An axonometric of a Speakers’ Point by Architecture for All As political occupations, protest camps enact a collective refusal to leave that interferes with and takes back the city. They confront capitalism’s landscapes – its super-highways, shopping malls, commercial centres and privatised squares – and re-create them as places that are both more human and humane. In redirecting the rhythm and flow of urban movement, these occupations become desire paths, replacing the enforced paths of our normal lives, introducing a new intensity to interactions. In contrast to the architectures of our atomised cities, of the commuting and commercial routines that dominate our existence, they offer structures that facilitate human connection. Yet it is important not to overly romanticise protest camps. Köm reflects that Occupy Gezi was both a common ground and “a conflict space”. At protest camps, people must live and work together 24/7. While they may share a common cause, protest campers’ ideas, experiences and ideologies can both converge and clash. Heightening these tensions, protest camps are vulnerable spaces where people are constantly exposed to the police, the media and the elements, and to the clicks of tourists’ cameras. Embracing the spontaneity of protest camps can lead architecture in new directions. “No one can design an urban-based protest camp in conventional ways,” says Köm. “The key design challenges will always be different in every individual situation.” Examining how people respond to these challenges can ensure that imaginative architectures do not remain as conceptual designs only, but can be realised in practice, built on occupied streets, parks and squares around the world. Anna Feigenbaum is the author of Protest Camps. This article first appeared in Icon 141: Camps, under the headline “Occupy architecture”. Buy back issues or subscribe to the magazine for more like this |

||

|

Illustration by Lam Siu Wing of desk-cum-road barrier in Admiralty, Hong Kong |

||