|

|

||

|

Icon This issue of Icon is on the megastructure. Your recent work includes projects on a very large scale but when we requested our interview, you told us that you don’t like the word “megastructure”. What’s your beef with it? Steven Holl Megastructure is not a word that I’m very excited about. It’s a 1960s word that’s full of bad examples and bad memories. The megastructure came out of a late modernist penchant for expressing structure before anything else. Our aims are quite different from that. I’m arguing for hybrid buildings. It’s the mix of the programme and the urban life that depends on that mix, not how the structure is expressed that matters to me. My emphasis is on programme, architectural space, and public space. In the case of a building like the Horizontal Skyscraper in Shenzhen, we end up with structure being not so much expressed as hinted at. This serves as a vehicle for freeing up the ground space but it’s not expressing the structure; it’s not a megastructure. Icon Structural expressiveness is still the departure point for many architects today but I agree with you, it strikes me as nostalgic, a way of aligning with modernity, justifying architecture by appealing to the heroic efforts of the factory worker. But we’re in another era now, in a world dominated not by manufacture as much as by flows of information and finance. In other words, ours is a more ephemeral, even invisible, layer of activity. This is something that’s really interesting to me about your buildings: how for you the dimension becomes key … SH … and the ecological. Icon … and the ecological as well. I’m fascinated that you’re thinking about a new era, not an older industrial order. SH Absolutely. To me, the hybrid buildings we are doing are completely different animals. That’s why I wouldn’t use the word “megastructure”. Icon Can you elaborate on what you mean by a hybrid building? SH Hybrid buildings are the creation of a city within a city. We set out to create not just a building but a public space. It’s important not to privatise the space, but to make it public – especially in China. Take the Sliced Porosity Block, which is under construction in Chengdu. The clients had a track record of putting a shopping centre at the base of their structures and then putting up a tower of condominiums and a tower of offices. We said that we weren’t interested in that, we wanted to make a public space and connected it in a micro-urban way around the edges. We set out to make a large public space (it’s a little larger than the Rockefeller Center) with three water gardens inspired by the ancient poet Du Fu, who lived in Chengdu. He said, “This fugitive between earth and sky / From the northeast storm-tossed / To the southwest, time has left / Stranded in three valleys,” and that’s what these gardens are. There will also be micro-urbanistic elements embedded in the facade, like the pavilion by Lebbeus Woods. The form of the block comes from the path of the sun, which actually slices the block. The local code requires two hours of direct sunlight in every apartment. Icon How do you work with public space in your buildings? Is there something specific to your approach to public space in China? SH I’m always working with public space but the three large examples of forming public space all occur in China. There’s the scale of some 4 million sq ft of public space in Chengdu. At the Horizontal Skyscraper in Shenzhen some 75,000sq m of tropical landscape is open to the public. The original plan for that had only about 28,000 or 30,000sq ft of public space and we doubled that. In the case of the Linked Hybrid [in Beijing], there’s always been a struggle. The owner wants to privatise the public space and after we completed the project he erected a wall with guards at the entrance. But we put the cinematheque and shops inside, near the water garden in the public space to defy his ability to close it. We are fighting and angling for making public space in China. I see public space as the DNA of democracy that they need. Our hope is in the long term they’ll open up and become a better society.

Icon Another structure word that’s received much attention today is “infrastructure”. Some of your earliest works engaged directly with infrastructure, for example, adopting the appearance of inhabitable bridges. Referring to infrastructure is all the rage now, yet I sense that you’ve moved away from that. SH Well I’ve always been interested in anything that engages the experience of moving through space on a phenomenological level. I’m interested in how architecture can be a catalyst on your emotions and your thinking. I’m still interested in infrastructure but I’m interested in works in which the architect can shape public space instead of letting the process drive the architect somehow. The work in China has been enormous in its demands and I’m looking forward to realising works on a smaller scale where I can deal with such issues. Icon You’re employing different scales in the hybrid buildings, but you’ve also made a number of noted buildings that are much smaller and you suggested that this interests you greatly. How do you operate at different scales? SH I am very excited about the smaller scale. In terms of light, space, perspectival overlap, time and the nature of materials. At the scale of Le Cité de l’Océan et du Surf, our new museum at Biarritz which we did in collaboration with Brazilian artist Solange Fabião, you can really engage with matter closely. This is for a surf museum whose charge is to educate people about the health of the ocean. Here I’m interested in fusing landscape urbanism and architecture, working with these in a singular way right from the beginning. The building form is about the sea, the sky; it sits under the sky and next to the sea. We began with the notion of shaping the public space that addresses the sea: the building cups the sky, focuses it down toward the ocean. The mayor got behind the project and bought the land to the west between the museum and the water. To the east the building lifts the horizon above the adjacent buildings. The result is this great public space that becomes a fifth elevation that you occupy. Icon So even though this is a relatively small building, it aligns with both near and far elements in the landscape. It’s not unlike how the ancient Greeks would align even the smallest temple structure to a very distant landscape and to the cosmos. SH Exactly. It’s a small building with a big horizon and a big spatial and experiential ambition. Another small building that tries to engage multiple scales, including the very large, is a community library at Queens West [in New York], a development of anonymous condominium towers. It’s situated on the East River directly across from the United Nations where it becomes a cousin of this famous Pepsi Cola sign. Everyone on the east side of Manhattan will see this building even though it is very small. The facade is made of 100 percent recycled aluminium. At night the building will present a glowing view from across the river. From the Queens side, landscape is key as well. We could have accommodated the entire programme on one floor on the site, but we thought we’d make it a presence on the water while giving back most of the site to the city. So you enter in through a garden that leads through a bosque of gingko trees. The building is very thin so you can see through it. The building is shifted on a north-south axis so it doesn’t look at those towers in Queens West, it looks across the city. This is a small garden, but it acts as an interface to the city, a catalyst to open up and interact with the community in ways beyond books. The notion that you enter into it through a public space adds, I think, a positive dimension. It could’ve been done otherwise. The Manhattan views inscribe a cut into the facade and the main movement in the building is along that view. The way you will move through the building cuts an arc right through the facade, giving you a sense of space but also connecting you back to Manhattan. The facade openings also correspond to the different divisions within the programme, between the children’s area, the adult area, and the teen area. Inside, the library also acknowledges another condition, which is that of the digital, which is inevitable. The book has to coexist with it. You can sit along a set of workstations but behind it are books. So you see both the book and the digital at the same time, there’s no segregation as there is at the Seattle Public Library where the lobby is filled only with people on computers. Icon What about the Sifang Art Museum in Nanjing? That’s somewhere in between in terms of scales. What’s going on in that project? SH Nanjing is a very important site. It’s an ancient Chinese city, once the capital, and our building is one of a series of pieces curated by Arata Isozaki in the city. Our building was the head building, the entrance piece. It was our first project in China but it’s only now being completed. Since it’s a museum of art and architecture I was trying to engage perspective, both the notion of Western perspective, with its vanishing points, and the Chinese approach. They knew about vanishing points but continued to produce works with parallel perspective without vanishing points, in part because of the way their drawings were made and displayed on scrolls. The ground plan is really a warped perspectival space that sets up as parallel perspective and you rise up in the lantern section that looks back at the city with a more distant view. The courtyard and its sequence of space are done in parallel perspective so you have a slightly distorted sense of space. As you enter and you come up in the building, you get this sort of middle ground and then, as you arrive at the top, you see the distant view back at the city. So the building is formed not only on its own terms, but also by a history of perspective and distant relationships across the city. Icon If spatial relationships are very important to you, I know you have also been thinking a lot about time and designing for different durations. In The Rise of the Network Society, Manuel Castells points to the waiting room of your DE Shaw trading floor [in New York] as an example of the space of flows, a space in which information and finance flow at will and seemingly outside time. He suggests that on the one hand, the work represents the deep abstraction found in the space of flows, but on the other hand, imbues the world with meaning, thus creating a kind of cultural resistance. SH DE Shaw is still a client of ours. That was the first hedge fund to have a trading floor that would operate over 24 hours, across multiple time zones. But if there’s a certain experience of time in which everything is speeded up and we’re working in all these time zones at once, what’s interesting to me about architecture is how it has the possibility of engaging with time differently. Architecture has all these other levels of time. There’s the duration of the building itself. I’ve built long enough that I know the duration of say, the Kiasma Museum in Helsinki. Materials acquire a patina over time. But light and the seasons are registered by a building. A structure captures a certain sense of light and that light changes over time. And there’s also the experience of moving through buildings, sequences that you pass through. The building becomes a kind of clock or organism that measures time. I set out to build for the longer term, to build robust space with natural light and good geometry that can be used for different functions and be used in different ways. That’s an argument for architects designing within a longer time span. Some university campuses now require building for a 100-year timespan and there’s a good reason for it. We can think of the long duration as part of an ecological argument. Fifty percent of waste is construction debris so if you design your buildings to last, you are greatly reducing the amount of waste you produce. Even temporary architecture can be affected by the need to take into account duration. Vito Acconci and I thought the Storefront for Art and Architecture [in New York] would last six months but because the idea was so strong – this notion of hinged space, where the outside becomes the inside and the street is engaged – it was rebuilt in a more permanent way. So even if you want to make something just for event, it may endure. Icon How do you react to knowing that the city will continue to change around your building? SH That’s a positive thing. If a building has good bones, good space and a positive urban presence it can be reprogrammed. Completely different and unforeseen events can occur. That becomes part of the life of the building. “Life is always right,” Le Corbusier said.

|

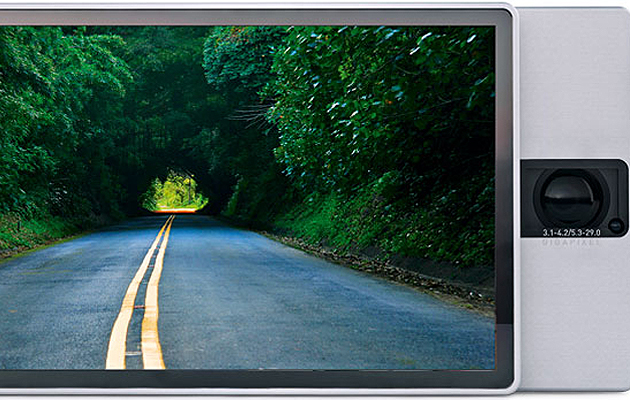

Image Steven Holl

Words Kazys Varnelis |

|

|

||