|

The building sits next to UN Studio’s Erasmus bridge (Image: Ossip van Duivenbode/OMA) |

||

|

Rotterdam is not a pretty city. Almost completely flattened during the Second World War, it was rebuilt in a no-nonsense post-war style, with a centre made up mostly of dreary office blocks. Dominated by its port, one of the world’s largest, Rotterdam has long struggled with under-occupied and low-value commercial space. But this profusion of cheap offices has been handy for architects, who have been able to set up without worrying too much about overheads – none more prominently than OMA, whose enigmatically nondescript office we visited in Icon 100. But if this is the character of Rotterdam, then De Rotterdam is a little odd. Well over 150m tall, and occupying a prominent site on the Wilhelmina Pier, it’s a 120,000sq m mixed-use scheme comprising three glassy towers that contain flats, a hotel and office space, plugged into a large plinth. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it is – De Rotterdam is another example of what we now expect from developer-led construction. But in a city awash with space for rent, still in the doldrums of the financial crisis, it seems strange to be adding 60,000sq m of office space.

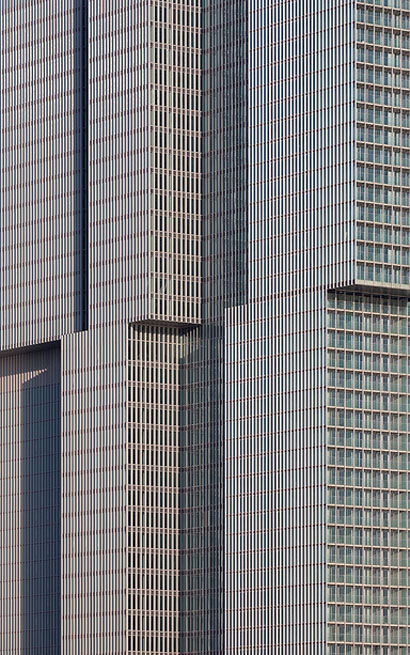

“The first crisis nearly killed the project; the next crisis revived it,” OMA founder Rem Koolhaas says. The scheme first emerged in the late 1990s, but vanished after the 11 September attacks in New York; years later, the turmoil and cheaper construction costs of the global recession gave the developers the scent of an opportunity to proceed. The initial design was typical of OMA’s then-obsession with thuggish juxtapositions (as exemplified by its Hyperbuilding project of 1996), and comprised a number of staggered boxes with varying fenestration, complete with diagonal elevators drifting across the facade. The building as constructed is much more sober, with three towers, each divided into two chunks by cantilevers and draped in vertically accentuated facade panelling – a continuation of OMA’s recent habit of paying ironic homage to Yamazaki’s World Trade Center. From most angles, the towers merge to form a rugged slab, but the approach from UN Studio’s Erasmus bridge reveals the canyons and voids between them. “It’s interesting for me that a building can have two identities,” Koolhaas says. “It enriches every part of the city in a new way.” There’s not much to say about the inside. The generous lobbies are a cut above the corporate norm, but the upper floors are conventional. It is a testament to OMA’s successful turn towards commercial architecture that this is a far more interesting building than it would have been if designed by, say, Foster + Partners, but it is still difficult to be enthused by yet another luxury “vertical city” that gives little back to its surroundings.

|

Words Douglas Murphy |

|

|

||