Peter Barber at his Kings Cross studio. Photo Kevin Davies.

Peter Barber at his Kings Cross studio. Photo Kevin Davies.

Peter Barber has brough both quality and sociability to London’s social housing, with a string of characterful schemes enlivened by terraces, colonnades and colourful entrances…So, what’s with the monorail, asks Will Wiles.

‘It’s a peculiar one,’ Peter Barber says the first time we meet. He’s explaining why the interview had to be on this day in particular – tomorrow he’s o on a four-day expedition. Starting in Croydon, Barber and the filmmaker Grant Gee plan to cycle in a giant loop around London, a journey of 100 miles. The aim is to survey the ground for the Hundred Mile City, Barber’s modest proposal for ending the housing crisis: a belt of high-density low- rise homes surrounding the capital, joined up by an orbital monorail. ‘It’s all about the densi cation of suburbia, by which means we could easily solve the housing crisis,’ he says. ‘We shouldn’t be allowing London to sprawl further, we shouldn’t be demolishing social housing in Camden.’

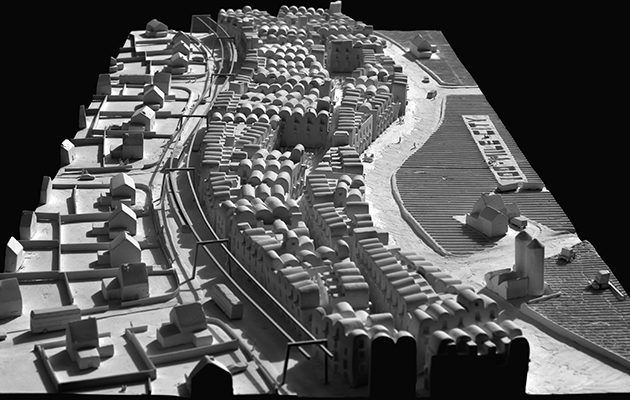

A model of the sample slice of the Hundred Mile City shows a labyrinthine band of barrel-roofed terraces with a medina-like feel. On one side are the semis of suburbia and on the other is open farmland. It’s the latter that has Barber’s attention, and he’s thinking about ways of replacing low-productivity agribusiness with smaller farms and market gardens serving local markets in his new urban belt. Architects tend to be shy of this kind of total planning nowadays, I suggest – it harks back to utopian proposals such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City, or Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin. Barber demurs: ‘I’d say it’s idealistic rather than utopian.’

Idealistic, then. That strikes at the heart of the paradox of Peter Barber. He’s certainly idealistic, but what’s exciting about him as an architect is that he gets things done. His practicality, and the built results he achieves, are the really radical and exciting things about him.

Holmes Road Studios, a homeless facility in north London, completed n 2016. Photo: Morley Von Sternberg

Holmes Road Studios, a homeless facility in north London, completed n 2016. Photo: Morley Von Sternberg

His métier is social housing in London, a subject quite capable of inducing despair – but consideration of Barber’s work instead leaves one hopeful. Holmes Road Studios, a terrace of small transitional apartments for homeless people, is not only humane, it’s cheerful and enticing. On a much larger scale Pegasus Court in north London has 70 apartments, but its genially varied mass and sedate colonnade only invite the visitor to wonder what Barber might be able to achieve given much more of the city.

This ability to come up with the goods when other idealistic architects have to make do with what-ifs has made Barber very popular. A few days before we met, he spoke at the Architecture Foundation, and filled every one of the 700 seats available. Though he has won awards for more than 20 years, the past year or two has seen a sudden torrent of interest and favourable coverage. Does it feel like a breakthrough? ‘Even six months ago, before the [Architecture Foundation] talk, if somebody said you’d sell out, it would have been quite a surprise,’ he says. ‘Since then I’ve been asked to talk in Istanbul, in Sri Lanka, in South Africa and in Glasgow.’

There’s a touch of Samuel Beckett in Barber’s appearance, though with none of the gloom. His attire has an unexpected decorative touch: a jewelled scorpion brooch. ‘It’s usually a lobster, the lobster of knowledge, but I lost the lobster,’ he says, as if that explains it. His practice operates out of a tiny Dickensian shopfront in King’s Cross, which he found about 15 years ago – with creaking floorboards and a steep, broom-cupboard staircase, it’s a surprise it has survived the tide of regeneration that has engulfed the area. He has his own scheme in mind, though: ‘We’ve got a plan to dig out under the forecourt and open a music club,’ he says. ‘For world music and jazz.’ Why? ‘Because it’d be fun. And I love music.’ It’s a musical practice, he says – there is already an office piano and drumkit.

The 100 Mile City, Barber’s proposal to surround London in a belt of low-rise homes.

The 100 Mile City, Barber’s proposal to surround London in a belt of low-rise homes.

A Victorian terrace entirely suits Barber. Beyond their social promise, what his recent projects share is their investment in townscape and charismatic use of brick. Far from the stuck-on brick panels of the volume housebuilders, Barber’s bricks exude swagger and solidity. The long courtyard of his employment academy in Southwark is capped with a handsome brick exedra, bringing a touch of Isfahan to SE5; his Worland Gardens apartment building is fronted by a springy series of parabolic arches. In some cases he appears to be using brick to joyous (or even satirical) excess – the brick cladding at Grahame Park and the Hafer Road co- housing project in Wandsworth extends to the underside of the balconies.

But if the average architecture fan would today associate him with brick, ‘they certainly wouldn’t have done that in the first ten years of the practice,’ he says. After studying at the Central London Polytechnic, he worked for a diverse selection of practices, including Richard Rogers, Will Alsop and Jestico & Whiles. At the time, he says, his interests were ‘high-tech-y’, but all that changed when he went to an exhibition of the work of Mexican architect Luis Barragán at the Architectural Association: ‘Solidity, mass, the poetics of light … I always liked Le Corbusier but that was a bit of a moment.’ Liza Fior of Muf introduced him to the work of Álvaro Siza, who was still relatively unknown at the time, and the aesthetic conversion was completed.

His first significant project was a large white-rendered villa in Saudi Arabia in the mid-1990s, where he served as project foreman as well as architect, ‘bartering for batches of cement and looking after a team of 20 people on site. Everything has seemed fairly straightforward since then.’ He brought back a love of white render, and it dominates his earlier projects, such as Donnybrook Quarter in Hackney, completed in 2006.

Donnybrook was one of Barber’s earlier projects, before he started using brick. Photo: Morley Von Sternberg

Donnybrook was one of Barber’s earlier projects, before he started using brick. Photo: Morley Von Sternberg

The shift to brick happened a couple of years later, and his cited reason is completely practical: render doesn’t get properly maintained by landlords, especially cash-strapped social landlords. ‘Donnybrook they’ve looked after well,’ he says. But he names another large project in east London that ‘hasn’t been painted ever, in 12 years, and it just looks awful’.

Thinking about materials that were less reliant on maintenance led him to brick, although it’s not a cost-paring measure, as it’s good brick that ages best, so clients have to be persuaded to make the investment up front. But they clearly are persuaded. And it wouldn’t be Barber if this practicality wasn’t adorned with some whimsy, and a magpie-ish list of in uences. Expanding on his enthusiasm for brick he cites the vernacular of his native Surrey, arts and crafts architecture, Uruguayan engineer Eladio Dieste, Louis Kahn and his grandmother’s crinkle- crankle garden wall.

Housing attracts him as a way of expressing his broader ideas about the city. ‘Everyone talks about the street,’ he says, ‘but pretty much 70% of all buildings in London are houses or housing. The city is pretty much made of housing, it’s what compresses public space and the street, it surrounds squares. So that lies at the heart of what we do. I spend a long time thinking about front doors and public space and what encourages people into a sociable environment in the streets.’ The buildings wear this on their sleeves: courtyards, terraces and colonnades are as characteristic of Barber as brick. He works hard to squeeze as much density as possible out of sites, even by reviving typologies that have fallen into disrepute: in Newham he is experimenting with back- to-back. His larger-scale proposals, such as Coldbath Town, for the controversial Mount Pleasant site in north London, have a teeming, brimming feel. Fundamental to this are his e orts to reconcile the desire of Britons to live in houses – rather than flats – with the need to avoid, wherever possible, building on the countryside. ‘A lot of our projects are apartments, but they have the feel of houses. That’s because of things like having front doors along the street, like the old cottage flats.’

Pegasus Court at the Grahame Park housing estate in London. Photo: Morley Von Sternberg

Pegasus Court at the Grahame Park housing estate in London. Photo: Morley Von Sternberg

His interests in streets and front doors, and brick, put him in tune with the New London Vernacular, the capital’s dominant housing idiom since former mayor Boris Johnson’s design guide was published in 2009, but this is more a happy convergence than a deliberate policy on Barber’s part. And his justi cations for his repeated tropes always loop back to the experiences of residents, rather than aesthetics. The expressive arches at Worland Gardens are to entice people to use the balconies at the sunny, south-facing front of the building, and bring some life to the street. Colonnades, which creep into Barber designs wherever possible, he calls ‘a very sociable way of meeting the ground’.

‘We need columns,’ he says of the square he is laying out at Grahame Park, which has a ‘tasty colonnade’ in the Jamie Oliver-ish language of his website. ‘It has these curious Minoan columns that are circular at the bottom and elliptical at the top.’ These, and the irregularly spaced balconies, are partly to add some visual complexity to a large building, for picturesque reasons. But he also wants to invite complexity that others discourage. ‘Some architects and clients hate the fact that people put things out on balconies and so on, but for me a building is nothing untilit has life breathed into it by the activities of its occupants. So I’m hoping that when we go back this will have mess all over it.’

The second time we meet is in the lobby of the Bartlett School of Architecture, where some of Gee’s footage from the Hundred-Mile odyssey (Croydyssey?) is on display. The lobster has reappeared.

Worland Gardens, an arcaded terrace of townhouses in Stratford, London. Photo: Morley Von Sternberg

Worland Gardens, an arcaded terrace of townhouses in Stratford, London. Photo: Morley Von Sternberg

What has bothered me, since our first meeting, is another Barber paradox. He is unquestionably progressive in his politics, calling for hugely increased spending on social housing, an end to the right to buy and rent controls on private landlords. But his urban model – streets, squares, brick, low-rise – is one most associated with reactionary architects and pressure groups, such as Create Streets, an offshoot from a hard-right think tank. Does that bother him? ‘My inspiration is very much [American theorist and writer] Marshall Berman, who was an out-and-out Marxist, so that would be my answer to that,’ he says. In our previous chat, he had quoted Berman: modernism exists in our streets, and in our minds. Barber continues: ‘I think he understood the social benefits of collective living, making viable streets like that.’ Nevertheless, he does find the overlap with the traditionalist right ‘a bit annoying, you’re right about that. They like all my posts!’

What was Barber’s impression of the periphery? A suitable canvas for his grand project? ‘It wasn’t very convenient,’ he says. ‘My nice neat line didn’t exist. But the amount of green space out there – I’m not talking about proper green belt, I’m talking about vast green verges and motorways with loads of space alongside them – there’s tonnes of space out there, and the film bears testament to that.’

Gee’s forthcoming film will explore the proposal in more detail. But how serious is he about it? The monorail, in particular, feels like a signal that it might be more speculative than practical. He admits it’s a fantasy ‘to some extent’ – a project to escape to, ‘where one isn’t bombarded by functional constraints. But I do these projects in my sketchbooks, and they creep in to stuff that’s in the office. We’re doing a project a bit like this in Greenwich, it’s the first fragment of the Hundred Mile City, built in an area of two-storey semis.’

And he’s perfectly serious about the monorail, although he concedes it’s ‘a bit boy’s toys’. He takes as a model the German city of Wuppertal, which has a unique, 19th-century overhead railway called the schwebebahn. ‘The way it goes over streets without disrupting streets – it’s quite magic.’