|

|

||

|

Amid the showiness of contemporary high-profile architecture, this Ghent-based practice stands out for its thoughtful, sensitive and reticent approach to existing buildings and its original designs Out of the shortlist for 2013’s Mies van der Rohe Award, one project stood out – or you could say, stood in. The winner, Henning Larsen’s Harpa Concert Hall in Reykjavik, and the other shortlisted buildings were all dramatic standalone structures with easily grasped identities – par for the course for architecture today. But Robbrecht and Daem’s Market Hall in Ghent was harder to understand – a sophisticated piece of urban design in a hyper-sensitive medieval context; a slow-cooked and considered work of architecture that drew on its historical surroundings. Spectacular is certainly not the word for it. “We felt a little bit like foreigners – the strange people in the group of nominees,” says Paul Robbrecht, who heads the firm with his wife Hilde Daem. Theirs is an architecture of subtlety in a world of big gestures. The central Ghent redevelopment, a project that kicked off in 1996, involved everything from re-routing tramlines, digging new underground facilities, creating a bell tower for the cathedral and building the hall itself, formally drawn from Flemish precedent and offering a large yet intimate urban experience.

Last year, the practice also realised a mock-up of an unbuilt 1930 project by Mies van der Rohe – a clubhouse for a golf course in Germany – a few hundred metres from where it would have been. “If it had been built, it would have been one of his masterpieces, “Robbrecht says. The original was an expansive, flowing space freed up by steel framing, luxury materials and full-height glazing. “The most wonderful thing to do was read his plans,” Robbrecht says. “It’s the same joy as reading a music score and then hearing it in your head.” Robbrecht and Daem’s project was part building, part model, part ruin. Mies’ seminal cruciform columns are there in polished steel, but all other materials are simplified – concrete paving stones, gravel, exposed timber panels and, a clever touch, polished plywood, whose grain stands in for Mies’ signature onyx. It has already been demolished, but was easily an architectural highlight of the year. This unshowy, but deeply considered approach is apparent throughout the firm’s work. A sculpture pavilion in an Antwerp park from 2012 sets contemporary art off against a green, latticed-steel roof, an odd but compelling synthesis of “white cube” and horticultural folly. The recent refurbishment and extension of the Whitechapel Gallery in London (with Stirling Prize-winner Witherford Watson Mann) is so subtle as to be almost invisible. Existing buildings are a frequent source of work – be it the City Archives in Bordeaux, in an existing building’s shell, or the Film Museum in Brussels, nestled under a Victor Horta building.

Not everything Robbrecht and Daem has done is quiet, though. Its concert hall in Bruges in 2002 is large and forcefully massed, its envelope folding around the auditoriums and flytowers, but at the same time the result of deep familiarity with the peculiarities of the Unesco-protected site. “It is true that the important projects we are working on need a lot of consideration,” Robbrecht says. “Building in Bruges, for instance, where nothing contemporary has been built in 300 years, or in Ghent, where it’s right in the heart of the city. If we weren’t interested in the historical towns we live in, we would never have convinced people it could be done.” Indeed, the market hall, which ties all the strands of the Ghent project together, was not part of the original brief, and came from the architect’s suggestion that the fabric of the city in that location actually demanded it. What gives Robbrecht and Daem’s work its power is perhaps this mix of contemporary and historical sensibilities. “We are always interested in the ability of architecture to be a place where dialogue could happen within the work, or where the work could give shelter to that dialogue,” Robbrecht says. This isn’t just idle chat – the practice’s collaborators include the painters Gerhard Richter and Luc Tuymans and it has also worked for the Documenta Festival in Kassel. As well as the Mies Clubhouse, it is refurbishing the Ghent University Library, a 1930s work of Henry van de Velde, and has begun work on refurbishing a Marcel Breuer building in Rotterdam.

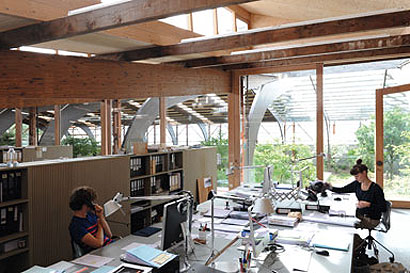

But what might actually be Robbrecht’s favourite project is one very close to home. “Our office is a paradise,” Robbrecht says, permitting himself a rare moment of hyperbole. “It’s like a utopia that came true!” Scouring around for a new space in 2005, they came across a timber yard in a run down part of Ghent. “I immediately knew it was our place,” he says. The offices themselves are in one wing, while the rest of the partially demolished warehouse has been given over to an arboretum, a garden and a pool. It’s a perfect example of the firm’s approach: considered, thoughtful, historically enriched, while maintaining a contemporary design ethos. It would be nice to think that after so many years of purely spectacular architecture dominating, we’d give more time to architects such as Robbrecht and Daem, who are playing a more mature game. |

Words Douglas Murphy |

|

|

||