|

|

||

|

In his latest book the radical geographer David Harvey examines the idea of the “right to the city” and looks at ways in which urban populations around the world can reclaim the spaces that couldn’t work without them, but which they rarely control ICON You talk about how Michael Bloomberg, the mayor of New York, has reshaped the city, Manhattan most of all. He uses the positive-sounding slogan: “Building like Moses, with Jane Jacobs in mind.” But you ask: “What do you do with the people who have to be moved on?” Are you arguing for more static cities? Part of the dynamism of cities is that people move in and out. David Harvey But who is moved and who is priced out? I don’t see eminent domain [compulsory purchase] being used on Park Avenue or in Mayfair. I see eminent domain being used in regard to vulnerable populations who are advantageously located. The land is considered high value and it should go to its highest and best uses, to become office spaces or high-rise condominiums instead of living spaces for ordinary folk. There is an inherent class bias in the way in which spaces in the city are allocated. Why should we accept a system where the people who move on are the most vulnerable and the people who stay wherever they like are the one-percenters? ICON What does “the right to the city” mean in this context? And who are you referring to in New York? DH The people who build and sustain a city should have a right to residency and to all the advantages they’ve spent their time building and sustaining: simple as that. The people who come into New York City at 6 o’clock in the morning to wake the city up, and who live on $30,000 a year, have a right to the city they’re waking up. It’s not just a right to the existing city, but a right to actually transform the city so that we don’t end up with consumer palaces for the rich and high-end condominiums in the centre of the city. A lot of minority groups are moving out of the New York metropolitan region entirely, to upstate New York or out to small towns in Pennsylvania, because they can’t afford the metropolitan region any more. ICON You use El Alto in Bolivia as an example of an engaged city, where different groups have had to work out how to live together. But when you say, “You have to show up to things or otherwise you’ll get shafted”, this implies a friction that people in older cities are no longer used to, and don’t much like. Is it possible to reintroduce it? DH In the last 30 years we’ve been through this process of – I use Sharon Zukin’s phrase – “pacification by cappuccino”. It’s perfectly true that people have a non-conflictual life and to the degree that they have a non-conflictual life they disengage with a lot of what’s going on around them. But suddenly everyone gets agitated and people start talking to each other, who didn’t talk to each other before. Then things settle down and there’s a nostalgia for when we had this great togetherness but nobody can really think of a reason for it to exist again. A conflictual city is always a much more engaging kind of thing. The big problem is to have a conflictual city where people are not killing each other. You don’t want to find decapitated bodies outside the front door when you go out in the morning. The ethnographies done in El Alto showed that the solidarities, which existed, were around conflictual forms of engagement. That’s what kept everybody talking to each other. ICON What about the rate at which urbanisation is speeding up – what kinds of stresses are being applied to these new urban populations? DH I don’t want to universalise too easily: the situation in New York was very different to the situation now in Mumbai. In the last 50 years we’ve moved from a situation where about a quarter of the world’s population is urbanised, to now when it’s 50 percent or more. It’s been a dramatic, dramatic reorganisation of global populations, including the sudden growth of massive cities – anything up to 20 million – such as São Paulo, Mumbai. On the left, there was the lone voice of [urban theorist] Mike Davis who was constantly writing about these things. And I thought: why in the face of this massive transformation of daily life isn’t the left thinking about what kinds of politics will come out of this? What kinds of mechanisms of government and repression are going to be constructed around these massive populations. These huge populations, which are suddenly appearing, are very disruptive; they’ve been shunted off the countryside, they’ve been pushed in from elsewhere. It’s not as if the government sets up structures and then welcomes the migrants; governments are perpetually trying to catch up.

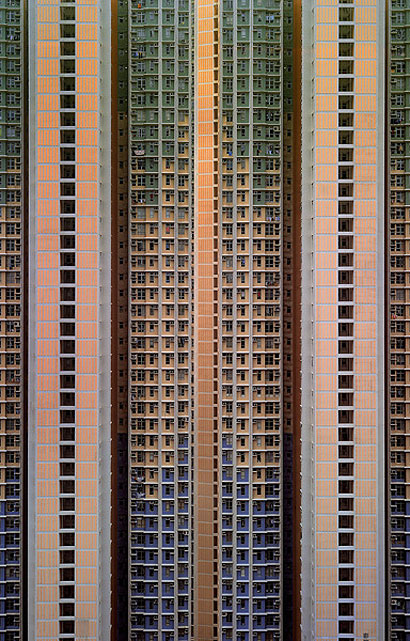

ICON China is making cities on a scale we’ve never seen before. You point out that in the 20th century, the US built homes to get the economy out of slumps, but it can’t do that any more – there are just too many empty houses. Are you worried about China ending up with empty cities? DH The Chinese are building whole cities and they’re looking for people to live in them; it’s a sort of pre-emptive urbanisation they’ve engaged in. But there are a lot of struggles going on. Even the official reports show a doubling of incidents of various kinds, and a lot of those incidents are over the displacements. There’s a great deal of instability and agitation among the population about urbanisation, as there is in the factories: Foxconn [the electric components company that manufactures Apple products and has seen a spate of suicides and protests over working conditions] and the rest of it. At the same time, they’re absorbing vast amounts of surplus capital and labour through this huge urban project, which is likely to lead to overproduction. On the other hand, the Chinese also have a surplus in their budget so they can recapitalise a lot of this. However, a lot of the municipalities are very indebted so you may see a debt crisis at the municipal level in China in the next few years. ICON How are older cities changing? How successful are their attempts to reinvent themselves? DH A lot of older cities have effectively gone under. We see “shrinking cities” in Detroit and Buffalo; in eastern Germany and also in Japan. Detroit no longer has the industrial base it once had, so it has a lot of housing which is no longer needed. It may be that the shrinking cities are going to have some alternative form of urbanisation. You see a city in this country like Manchester, which is reinventing itself. It’s not a shrinking city like Detroit; it’s coming out of its 1980s de-industrialisation. Throughout Europe, there’s been a model of entrepreneurial cities trying to turn themselves into growth poles for their region. I was in Spain, maybe four years ago, and I rode the high-speed train. I was going through these cities and counting the construction cranes, in Madrid and Valencia and Seville … At the time I said, “But this is crazy,” and everyone laughed and said, “Yes it’s crazy, but we can’t do anything about it.” Now we’ve got the problem. ICON What’s the most pressing thing for urbanists to be thinking about now? DH Capitalism is in a great deal of trouble, so the models of urbanisation we see are either in a great deal of trouble, or they will be. We have to think about an alternative model of urbanisation which is going to take us away from accumulation for accumulation’s sake and production for production’s sake. ICON How does global warming affect urbanisation? What kind of cities should we be living in? DH We cannot diminish our use of cheap fossil fuels without transforming the suburbs and the suburban lifestyle. If the suburbs were poor, we’d simply say: get out of here, we’re going to remodel all of this. But we’re dealing with an entrenched interest, which doesn’t want to change the suburban lifestyle even if it’s sympathetic to the question of global warming. If you want to see all the problems I’m talking about in exaggerated form, go to China. There’s no question about the environmental consequences of the form of urbanisation they’ve had until now: they had to stop the traffic in Beijing for two weeks before the Olympics. The Chinese are very aware of it so they’re taking up the question of air quality and water quality. What is a slow creeping set of problems in Britain, in China is dramatically posed. And the Chinese also have the possibility of saying, well, we’re going to find an anti-capitalist version of this. I doubt they’re going to do it, but they still have the possibility of doing it. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution is published by Verso Books |

Words Fatema Ahmed

Image: |

|

|

||