|

|

||

|

Xintiandi, home to a two-week design festival at this year’s Design Shanghai, laid the ground for a new wave of developments that mix retail, cafes and public space Since Rem Koolhaas’s Junkspace introduced malls to the academic canon, there’s been an entertaining race to publish the definitive survey-cum-autopsy. The latest is World of Malls from Munich’s Pinakothek der Moderne, interspersing case studies with essays brooding over the decline of the street. It tells a largely Occidental tale, with occasional excursions further afield. China is all but absent, despite boasting three times as many malls as the United States. The presumption is that the former offers little beyond generic cases of ill-considered, inward-looking megaprojects struggling with occupancy, destroying heritage, and presenting little but hostility to their surroundings. Western reports focus on high-profile Chinese examples as an excuse to deride their architecture as nostalgic, futuristic or naive. And there are certainly problems. It is expected that a third of malls will be bankrupt by 2020. The New South China Mall in Dongguan, a third-tier city, claims to be the world’s largest at 660,000sq m, but has long failed to attract outlets and visitors. Even seductive examples such as Zaha Hadid Architects’ Galaxy Soho in central Beijing, criticised for destruction of vernacular architecture, have encountered unexpectedly high vacancy rates. The bursting of this particular bubble, inflated by the Chinese economic boom, is not unexpected, particularly given the rise of internet retail. Yet, quietly, a sophisticated alternative has gained traction. Its roots can be traced back to the Xintiandi project, developed by Shui On Land in Shanghai’s historic French Concession. Originally a neoclassical SOM project wiping away 90 per cent of the late 19th-century shinkumen housing, it was eventually handed to Benjamin Wood instead, fresh from renovating Michael Lapidus’s Lincoln Road in Miami. His more considered style struck a 50/50 balance between conservation and rebuilding, preserving its ‘spatial framework’ of car-free main and cross lanes, with a couple of contemporary structures thrown in.

Taikoo Li Chengdu, developed by Swire Properties with Oval Partnership (2009– ) Greeted with scepticism and ambivalence upon its 2001 opening by authorities, who felt outside space would not attract audiences, and overcoming an initial reputation as an expat oasis, it has been an unprecedented success, with design stores and boutiques flourishing alongside a cafe culture. Coinciding with the rise of China’s middle classes, and possessing a cultural context that has a particular, unique romance for Shanghai, the impact has been little short of revolutionary, symbolising a new equality in China. As Wood puts it, ‘When I started out, there were a couple of million people considered middle class in the whole country, now there are 350 million. Prior to Xintiandi, if you went to any major city the only public spaces were big plazas where the military had parades three or four times a year, or huge restaurants with harsh lighting and acoustics. Xintiandi was something that the people of Shanghai needed desperately, but didn’t know it.’ Since then, ‘to Xintiandi’ has become a verb, even a cliché, describing the transformation of an urban area, ideally with heritage elements, into a lucrative, open public and commercial space. Direct copies now exist across China, encouraged by local governments, but with imposed grids that suggest the prioritisation of style over substance. Another side-effect has been a new awareness of the commercial value of Chinese culture, and vigilance around its protection or restoration, in contrast to the wholesale rebuilding of such neighbourhoods 30 years earlier. Xintiandi itself was never a preservation project. Buildings were demolished and doorways and windows added or enlarged to maximise retail. As Wood says, speaking of the troubled genesis of his huge project at Lingnan Tiandi in Fo Shan: ‘Unless a place is commercially successful, it will not withstand the test of time – you’re not going to keep pumping money in if there’s no one to pay rent. You have to treat preservation as an evolving phenomena, and part of evolution is that buildings are allowed to change – not wholesale destruction, but change is part of life.’

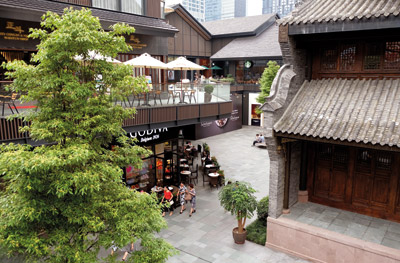

Xintiandi, Shanghai, developed by Shui On Land with Benjamin Wood and Carlos Zapata (1998–2001) Liberties are harder to take today, for better or worse. Authorities prefer a meticulous ‘recreation’ of facades, despite a lack of documentation and an often ruthless approach to surrounding streets. The controversial redevelopment of Qianmen, just south of Tiananmen Square, prior to the Beijing Olympics, epitomises this official pursuit of a highly consumable version of cultural heritage. Wood’s practice, Studio Shanghai, is not alone in developing strategies for external space. Hong Kong’s Oval Partnership has been involved with two of the most high-profile, Taikoo Li Sanlitun, Beijing (designed with Kengo Kuma), and Taikoo Li Chengdu. Both ungated, low-density, pedestrianised developments by Swire Properties, with infrastructural elements underground, the former is contemporary, consisting of 19 buildings with faceted facades by a variety of architects, but with an open, informal layout suggestive of traditional alleys and courtyards. The project is highly unusual in polluted, pedestrian-hostile Beijing, but has been a significant success, often cited as the capital’s top mall. Chengdu’s version includes six heritage buildings around the Daci Temple complex, and reflects this architecture in two-storey, pitched-roof pavilions and a pattern of fast and slow lanes and raised walkways. Again, in a city notorious for its excess of malls, the approach has been effective – almost too much so, as brands oust dining, undermining its viability as a social space.

Lignan Tiandi in Fo Shan, developed by Shui On Land with Studio Shanghai (2003–09) To some degree, the Taikoo Li projects are shopping malls with roofs removed. Floor-to-ceiling heights meet luxury retail requirements, thus balconies and walkways have little relationship to the ground. And to characterise Chengdu as a heritage project would be naive – individual structures are well preserved but inquiring as to what previously surrounded them is futile. Yet porosity is undoubtedly an asset. As Oval’s founding director Chris Law explains, ‘Projects like Taikoo Li provide rare civic spaces in city centres that everyone can use, so are a much-needed amenity, assisting the city government in creating a place that is pluralistic, richer, more diverse. While the developer provides high-rent and midmarket stores, this allows the opportunity for local people to do fly-by-night markets or satay stalls. I think on balance there is a positive effect on the way people live, helping to galvanise a sense of local identity … And developers are beginning to understand you can’t have a city that is just full of artisanal coffee, so they’re also starting to provide spaces for start-ups or co-working.’ The above-mentioned developments cater to first-tier cities with populations in tens of millions, but should be taken seriously as indicators of future directions. Permeable, low-lying and low-density environments of pavilions – easier to renovate than enclosed equivalents – can be viable, even in expensive central locations with varied climates, and make a real contribution to urban life, despite monofunctional and exclusive biases. One megacity remains firmly resistant. Hong Kong possesses the most famous concentration of malls anywhere, aided by mainland tourists and subtropical climate. This has been driven in large part by a prolonged private and public push in favour of a ‘city without ground’, deserting great chunks of streetscape for tunnels and walkways, many connecting one retail centre with another. This abandonment of public space, beyond diminutive 1970s ‘sitting-out areas’, leaves malls to fill the gap, usually integrated with, or even intrinsic to, multilayered transport and urban infrastructure, eliciting decades of hyperbolic megastructural rhapsodies from Western academics. Each mall tailors its air-conditioned atrium (and its chosen scent) to specific audiences, from the stylish, multistoried K11 Art Mall, to the linear luxury of Pacific Place, overhauled by Thomas Heatherwick in 2010.

Star Street in Wan Chai, developed by Swire Properties with Oval Partnership (2009– ) Yet even in Hong Kong a new approach is gaining ground. Swire chose to expand Pacific Place not by swelling outwards but by buying leases in a nearby cluster of sloping back streets, then turning to Oval to oversee the development of ‘Starstreet’, initially with a pop-up store and community consultations, then with investment in public spaces, staircases, signage and lighting, and with farmers’ markets and fashion events initiated through social media. The retail offer is tweaked, with a greater weight of hip, pricey bars and retailers. In fringe areas of Hong Kong, what seems at first sight to be gentrification – entrepreneurial hipsters occupying heritage structures in Sai Ying Pun or Wan Chai – is often contrived by savvy property companies. Among Koolhaas’s mercurial definitions of Junkspace was, ‘always interior, so extensive that you rarely perceive the limits’. China’s new breed of malls may have ventured outside, but it would be hard to deny that this description remains strangely apt. These spaces fluctuate between public and private, between high tech and heritage, between social exclusion and embrace, providing curated experiences that extract, with impressive precision, elements of both risk and reward from urban life. They bolster the pervasive role of consumption in our urban existence. Yet, in breaking down our stubborn adherence to absolutes when dealing with notions of street and mall, they offer something in return. Too many recent European efforts to insert malls within medieval street patterns have retained a focus on aggressively enclosed, artificial spaces, from David Chipperfield’s luxurious efforts at Innsbruck and Bolzano to any number of mediocre examples in Britain’s county towns. These are still felt to be the sole commercially viable manner of attracting investors and retailers – planners have yet to learn that their biggest asset could be the street itself. |

Words John Jervis

Above: Lignan Tiandi in Fo Shan, developed by Shui On Land with Studio Shanghai (2003–09) |

|

|

||