|

|

||

|

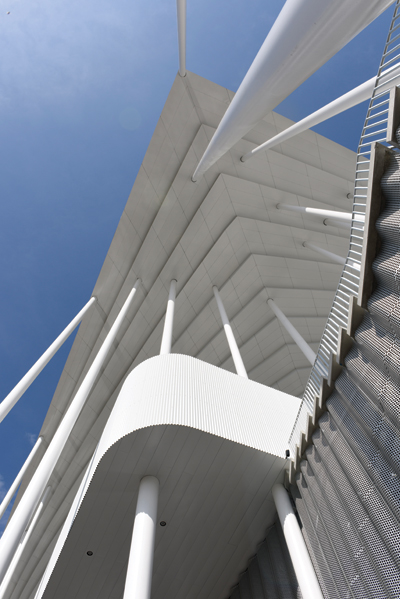

The Swiss architect’s latest stadium brings classical gentility to the world of football, but is still robust enough to withstand 42,000 fans As Pierre de Meuron stands outside the players’ tunnel at the Nouveau Stade Bordeaux, it’s easy to suspect he is there as a football fan first, the building’s architect second: “Stadiums are very important to us. You have a team, then you have a passion and you have a virus – and when you have it, you don’t get rid of it.” This passion has been a defining factor in Herzog & de Meuron’s previous stadium work – not just St Jakob Park, designed for their beloved Basel FC, but also the flamboyant Bird’s Nest in Beijing and the bulbous Allianz Arena in Munich, with its celebrated coliseum-like intensity. It is therefore surprising that, for Bordeaux, H&dM appears to have created a stadium that is light, elegant – even genteel. While the Allianz Arena proudly wears a team shirt, its ETFE cladding glowing in Bayern Munich colours on match days, it isn’t immediately clear that the Nouveau Stade Bordeaux has anything to do with football at all. Arriving at the entrances on the east and west facades, supporters are greeted with a forest of slender white-painted columns that veil the stadium bowl. This discreet portico nods to the neoclassical elegance of Bordeaux’s Unesco-protected centre, a few kilometres further up the Garonne river, creating an unusual spectacle in sport: a stadium with precise corners. The right angle at which the roof meets the corner columns is as delicate as a line drawing. H&dM does understand the theatricality necessitated by any stadium approach, however, and handle it here with a flourish. A white-painted concrete stair stretches the length of both entrance facades, reflected in the stepped underside of the bowl above, drawing fans up to the five large entrances where the two sides of the mirror meet. Here, they immediately encounter another impressive setpiece. Food concessions, bars and toilets are usually hidden away in the bowels beneath the lower tier, but H&dM has raised them up to the fourth level on a generous belt-like loop around the stadium. Supporters can take their half-time refreshment looking down on the pitch or back out to surrounding parkland and the open skies of the Gironde estuary. This is less a service area, more a promenade, the predominance of white-painted steel rather than concrete in the structure adding to the sense of lightness. “Architecture cannot guarantee good football or a victory but it can create a setting that is more or less agreeable or convivial or attractive, and perhaps release or control the emotions,” says de Meuron. Here, it initially seems that emotions are on a tight rein. The palette for the concourses is all white, a muteness that continues into the bowl itself. The spandrel panels that face the second tier are a light, fair-faced concrete, while the seating is a random pixellation of grey and white tones. The flat, translucent roof, which protects all 42,000 seats from the rain, is also determinedly neutral, with its immense steel structure neatly tucked away, above and in the upper section of the bowl, so as not to distract fans’ attention from the pitch.

It is hard not to detect a slightly corporate feel to all this understatedness. The stadium has been built as one of the key stages for next year’s European Championships, in addition to providing expanded facilities for the local Ligue 1 club, Girondins de Bordeaux. But it is also a “multifunctional venue” placed conveniently next to the Aquitaine département’s largest exhibition centre and equipped to host a range of business events. The ribbon of corporate hospitality boxes between the bowl’s two tiers is a reminder, too, of how modern football makes its money – the Girondins hope to triple hospitality takings when they move from their existing stadium, an art deco former velodrome opened in 1924. But 42,000 football fans can do much to stamp out the whiff of corporate sterility, and that’s exactly what H&dM intends. The palette may be muted but, as de Meuron points out, “it is the spectators who provide the colour”. They also provide the noise, and in this they are ably abetted by the architects. The seating begins just 6.5m from the pitch, making the interaction between fans and players “as immediate, as close, as intense as possible”, and the two tiers overlap so that even the upper rows are bearing down on the action. The roof also adds to the din, its undulating surface reflecting the crowd’s roar down into the bowl. H&dM has created a stage for key moments: the swell of expectant fans climbing the full length of the facade, the transition from the open concourse to the intensity of the bowl, and ultimately the match itself. The materials and detailing throughout are functional rather than refined: a white-painted mesh surrounds the ground level, offering glimpses of the backstage infrastructure, while the fourth-level concourse is unprepossessingly clad in corrugated steel and the joints between the aluminium panels on the underside of the bowl are starkly expressed. But ultimately, this building is not about the details. “A stadium is not a jewellery box,” says de Meuron. “It’s real, it’s life. It needs to be robust. A stadium is a really tough world and you need to understand how it works – we are fans so we know what we are talking about.” The Nouveau Stade Bordeaux may appear highly civilised but, at heart, it’s still a bit of a coliseum. |

Words Nick Jones

Images: Iwan Baan; Vigouroux – Perspective |

|

|

||

|

|

||