Tony Ray Jones, Pepys Estate, Deptford, London, 1970. Credit: Tony Ray-Jones / RIBA Collections

Tony Ray Jones, Pepys Estate, Deptford, London, 1970. Credit: Tony Ray-Jones / RIBA Collections

The fuzzy language of wellness and the lust for ever longer lives has hindered a history of promoting public health through architecture, writes Debika Ray

Between the 1980s and the early 2000s, artists and philosophers Madeline Gins and Shusaku Arakawa designed a series of experimental architectural structures in an effort to articulate their theory of ‘reversible destiny’. Design, they argued, could allow humans to curb the ageing process and ultimately defeat death itself.

Through projects such as the Bioscleave House (Lifespan Extending Villa) in New York (2008) and the Reversible Destiny Lofts in Tokyo (2005), they suggested that environments of instability and unpredictability – with labyrinthine accessways, undulating floors you move around with the help of vertical poles – could strengthen the immune system and prolong life indefinitely by forcing you to actively engage with even the simplest of tasks.

Arakawa died in 2010, and Gins a few years later. In so doing, they failed to achieve their greatest ambition. But the quest for immortality continues unabated. It is still generally accepted that humans can’t live past about 125, but life expectancy has risen exponentially over the past two centuries so it is not difficult to see why eternal life continues to be a preoccupation.

In recent years, several major tech investors have revealed an interest in anti-ageing research, and a host of bio-research start-ups have emerged in Silicon Valley, looking at everything from growing new organs to infusing older people with the blood of the young.

As of July 2018, the Alcor Life Extension Foundation, a cryonics lab in Arizona, has 159 ‘patients’ who were frozen after death. Meanwhile, advances in robots, artificial intelligence and nanotechnology present the possibility of living on indefinitely in digital or machine form. Clearly, there is a market for longevity, but it remains to be seen whether death is simply a bodily malfunction that can be avoided with the right scientific tools.

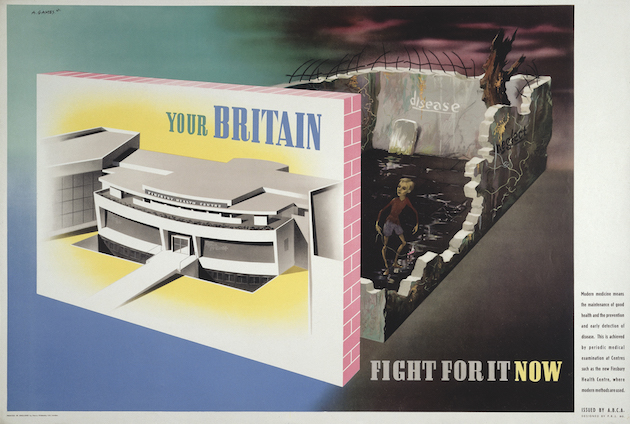

Your Britain: Fight for it now, Abram Games, 1942. Credit: Wellcome Collection

Your Britain: Fight for it now, Abram Games, 1942. Credit: Wellcome Collection

Undoubtedly, architecture has played a role in extending our lifespans. Living with Buildings, an exhibition opening at the Wellcome Collection in London this October, traces the historical relationship between health and the built environment, mainly in the UK. It focuses on the ambitious built projects that have accompanied our spike in life expectancy since the 1800s, looking at how they have shaped our present-day ideas about health.

For example, villages built by factory owners for their workers in the 19th century offered vast improvements on the overcrowded, unsanitary conditions of many inner-city areas, but at their heart was also a paternalistic attitude towards residents. Saltaire in West Yorkshire, built by cotton mill owner Titus Salt, offered housing, a hospital, schools, parks and churches but, crucially, no pubs; likewise at the Bournville estate – developed by George Cadbury near his chocolate factory in the Midlands – residents were issued with rules and dietary advice for a ‘healthier and therefore more cheerful life’. These included not eating between meals and sleeping in single beds; and later, guidelines for young people on ‘looking ahead’, ‘care of money’ and even ‘being a gentleman’.

The health problems we are facing today are a world apart from those of the 19th century, but there are echoes of this top-down attitude to employee health (and hence productivity) in the current preoccupation with employee wellness in the corporate sphere. It is also clear that health priorities have always been unevenly applied across social lines – for example, the high walls of the Bedford Park garden suburb in west London revealed the comparative attitudes of middle-class communities. ‘It was as much about what it was keeping out as it was about what was inside it,’ the exhibition’s curator Emily Sargent observes. ‘There is a political thread that runs through a lot of these conversations because inevitably the conversation about buildings and health is about social divides.’

Life expectancy continued to improve in the 20th century, alongside the rise of utopian modernist ideals that design and scientific progress could transform society. In promoting good health, architects deployed cutting-edge design that brought in light and ventilation, as well as reasserting the holistic notion of health that was implicit in projects such as Saltaire and Bournville. Among these were the Peckham Pioneer Centre by Owen Williams, an experimental facility where families had their health monitored, but also engaged in social interaction and community activities – all under the watchful eye of its founders. Bauhaus luminary Walter Gropius called it an ‘oasis of glass in a desert of brick’, and its open plan, cork floors for walking on barefoot and large swimming pool promoted preventative, rather than reactive, health.

Steffi Klenz, Nonsuch, 2006. Image: Steffi Klenz/Wellcome Collection

Steffi Klenz, Nonsuch, 2006. Image: Steffi Klenz/Wellcome Collection

Berthold Lubetkin’s celebrated Finsbury Health Centre landed in a deprived inner-London community in 1938 with the objective of bringing free universal healthcare to ordinary people. Facilities were included to disinfect bedding and clothing, and to provide services such as podiatry, dentistry and maternity care. The architect said that the ‘curving facade and outstretched arms were intended to introduce a smile into what in fact is a machine’, while its light-filled, airy interior with colourful murals was designed to inspire people to live healthier lives.

Similar ideals guided the design of the 1933 Paimio Sanatorium in Finland, described by its designer, Alvar Aalto, as a ‘medical instrument’ – which offered views of the nearby forest, soft lighting and specially designed no-splash sinks so patients would not disturb each other. The building’s richly coloured interiors were a statement of the healing power of an aesthetically pleasing interior, as were those at the Herlev Hospital in Denmark, by artist Poul Gernes.

The connection between health and our environment is reflected today in the work of designer Morag Myerscough, who has brought her trademark bold graphics to the interiors of Sheffield Children’s Hospital and the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. ‘For me, it was about transforming what’s a pretty scary and clinical space into an area that feels more homely and doesn’t feel institutionalised,’ she says.

The Maggie’s cancer care centres are perhaps the best-known contemporary examples of architecture deployed in the pursuit of better health, with Richard Rogers, Zaha Hadid and Rem Koolhaas among their designers. The brief reflects the notion that care in these contexts is about more than medicine. ‘Maggie’s centres should help to coax people out of their isolation and help them to feel less locked in,’ Myerscough says. ‘Within that is the need for spaces that make it easy for people to talk to each other and feel less alone while also considering the degree to which people want to be private, to offer corners to tuck up in with a book, and places where they can sit and watch, but not necessarily join in.’

In recent years, there has been a shift in rhetoric that has resulted in a conflation between the meaningful attempts to generate architecture that improves and extends our lives, and the notion of ‘wellness’, a word often used to denote the active pursuit of a better life. In many cases, the latter reduces human wellbeing to a lifestyle choice – one that can be achieved, bought, sold and consumed by those who have the time and the means.

As a result of the wellness craze, offices now offer lunchtime yoga and biophilic design; luxury hotels employ circadian lighting; and our notion of comfort even in a clinical setting is modelled on the idea of a spa. The dominance of the wellness rhetoric in everyday life also presents problems. ‘One is that we have very nebulous ideas of what wellbeing is,’ says Jo-Anne Bichard, a senior research fellow at the Royal College of Art. ‘My idea of wellbeing could be completely different to yours and it’s not something that can be measured. So who are we designing for and how do we find a middle ground?’

The result of this fuzziness is that wellness has superseded genuinely healthy architecture, to the detriment of everyone but a narrow segment of society. ‘We still see much of our cityscapes built from a very male, able-bodied perspective that forgets that not everybody is of a certain socioeconomic class,’ Bichard says. ‘Our cities mostly comprise private spaces that are maintained and guarded, so wellbeing becomes something that can be monetised in some ways, with certain spaces better than others.’

This language of wellness dovetails with the interests of the Silicon Valley immortalists and the cryonics enthusiasts in that it views health not as a communal pursuit but an individual one. Just as we track every fluctuation in our body through wearable devices and smart technology, the quest to live forever requires us to view death as a problem that has a technical solution – one that will one day be bought by those who can afford it.

On the contrary, perhaps there’s an inherent incompatibility between longevity and sustainability. ‘Part of the wellbeing agenda keeps being appropriated by the fear-of-death crowd, rather than the quality-of-life crowd,’ Bichard says. ‘We have a lot of problems at the moment because we have an ageing population, so maybe we shouldn’t be making everybody live longer, because another year we spend on the planet is another year using up resources.’ In the pursuit of a healthier planet and ultimately more sustained health, perhaps it’s time to pull the plug on the quest for eternal life.