|

|

||

|

From our cities to our homes, OMA partner Reinier de Graaf considers the increasing irrelevance of humans in the continual and independent interaction between objects In February 2015, the New York Toy Fair featured “Hello Barbie”, a prototype for the first conversation-ready Barbie doll. Fitted with a microchip, Barbie had become the world’s first smart doll, complete with wireless connection and speech recognition technology. Sales pitch: “You talk, she answers.” The iconic girls’ toy, first launched in 1959, had been given her first real 21st-century upgrade. Able to play interactive games, tell jokes, adapt to personal preferences and “learn continuously”, the doll is designed to develop a unique relationship with her owner: “Smart Barbie will remember all of your likes and dislikes, you will become the best of friends…” Barbie’s incarnation as a smart doll, even if somewhat comical in its presentation, is symptomatic of the digital revolution’s increasing impact on our lives. Notwithstanding the privacy dispute that surrounded the Barbie launch, Cisco – one of the largest tech companies in the world – anticipates that by 2020 up to 50 billion objects will be connected to the internet: from children’s toys to remote-controlled cars, from advanced medical equipment to basic home appliances, on to hobby accessories, clothing and even pet collars. Equipped with sensors, transmitters and receivers, these objects will be able to gather and act on information ranging from your body temperature to your bank balance, from your eating behaviour to your breathing rhythm, from your sleeping pattern to your sex life, from your refrigerator’s content to your current relationship status, from your choice of coffee to its corresponding hipster level. Things have come a long way. When in 1982, a soft drinks vending machine at Carnegie Mellon University was the first device to be connected to a computer network, it was able to report on the amount and temperature of its contents. Today, thanks to the miniaturisation of microprocessors, the prevalence of wireless networks and the extension of battery life, the modest vending machine treats us to a hot or cold drink depending on the weather, is aware of our favourite snacks, provides vital information about allergens, alarms employees when bored teenagers sabotage the supply system, and never runs out of stock.

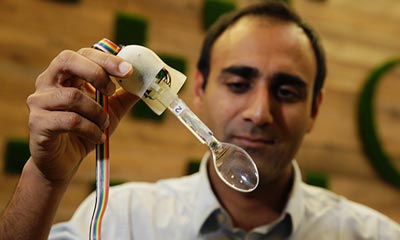

Google’s Smart Spoon steadies itself in a shaking hand Connected devices have come to anticipate and cater to our every need. It is no surprise that we turn to them even – or especially – in our most private circumstances: the convenience of our home. By far the largest market for smart devices conceived for our “comfort” is in the “streamlining” of our domestic existence. Nest, a Google – now Alphabet – owned tech-company, markets the Learning Thermostat, which also allows users to remotely control the temperature in their homes from their smartphones. The thermostat learns to anticipate their patterns over long periods of time, so it can eventually regulate the temperature on its owners’ behalf. Future-Shape, a German company pursuing large-area contactless sensor systems, has developed a textile floor surface with 32 sensors per square metre, which tracks movement to switch on the lights and open doors for us. TOTO, a Japanese manufacturer specialised in bathroom technology, has launched the Intelligence Toilet II featuring a urine “sample catcher” that measures glucose, urine temperature and hormone levels, using the data to wirelessly transmit a health report to your computer. Samsung has revealed a transparent touchscreen at the International Consumer Electronics Show to replace window glass, which they claim will be available within 10 years. The amount of smart technologies that can be integrated into our home seems endless. In 2015, British Gas announced a range of “smart home” products geared at the British market, designed by industrial designer Yves Behar. Behar said: “In the future, everything will be smart, connected and make my life easier in some way. More importantly, the technology is invisible – I never have to pull out my phone, hide my face in a screen even push a button, for the product to work. I think this is the shape of things to come: invisible design, where things magically happen around me…” The magic predicted to happen in the limited context of our homes is nothing compared to the digital magic announced on a grander scale by the so-called “smart city initiatives”. Around the world, cities from Amsterdam to Melbourne are eager to connect their infrastructure to the internet, hoping to improve their citizens’ lives, while streamlining ever shrinking public expenditures. Singapore is intent on becoming the world’s first “Smart Nation”. Given its compact size and highly educated population (90% of whom are in possession of a smart phone), that goal doesn’t seem unrealistic. In the imagined smart-city-state, traffic jams will be a thing of the past. The monitoring of traffic flows will re-route approaching, autonomous vehicles from the blockages; careful study of the weather patterns will anticipate and warn the populace of an upcoming heatwave or rain, and dispatch emergency service ahead of time to danger-prone areas. In a last instance, the automation of bureaucratic processes will rid the government of all unnecessary administrative work, possibly even of the need for governance itself… The interesting, or alarming thing (depending on how you look at it) in all of these developments is the displacement of the notion of control. In each case – the thermostat, the toilet, the floor, the window, and on a larger scale also the traffic and weather sensors in our smart cities – the devices are designed to both react to and trigger changes in circumstances. In doing that, these devices introduce a fundamental ambiguity of who is in charge. They analyse our behaviour over a longer period of time, which they then transform into an automated pattern that regulates the world around us, until eventually this world, continuously doctored and perfected, fits us like a glove. The patterns we leave, however incidental or random, become automated, eternal. They are our new truths. (Is it a coincidence that there is an acute resemblance between smart city marketing speak and biblical language?) The more our patterns are engrained, the more they become a straightjacket. Our unique identity, our behavioural DNA, becomes a form of solitary confinement, from which there is no escape. Thus far, the exchange of data in the smart architecture realm is primarily between humans and their objects. Various “smart” utensils collect information on our behaviour and relay that information back to us so that we can monitor and potentially modify our behaviour. In the near future however, that pivotal position of humans in the exchange of information is by no means a given. The theoretical incorporation of all devices, institutional as well as private, into an “Internet of Everything”, will also increase the exchange of data among objects themselves. Through ever more sophisticated artificial intelligence, the various artefacts in our lives will interact with their environment and one another in an increasingly autonomous manner. Objects will directly transmit information to other objects, without the intercession of humans. Our devices will independently act on whatever information is available at any given moment.

TOTO’s Intelligence Toilet II features a urine “sample catcher” that wirelessly transmits a health report to your computer Image the following scenario: You and your family have gone away for the weekend. Your house is empty, the doors are locked. You have let the neighbours know, but ever since the neighbourhood-wide introduction of a smart surveillance system, the old neighbourly task of ‘keeping an eye open’ has become outsourced. Prior to your departure, a urine sample has been taken by your smart toilet (part of a daily routine of smart health check-ups). It indicates you have a cold. In your absence, the information is relayed to your smart thermostat, which proceeds to raise the temperature in your home to the point where your smart windows decide to open themselves. This is caught on one of the neighbourhood smart surveillance cameras, which, apart from spotting suspicious behaviour, are also programmed to pick up on the more reassuring signs of occupancy, such as the opening of windows from inside. The camera’s observations (all good) are transmitted to the computers of the local police; because you are evidently home, your house is no longer a priority for police attention, and patrol patterns are adjusted accordingly. Police computers also feed the info on your supposed whereabouts back into the intelligent security system in your home: a courtesy service to the public, in case one forgets to deactivate the system, but also to prevent police response to false alarms. The smart alarm system is informed that you’re home, and goes into standby mode. Meanwhile, through the injection of malware into the police IT system, a band of burglars have gained access to real time information on the adjusted police patrols. Your smart home is now fair game for a break in. The open windows provide the burglars easy access. The touch screen facility fitted on the inside of the glass allows them to further deactivate the house’s internal security system (inasmuch as the all-safe signal from the police computers hasn’t done this already). Their footsteps, traced by the sensor-packed floors, help open whatever doors have remained closed inside. As an unexpected side note – at times, smart technology even takes its criminal users by surprise – the clear deviation from the usual pattern of footsteps is reported as a medical emergency to the computers of the local ambulance service, who arrive on the scene within five minutes. Fully in accordance with protocol, they escort one of the burglars to the local hospital where he is treated for injuries sustained from a previous break in. The same malware that has allowed the burglars access to police communication, has also provided them with your personal details: your CPR number, your bank details, your tax record and your medical history. In the hospital, staff are under assumption they are dealing with the home owner. Treatment is fully covered by and billed to your medical insurance. Upon your return you find a looted house. A substantial part of your of possessions is missing. All rooms in the house, including the ones of your kids have been paid a visit. There seems little pattern in what has taken the thieves’ fancy. Toys have been taken, but even in that there is no consistency. Smart Barbie has been abducted while Ken has been left. In what soon turns out to have been a critical mistake on the part of the thieves, a surreal spectacle ensues. Ken becomes the primary witness to the crime. Since the arrival of the Internet of Things, the latest iterations of interactive Barbie dolls are fitted with a device that allows them to telepathically communicate with their male counterparts. (The ups and downs of the love affair that inevitably unfolds between the two is designed to take their child-owner by surprise, adding an additional element of fun.) Ken has stored a record of Barbie’s thoughts during her abduction, from which her whereabouts can be deducted. His testimony proves vital. An extensive manhunt follows, and the thieves are eventually caught. While the perpetrators of the crime are being taken into custody, a team of attorneys works out the legal status of evidence provided by a doll.

A smart operating room The rise of smart devices, and the vast amounts of data which are being gathered and processed from individuals, have already raised concerns. America’s National Security Agency (NSA) and UK’s Government Communication Headquarters (GCHQ), among many other national governmental bodies and agencies, were embroiled in a mass surveillance scandal, revealed to the world in 2013 by Edward Snowden. Over many years, data was gathered globally and indiscriminately under the guise of national security. Smart buildings, and smart devices embedded in their elements, could provide an endless stream of data for governments and corporations to continuously access, effectively monitoring the minutest aspects of people’s lives, and over time learning about each individual’s habits. In 2013, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur Tom Coates connected his home’s smart devices to Twitter. House of Coates reports its everyday activities: “Someone just activated the Sitting Room Sensor so I’m pretty sure someone’s at home” and “Looks like Tom’s gone out. I saw him check in at Four Barrel Coffee.” If the house is turning into an automated, responsive cell, the city is increasingly a comprehensive surveillance system. Smart devices need not be under a malicious cyber-attack, but could be quietly mined for information either by corporate or governmental interests using built-in “back doors”. For instance, European lawmakers have already considered requiring all cars in their market to include a mechanism that would allow the police to stop it at any given time. In 2014, Jim Farley, a senior executive at Ford said: “We know everyone who breaks the law, we know when you’re doing it. We have GPS in your car, so we know what you’re doing. By the way, we don’t supply that data to anyone.” Extrapolating these developments onto the built environment, the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas said in the same year: “Soon, your house could betray you.” But even with back doors supposedly secured, potential hacking of the connected built environment poses a major security threat. Today, when the average person’s personal computer is infected with malware, the worst possible outcome is a loss of money and dignity. In the future and on an individual level, implanted medical devices could be caused to malfunction, and smart buildings, for all their intelligence, could become the targets of sabotage. In early 2014, a University of Michigan researcher was able to gain control over the signal colours of nearly 100 wirelessly networked traffic lights. As early as 2011, security researcher Jay Radcliffe has demonstrated that an automatic insulin pump used by diabetics could be hacked and its function ceased. The Economist magazine raised a similar concern for our dwellings in 2014: what if boilers could be hacked and made to explode? As security expert Joshua Corman said, “If my PC is hit by a cyber-attack, it is a nuisance; if my car is attacked; it could kill me.” The same could be said of buildings. In the 1970s Peter Eisenman designed a series of houses as a demonstration of the autonomous logic of (architectural) form over function – of the inescapable apartness between man and object. Architecture was to be liberated from the anthropocentrism that dominates it. Function, considered by many to be the primary cause of architecture, is only accessory to its deeper cause, the manifestation of meaning, of the idea. At the time, Eisenman provocatively referred to the inhabitants of his house as “intruders” to emphasise the feeling of estrangement that ensued from architecture’s autonomy. In the smart house, it is not so much the separation between form and function – between man and object – but the separation between man and function, which comes into play. The object is equated to its function in the extreme and automated to the point where a new alienation ensues in the form of a separation of man and the functioning of his home, even when that functioning is tailored to his own behavioural pattern. As the elements of our home increasingly acquire lives of their own, we become the estranged visitors in the world we have created in our own mirror image. In that sense, smart technology makes us all intruders. |

Words Reinier de Graaf

Above: First launched in 1959, Barbie has this year been given a 21st-century upgrade |

|

|

||