|

|

||

|

It may seem strange that San Rocco has won an architecture prize given that it is not an architectural practice and its only outputs are made of paper. But it is a tribute to the alliance behind it that this award is given despite these seemingly cardinal restrictions. San Rocco represents something vital about contemporary architectural practice. The network of architects, graphic designers and photographers behind the modest, black-and-white covered publication has come together around shared interests that buck the prevailing tendencies of architecture and propose a new model of practice. And all of this in what is supposed to be a side project in a time of publishing’s decline. San Rocco is, in fact, the name of a place in Monza, Italy, where, in 1971, the two Italian architects Aldo Rossi and Giorgio Grassi collaborated on the design of a housing scheme that was never built. It is an inspiration to the group behind the magazine because, they say, it “was the product of the collaboration of two young architects. San Rocco did not contribute to the later fame of its two designers. It is neither ‘standard Grassi’ nor ‘standard Rossi’. Somehow it remains between the two, strangely hybrid, open and uncertain, multiple and enigmatic.” For San Rocco the magazine, these things make it a compelling cornerstone for its own work.

The practices behind the magazine are centred around Milan, but not all are there, and the dispersed nature of the group is part of its interest. The founders are: 2A+P/A, the Rome-based office founded by Gianfranco Bombaci and Matteo Costanzo; Baukuh, the Milan outfit of Pier Paolo Tamburelli, the photographer Stefano Graziani; the Brussels-based Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen; Milan graphic design studio pupilla grafik, young Milan practice Salottobuono; and Milan photographer Giovanna Silva. Tamburelli says that the magazine was conceived as a temporary project. “We wanted to create a magazine, and a little debate, and from the beginning we planned to do 20 issues, no more than that. It is a project that will expire.” This temporary collaboration is framed as a part of architectural practice, and Tamburelli says that it seems “obvious” that to be a culturally relevant architect, you need to write. “It’s not an academic magazine,” he adds. “It’s produced in four months. It’s different to the rhythm of architectural production, it’s more like doing a competition: you never get more than two or three months.”

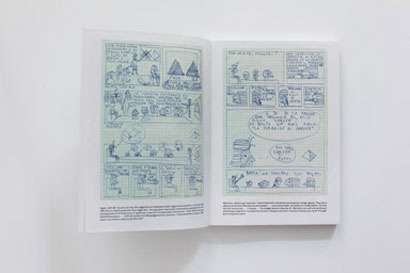

Most interesting is how the magazine generates its content, through a call for papers in every issue, asking readers to contribute to the next according to a set theme. “It’s a magazine where the authors and the readers coincide, almost anyone reading the magazine could consider writing in it,” says Tamburelli. Each theme (examples include Islands, Mistakes and Fuck Concepts! Contexts!) is unpacked at length in the call for entries, showing the breadth of interests of the group, and how they use the magazine as a kind of crowd-sourced enquiry. This call for entries is not for the faint-hearted, weighing in at 11 pages. But it ranges pleasingly from the work of Italian modernists such as Giuseppe Terragni to Renaissance architecture to the question of whether Philip Johnson was a good architect. At last year’s Venice Biennale, San Rocco made its call for entries into a 3D display of models, publications and statements. My favourite was a model of the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building, the interior of which was designed by Johnson, complete with the Mark Rothko paintings that were never hung in the real restaurant. In the foreground, if you looked closely, the Kennedy party was in full swing, with Marilyn Monroe singing “Happy Birthday, Mr President”. The writing in the magazines is of a high quality, but Tamburelli plays down the amount of editing that goes into each issue, and describes their success as “surprising”. San Rocco sells 3,000 of each issue, which is almost as high as some mainstream design magazines, making it an influential voice. Perhaps what is most heartening about San Rocco is that the people behind the magazine are happy to bring their differences with them, but also confident enough to speak with a single voice – the editorial voice. Their most recent call for entries states: “San Rocco believes that architecture is collective knowledge, and that collective knowledge is the product of multitude.” Nothing is sacred, but equally, nothing is to be dismissed. San Rocco’s attempts to reinstate architectural discourse are well worthy of a prize dedicated to emerging architecture. |

Image Piero Martinello; Stefano Grazani

Words Kieran Long |

|

|

||